Federal Court of Australia

The Agency Group Australia Ltd v H.A.S. Real Estate Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 203

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The appeal be dismissed.

2. The appellants pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

THE COURT:

Introduction

1 The appellants appeal from Order 1 made on 17 May 2023, and Orders 1, 2, and 3 made on 15 June 2023, in a proceeding in which the primary judge found that the respondent had not infringed the second appellant’s registered trade marks, had not engaged in passing off, and had not engaged in misleading or deceptive conduct, or made false or misleading representations in contravention of the Australian Consumer Law (Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth): Agency Group Australia Ltd v H.A.S. Real Estate Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 482; 174 IPR 153 (J).

2 Order 1 made on 17 May 2023 is an order dismissing the proceeding. Orders 1, 2, and 3 made on 15 June 2023 are orders providing for the costs of the proceeding.

3 The appellants’ appeal focuses on the primary judge’s finding that the respondent had not infringed one of the registered trade marks—specifically, the mark referred to below as the AGENCY Mark.

4 The success of the appellants’ appeal on the orders for costs made by the primary judge is dependent on the success of the appeal itself. In other words, the appellants contend that the primary judge should have found that the respondent had infringed the AGENCY Mark and granted relief accordingly, including (it would seem) an order for costs of the proceeding below, even though the appellants failed on the other causes of action on which they relied.

5 We are not persuaded that the primary judge erred in finding that the respondent had not infringed the AGENCY Mark marks. For this reason, the appeal fails, including the appellants’ appeal on the question of costs.

Background

6 The second appellant, Ausnet Real Estate Services Pty Ltd, and the third appellant, The Agency Sales NSW Pty Ltd, are wholly-owned subsidiaries of the first appellant, The Agency Group Australia Limited (The Agency Group).

7 The Agency Group carries on a real estate business providing services in residential sales, project marketing, property management, and finance to customers across Australia. It currently has over 400 agents Australia-wide, including 26 offices in New South Wales operating from 21 physical locations, with the Northern Beaches region of Sydney specifically serviced by offices in Manly and Neutral Bay.

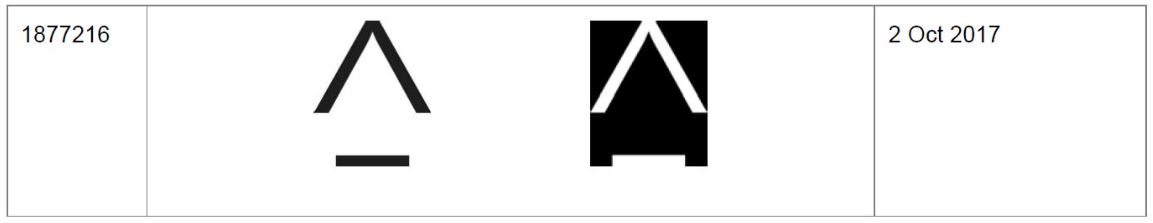

8 The second appellant is the owner of the following registered trade marks, which are registered in relation to a range of real estate services in Class 36 (designated services):

9 The primary judge referred to Trade Mark 1836914 as the AGENCY Mark and to Trade Mark 1877216 as the Logo Mark.

10 Since about 2017, The Agency Group has promoted its business using the registered marks.

11 The respondent also carries on a real estate business, which is located in Dee Why, in the Northern Beaches region of Sydney. This business commenced operation in March 2023 under the name THE NORTH AGENCY. In the course of setting up that business, the respondent’s directors Mr Aldren and Mr Sila (who were the second and third respondents in the proceeding below) engaged a firm called UrbanX to design logos for the new business. The directors decided upon, and adopted, a particular stylised rendering of the name of THE NORTH AGENCY and a logo comprising the stylised letter N and a degree symbol (referred to as the N Logo). Examples of each are shown in the following screenshot from the respondent’s website:

12 The rendering of THE NORTH AGENCY in the above example is not the only way in which those words are presented by the respondent as part of its brand.

13 In the proceeding below, the appellants alleged that the respondent’s use of THE NORTH AGENCY in its real estate business infringed the AGENCY Mark, and that its use of the N Logo infringed the Logo Mark.

14 The primary judge was satisfied that the respondent had used THE NORTH AGENCY and the N Logo as trade marks. He was not satisfied, however, that THE NORTH AGENCY, when used as a trade mark, is deceptively similar to the AGENCY Mark or that the N Logo is deceptively similar to the Logo Mark. For this reason, the case brought by the appellants for infringement under s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (the Act) was not established.

The primary judge’s reasons

15 The primary judge commenced his consideration of the question of deceptive similarity by referring to the principles recently stated by the High Court in Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd [2023] HCA 8; 408 ALR 195. There is no dispute about those principles which, as the primary judge observed, are well-established. It is not necessary for us to rehearse them in these reasons.

16 With respect to the AGENCY Mark and the respondent’s use of THE NORTH AGENCY as a trade mark, the primary judge reasoned that the insertion of the word “NORTH” in THE NORTH AGENCY was a substantial feature which differentiated THE NORTH AGENCY from the AGENCY Mark. He found that this word would remain in the minds of ordinary consumers with imperfect recollection. Indeed, his Honour regarded use of the word “NORTH” as “a striking aspect of the mark which points strongly against any real likelihood of confusion”, and considered that the inclusion of this word in the respondent’s brand name was alone sufficient to undermine the appellants’ argument for infringement.

17 The primary judge took into account the aural impression of THE NORTH AGENCY and was satisfied that aural use of the word “NORTH” in this combination was just as striking when spoken as it was in its written form. Even so, his Honour did not regard aural resemblance as being particularly significant in the present case given the evidence before him as to the manner in which real estate services are typically acquired.

18 In undertaking his analysis, the primary judge stressed the importance of considering “the whole of the marks and all of their elements”. In this connection, his Honour had regard to the principle discussed in Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 1380; 275 ALR 526 (Optical 88) at [100] – [111]; Australian Meat Group Pty Ltd v JBS Australia Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 207; 268 FCR 623 (Australian Meat Group) at [78]; and Crazy Ron’s Communications Pty Ltd v Mobileworld Communications Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 196; 61 IPR 212 (Crazy Ron’s) at [100] that, in the case of a composite mark, all the elements of the mark must be considered in their context including the size, prominence, and the stylisation of words and devices, and the relationship of all these elements to each other.

19 In applying this principle in the present case, the primary judge stressed that the AGENCY Mark is not a word mark but a composite mark in which the stylised “A” cannot be ignored. It is an element of the composite mark which the ordinary consumer would not fail to recall. His Honour noted that this presentation of the letter “A” represents a stylised roof or house device.

20 His Honour also said that it was relevant to take into account that the words “THE AGENCY” on their own have a strongly descriptive element in referring to the nature of the real estate business. His Honour said that the ordinary consumer would expect the word “AGENCY” to be commonly used in the names of real estate businesses in Australia.

21 His Honour noted that both the word “AGENCY” and a stylised roof or house device representing the letter “A” are commonly used in business names and marks in the real estate industry, which made it even less likely that consumers would be confused by any resemblance between the AGENCY Mark and THE NORTH AGENCY when used as a trade mark. In this connection, the primary judge referred to six other real estate agencies that were using the word “AGENCY” in their brand name and five real estate agencies that were using a roof-shaped device either in place of the letter “A” or beside their brand name.

22 Further, the primary judge considered the importance of context in analysing trade mark use. His Honour said that the buying, selling, and leasing of real property are among the most important transactions which ordinary consumers engage in during their lives. He reasoned that one would expect a heightened sense of awareness and concentration amongst consumers in that context, compared to the degree of concentration and focus which would ordinarily be expected in more mundane, everyday transactions, such as the purchase of grocery or ordinary household items. He found that this heightened awareness and concentration of consumers would be present at the early stages of a real estate transaction.

23 The primary judge was not persuaded by the appellants’ submission that an ordinary consumer might wonder whether the services provided by THE NORTH AGENCY might be a commercial extension, franchise or sub-brand of the business identified by the AGENCY Mark. His Honour concluded that there was not a real risk of confusion, having regard to the reasons he had already expressed. His Honour also noted that use of the definite article “THE” in the AGENCY Mark conveyed a claim to uniqueness among real estate agencies generally. On the other hand, the insertion of the word “NORTH” in THE NORTH AGENCY diminished any claim to uniqueness conveyed by the AGENCY Mark and that this would be apparent to consumers.

The application to adduce new evidence

24 The respondent seeks leave pursuant to s 27 of the Federal Court of Australia Act 1976 (Cth) (the Federal Court Act) to rely on evidence not adduced in the proceeding below. It does so on the basis that the evidence was not available to be tendered in that proceeding. The evidence is a submission made by the second appellant to the Registrar of Trade Marks (the Registrar) at the time of prosecuting the application for the AGENCY Mark. That submission advanced the particular form of the AGENCY Mark—and especially the stylised “A”— as a reason why the application for registration of the mark should be accepted under s 33 of the Act.

25 The respondent argues that the second appellant’s submission only became available to it as a result of the response by IP Australia on 29 May 2023 to a Freedom of Information (FOI) request made by it on 28 March 2023.

26 In this connection, the proceeding below was commenced on 21 March 2023. The appellants applied for interlocutory relief. However, the primary judge was able to offer the parties an expedited final hearing, which both parties agreed to accept. On 14 April 2023, the proceeding was set down for a final hearing on 10 and 11 May 2023. The hearing proceeded on those dates and the primary judge gave judgment on 17 May 2023 before the response to the FOI request was received.

27 In Sobey v Nicol and Davies, in the Matter of Guiseppe Antonio Mercorella [2007] FCAFC 136; 245 ALR 389 the Full Court said (at [68] – [72]):

68 Section 27 of the Federal Court Act authorises the Court in an appeal to receive further evidence by affidavit. The circumstances in which the Court should exercise its discretion under s 27 to receive further evidence have been considered by the High Court in CDJ v VAJ (1998) 197 CLR 172 (in the context of the similarly worded s 93A(2) of the Family Law Act 1975 (Cth)) and by the Full Court of this Court in Cottrell v Wilcox [2002] FCAFC 53 at [20]-[24]; Gao v Official Trustee in Bankruptcy [2003] FCAFC 84 at [23]; Freeman v National Australia Bank Limited (2003) 2 ABC (NS) 32 at 48-50; [2003] FCAFC 200 at [68]-[74] and Li Pei Ye v Crown Limited [2004] FCAFC 8 at [157]-[161] as well as in Williams v Grant ….

69 The above authorities reveal that the circumstances in which further evidence may be received in this Court on appeal are not limited by the principles laid down in authorities such as Wollongong Corporation v Cowan (1955) 93 CLR 435 which concern common law procedures. The proper limits of the discretion vested in the Court by s 27 are to be determined as a matter of statutory construction. As the Federal Court Act is silent as to the factors which govern its exercise, the discretion is confined only by the subject matter with which the Act is concerned. It should not be understood to be subject to implications or limitations not found in the words used by the legislature. It is a discretion to be exercised in the context of an appeal by way of rehearing. On appeal this Court is required to determine the rights of the parties upon the facts and in accordance with the law as it exists at the time of hearing the appeal.

70 A critical factor will be the subject matter of the proceeding with which the appeal is concerned. As the High Court observed in CDJ v VAJ the Court will more readily admit further evidence where the rights of third parties, such as children are at stake.

71 The discretion to receive further evidence must be exercised judicially, consistently with proper judicial process and in the interests of justice. It is highly unlikely that the legislature intended that s 27 should be construed in such a way as to obliterate the distinction between original and appellate jurisdiction.

72 The proper role of an appellate court under s 25 of the Federal Court Act has been considered on a number of occasions in recent years including in Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd & Anor (2001) 117 FCR 424 and Poulet Frais Pty Ltd v The Silver Fox Company Pty Ltd (2005) 220 ALR 211 at [45]; it is ordinarily to correct error. Nothing in CDJ v VAJ was, in our view, intended to minimise the force of the observation of Gibbs CJ and Wilson, Brennan and Dawson JJ in Coulton v Holcombe (1986) 162 CLR 1 at 7 that:

It is fundamental to the due administration of justice that the substantial issues between the parties are ordinarily settled at the trial. If it were not so the main arena for the settlement of disputes would move from the court of first instance to the appellate court, tending to reduce the proceedings in the former court to little more than a preliminary skirmish.

28 Notwithstanding the generality of these observations, the Full Court in August v Commissioner of Taxation [2013] FCAFC 85 noted (at [116]) the importance of considering in such an application (a) whether the evidence could have been called in the proceeding from which the appeal is brought and, if it could have been, why it was not, and (b) the extent to which the further evidence had the ability to affect the result of that proceeding: see also Northern Land Council v Quall (No 3) [2021] FCAFC 2 at [15] – [16]; BVZ21 v Commonwealth of Australia [2022] FCAFC 122 at [12].

29 At the time the parties agreed to an expedited final hearing, when the appellants were pressing for interlocutory relief, it must have been apparent to the respondent that a response to its FOI request might not be forthcoming before the final hearing. From the respondent’s perspective, the final hearing could only have been conducted on the basis that it would defend the claims made against it regardless of whether it had received a response to the request. This circumstance is reason enough to deny the respondent’s application to adduce the second appellant’s submission to the Registrar in this appeal.

30 There are, however, other impediments to allowing its application. For one thing, other means were available to the respondent to obtain a copy of the second appellant’s submission to the Registrar for the purposes of the final hearing—most notably, by issuing a notice to produce on the second appellant.

31 Further, the second appellants’ submission to the Registrar is simply that. Although it advances a different case to the one now made by the appellants on appeal, it adds nothing of substance to the material that was already before the primary judge. Further, having regard to the primary judge’s findings, the second appellant’s submission is not material that could have led to a different outcome of the final hearing.

32 For these reasons, we reject the application to adduce further evidence.

The grounds of appeal

33 As we have noted, this appeal focuses on the primary judge’s finding that the respondent had not infringed the AGENCY Mark by reason of its use of THE NORTH AGENCY as a trade mark.

34 Ground 1 alleges error on the part of the primary judge in relation to J[69], [71], [72], [74], [75] and [76] of his Honour’s reasons for judgment. This ground is concerned solely with his Honour’s application of the well-established principles relating to deceptive similarity to which we have alluded, and involves various aspects of his Honour’s reasoning.

35 Ground 2 alleges that, by reason of the errors referred to in Ground 1, the primary judge’s “discretion” miscarried in finding that infringement under s 120(1) of the Act was not established.

36 Ground 3 of the appeal alleges that, on a proper application of the established principles on deceptive similarity under s 120(1) of the Act, the primary judge should have found that (in substance) THE NORTH AGENCY is deceptively similar to the AGENCY Mark for the reason that there is a real likelihood that consumers for real estate services “are at a risk of wondering, or being perplexed or mixed up, as to whether it might not be the case that real estate services provided by THE NORTH AGENCY might be a commercial extension, franchise or sub- brand” of the AGENCY Mark.

The appellants’ submissions

37 The appellants contend that the decision below is attended by six errors of principle. These alleged errors are captured within the various subparagraphs of Ground 1 of the appeal. Ground 1(e) is not pressed.

38 First, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred by “effectively attributing” to the notional consumer a “perfect photographic recollection” of the AGENCY Mark (the first error of principle): Ground 1(d).

39 This alleged error concerns that part of the primary judge’s analysis we have summarised at [16] – [18] above. The appellants submit that the primary judge failed to consider the possibility that at least a number of persons might not share his Honour’s specific perception of the idea conveyed by the AGENCY Mark.

40 In this connection, the appellants contrast the relative simplicity of the AGENCY Mark with the “significant visual details” of the marks in suit in Optical 88, Australian Meat Group, and Crazy Ron’s. The appellants submit that, unlike the device marks in those cases:

the AGENCY Mark comprises the words “THE AGENCY” rendered in “a plain script”, with the mere relocation of the horizontal stroke of the letter “A” to a position beneath the letter. The appellants submit that the perception of the letter “A” in the AGENCY Mark as a house (which the appellants say is a perception that is “abstract and subtle”) is open to different views. Consumers who do not have that perception will not have the mnemonic hook to remember that feature perfectly.

41 Secondly, the appellants contend that, by adverting to whether the second appellant would have an “unwarranted monopoly” if rival businesses were unable to use the definite article “THE” and the word “AGENCY” in their business names, the primary judge did not focus on the question whether there is a real risk that a number of consumers with imperfect recollection of the AGENCY Mark would confuse that mark with THE NORTH AGENCY (the second error of principle): Ground 1(c).

42 This alleged error also concerns that part of the primary judge’s analysis we have summarised at [16] – [18] above. It focuses on a comment made by the primary judge at J[72] when observing that the words “THE AGENCY” on their own have a strongly descriptive element in referring to the nature of a real estate business, and that the ordinary consumer would expect the word “AGENCY” to be commonly used in the names of real estate businesses in Australia. The appellants submit that the primary judge proceeded on the basis that the appellants were propounding a case (which, in fact, they were not propounding) that no other businesses could use the definite article “THE” and the word “AGENCY” in their business names.

43 Thirdly, the appellants contend that the primary judge discounted the words “THE AGENCY” and the stylised “A” in the AGENCY Mark as being descriptive and common in the trade (the third error of principle): Ground 1(c).

44 This alleged error is a criticism of the primary judge’s analysis we have summarised at [19] – [21] above. According to the appellants, the primary judge “stripped” the registered mark of its features and thereby “severely undermined” the statutory monopoly granted to the second appellant.

45 The appellants submit that, even so, his Honour’s approach should have led him to appreciate that the likelihood of confusion was increased because the only element of the AGENCY Mark not present in THE NORTH AGENCY is the stylised “A”.

46 As we have noted at [21] above, the primary judge referred to six other real estate agencies that were using the word “AGENCY” in their brand names. The appellants submit that there are numerous points of difference in the presentation of the names of these agencies, which should have demonstrated to his Honour the similarity between the AGENCY Mark and THE NORTH AGENCY.

47 Fourthly, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred in identifying the word “NORTH” as the distinctive feature of THE NORTH AGENCY (the fourth error of principle): Ground 1(a). The appellants contend that, by so finding, the primary judge excluded the possibility that at least a number of other persons might perceive that mark “as a combined whole” without particular emphasis on any single word. This alleged error concerns that part of the primary judge’s analysis we have summarised at [16] above.

48 In this connection, the appellants submit that the word “NORTH” simply functions as an adjectival identifier that the respondent’s business has a northern location. Borrowing from the Full Court’s observations in Pham Global Pty Ltd v Insight Clinical Imaging Pty Ltd [2017] FCAFC 83; 251 FCR 379 at [52], they submit that a mark’s essential features or “dominant cognitive clues” are unlikely to be found in mere descriptive elements. They submit that the primary judge should have concluded that there is no particular part of THE NORTH AGENCY that is distinctive or more distinctive than any other part of the mark. They submit that the:

… distinctive feature of the mark is the whole combined phrase THE NORTH AGENCY. That whole phrase is what ought to have been compared to notional consumers’ imperfect recollect of [the AGENCY Mark].

49 The appellants submit that “the inherent premise of the primary judge’s analysis” is that THE NORTH AGENCY is “only open to be perceived in one way” and that “all consumers would perceive NORTH as ‘the distinctive feature’ of that mark”. According to the appellants, the primary judge acted on his own perception that the word “NORTH” is “the distinctive feature” and failed to consider whether at least “a number” of other persons might perceive THE NORTH AGENCY differently (i.e., reading THE NORTH AGENCY as a combined whole without particular emphasis on any single word).

50 Fifthly, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred by excluding any risk of confusion arising from the aural use of the two marks (the fifth error of principle): Ground 1(b). According to the appellants, the primary judge thereby disregarded the aural resemblance of the two marks despite s 7(2) of the Act (which provides that any aural representation of a trade mark is, for the purposes of the Act, a use of the trade mark) as well as the evidence of common aural use of such marks in the provision of real estate services.

51 The appellants contend that his Honour failed to consider and deal with the respondent’s evidence that the conduct of its business involved the use of telephones for “cold calling” and “prospecting” for new listings, and for following up inquiries from potential buyers, during which agents introduced themselves and the name of their business aurally. The appellants submit that the agreed evidence from both parties—that “word of mouth” is an important means of attracting customers—required his Honour to grapple properly with the risk of confusion arising from aural use of the marks.

52 Sixthly, the appellants contend that the primary judge erred by rejecting any risk that an ordinary consumer might wonder whether the services provided by THE NORTH AGENCY might be a commercial extension, franchise or sub-brand of the owner of the AGENCY Mark (the sixth error of principle): Ground 1(f). The appellants contend that the primary judge based his assessment of the two marks on “a single idiosyncratic perception” of them.

53 The appellants advance a further argument. They submit that real estate in the Northern Beaches region is “particularly exclusive and sought-after” and that the respondent advertises its properties accordingly. According to the appellants, the respondent’s use of THE NORTH AGENCY is therefore at least as likely to maintain, rather than dilute, the “hubris” of the AGENCY Mark.

Analysis

Preliminary comments

54 We commence our consideration of the appellants’ submissions by making some preliminary comments about the task imposed by s 120(1) of the Act and the manner in which the primary judge carried out that task.

55 First, understanding the scope of the registered mark, as a sign, is fundamental to the infringement question. Here, the AGENCY Mark is not simply the words “THE AGENCY”. Rather, it is those words represented in a particular stylised form.

56 Therefore, the exclusive right to use the AGENCY Mark in respect of the designated services that is conferred on the second appellant, as owner of the mark, by s 20 of the Act, is not the right to use the words “THE AGENCY”; it is the exclusive right to use those words represented in the particular stylised form of the mark as registered. To ignore the significance of the particular stylised form of the AGENCY Mark would be to extend its scope well beyond the monopoly that has been granted to the second appellant by registration of the mark under the Act: Australian Meat Group at [78]. This is an important matter to bear in mind, which was recognised by the primary judge.

57 Secondly, the infringement question posed by s 120(1) of the Act is answered objectively by reference to a construct. As described by the High Court in Self Care at [28]:

[28] The question to be asked under s 120(1) is artificial — it is an objective question based on a construct. The focus is upon the effect or impression produced on the mind of potential customers. The buyer posited by the test is notional (or hypothetical), although having characteristics of an actual group of people. The notional buyer is understood by reference to the nature and kind of customer who would be likely to buy the goods covered by the registration. However, the notional buyer is a person with no knowledge about any actual use of the registered mark, the actual business of the owner of the registered mark, the goods the owner produces, any acquired distinctiveness arising from the use of the mark prior to filing or, as will be seen, any reputation associated with the registered mark.

(Footnotes omitted.)

58 Although the High Court described this construct with reference to the buyer of goods, their Honours’ description holds good with respect to an acquirer of services in relation to a mark that is registered for services.

59 Thirdly, insofar as the infringement question concerns whether an alleged infringer has used a mark that is deceptively similar to the registered mark, the construct to which the High Court referred in Self Care proceeds on the basis that notional acquirers of the goods or services have knowledge of the registered mark. As the High Court noted at [29]:

[29] The issue is not abstract similarity, but deceptive similarity. The marks are not to be looked at side by side. Instead, the notional buyer’s imperfect recollection of the registered mark lies at the centre of the test for deceptive similarity. The test assumes that the notional buyer has an imperfect recollection of the mark as registered. The notional buyer is assumed to have seen the registered mark used in relation to the full range of goods to which the registration extends. The correct approach is to compare the impression (allowing for imperfect recollection) that the notional buyer would have of the registered mark (as notionally used on all of the goods covered by the registration), with the impression that the notional buyer would have of the alleged infringer’s mark (as actually used). As has been explained by the Full Federal Court, “[t]hat degree of artificiality can be justified on the ground that it is necessary in order to provide protection to the proprietor’s statutory monopoly to its full extent”.

(Footnotes omitted.)

60 Thus, consideration of the question of deceptive similarity proceeds from a premise that is hypothetical rather than actual: Optical 88 at [97]. But, importantly, the hypothesis is knowledge of the mark as registered, even though in undertaking the analysis of deceptive similarity allowance must be made for the imperfect recollection of that mark.

61 This underlines the importance of the first matter to which we have referred—the particular form of the AGENCY Mark. In the present case, the hypothesis is that the intending acquirers of the designated services know, but may have an imperfect recollection of, the particular stylised form of the AGENCY Mark, not just knowledge of, and an imperfect recollection of, the words “THE AGENCY”.

62 Fourthly, the comparison of trade marks for the purpose of considering whether one mark is deceptively similar to another mark is a process of judicial estimation. Minds may well differ as to the outcome of such a process, and in the evaluative findings that are steps along the way to reaching that outcome. Where, on appeal, they do, the fact of difference does not, alone, warrant appellate intervention; nor does the fact that differences can be posited by way of argument. The threshold for appellate intervention is the demonstration of error in the outcome or in the carrying out of the evaluation: Branir Pty Ltd v Owston Nominees (No 2) Pty Ltd [2001] FCA 1833; 117 FCR 424 at [22] – [25]; Christian v Société Des Produits Nestlé SA (No 2) [2015] FCAFC 153; 327 ALR 630 at [123]; Aldi Foods Pty Ltd v Moroccanoil Israel Ltd [2018] FCAFC 93; 261 FCR 301 at [4] – [8] (Allsop CJ), [45] – [53] (Perram J); Combe International Ltd v Dr August Wolff GmbH & Co KG Arzneimittel [2021] FCAFC 8; 157 IPR 230 at [12].

63 An appellate court should give due weight and respect to a primary judge’s evaluative assessments, and exercise caution in reversing such assessments. However, if error is demonstrated, and the appellate court is of the view that an erroneous conclusion has followed, the court should not shirk from correcting that error and reaching its own view: Energy Beverages LLC v Cantarella Bros Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 44; 407 ALR 473 at [158] – [160]; Henley Constructions Pty Ltd v Henley Arch Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 62; 297 FCR 353 at [150] – [151].

64 But, the task of the appellate court is not simply to carry out afresh the evaluative task that the primary judge carried out with a view to supplanting the primary judge’s findings with its own, should it happen to come to a different view: Swancom Pty Ltd v The Jazz Corner Hotel Pty Ltd [2022] FCAFC 157; 407 ALR 93 at [102].

65 Fifthly, in the present case, the primary judge reached his conclusion that the marks used by the respondent were not deceptively similar to the AGENCY Mark by having regard to a range of considerations, not just one consideration. His Honour discussed and explained these considerations at J[69] – [76]. Importantly, it was the combination of these considerations that led to his Honour’s conclusion, although it is clear that his Honour assessed some matters to be more significant than others in his evaluation.

66 Sixthly, a consistent theme in the appellants’ submissions is the contention that, while the primary judge had a view about what the AGENCY Mark conveyed to the notional consumer, he failed to consider that his view was, it seems, no more than an idiosyncratic perception that might not be shared by others.

67 Based on the contention that there is reason to think that others would not share the primary judge’s perception or impression of the two marks, the appellants then developed an argument that, by not taking into account that asserted fact, his Honour failed to apply the standard articulated in Southern Cross Refrigerating Co v Toowoomba Foundry Pty Ltd (1954) 91 CLR 592 at 608, namely that, in order to establish trade mark confusion, it is sufficient “that a number of persons will be caused to wonder whether it might not be the case that the two products come from the same source” (emphasis added): see also Self Care at [32]. Here, the appellants contend that, for various reasons, there would be a number of persons who might be caused to wonder.

68 On proper analysis, the appellants’ argument is no more than this: (a) because, in their contention, a number of persons—“some people”—would not share his Honour’s perception or impression of the two marks, trade mark confusion is inevitably present; and (b) his Honour should have recognised that fact and given effect to it by finding that THE NORTH AGENCY is deceptively similar to the AGENCY Mark, even though that was not his Honour’s objective assessment.

69 This argument is deployed by the appellants to criticise a number of steps in the primary judge’s analysis on deceptive similarity. We reject it.

70 As we have stressed, the task that confronted the primary judge is one of judicial estimation—a process in which minds might well differ as to both the outcome, and the evaluative findings that are steps along the way to reaching that outcome. One aspect of that process on which minds may well differ is “the effect or impression produced on the mind of potential customers” of the marks in suit: Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v F.S. Walton & Co Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 641 at 658; Self Care at [28].

71 Given that minds may well differ on that matter, it cannot be a criticism—and it certainly cannot be a demonstration of appealable error—to point to the possibility that others might have a perception or impression of the marks in suit that is different to the primary judge’s perception or impression, and then argue that the primary judge erred by not giving effect to that possibility.

72 The primary judge’s task was to carry out the objective inquiry described in Self Care at [26] – [33]. Having carried out that inquiry, it was then for his Honour to give effect to his findings by arriving at a conclusion on the ultimate question: as a trade mark used in relation to the designated services, is THE NORTH AGENCY deceptively similar to the AGENCY Mark?

The alleged errors of principle

73 We are not persuaded that the appellants have demonstrated that the primary judge erred in carrying out his comparison of the AGENCY Mark and THE NORTH AGENCY as trade marks and in reaching his conclusion that THE NORTH AGENCY, as a trade mark, is not deceptively similar to the AGENCY Mark.

74 As to the first error of principle ([38] – [40] above), we do not accept that the primary judge attributed to the notional consumer a “perfect photographic recollection” of the AGENCY Mark.

75 First, the primary judge was clearly cognisant of the doctrine of imperfect recollection and the role it plays in determining the question of deceptive similarity. His Honour referred to the doctrine twice at J[55] in his summary of the principles to be taken from Self Care and specifically referred to the doctrine again at J[69] when commencing his analysis of the two marks, particularly in discussing the significance of the presence of the word “NORTH” in THE NORTH AGENCY and the absence of that word in the AGENCY Mark itself (a matter specifically raised in Ground 1(a), to which we will return).

76 Secondly, we do not accept that the primary judge credited the notional consumer with a “perfect photographic recollection” of the AGENCY Mark when discussing, at J[72], the significance of the stylised representation of “A” in that mark.

77 The appellants submit that, in the AGENCY Mark, the words “THE AGENCY” are rendered in “plain script” with the horizontal stroke of the letter “A” relocated to a position beneath the letter.

78 It is not entirely correct to speak of the words of the mark being rendered in “plain script”. A particular font is used. It is correct to say, however, that a particular stylised rendering of the letter “A” is adopted. It is this rendering that sets the letter “A” apart from the other letters of the word elements of the mark.

79 At the final hearing, the appellants adduced evidence from Mr Jensen, the Executive Chairman and Chief Operating Officer of The Agency Group. Amongst other topics, Mr Jensen gave evidence about the development of the AGENCY Mark. He referred to the engagement of a firm called Houston Group to develop the brand for The Agency Group’s business. The material produced by Mr Jensen included the following explanation by Houston Group:

The modern and sophisticated identity was inspired by a simple but powerful brand proposition; brands don’t sell houses, people do. We developed a minimalist mark representing both a home and the bringing together of the industry’s best under one roof. The colour palette is sophisticated with neutral greys accented by a bright crimson red. The typeface is strong, modern and spatially profound, commanding attention in a cluttered market place.

80 There can be little doubt that, in evidence, the appellants were propounding that the AGENCY Mark conveys the idea of a house. Realistically, this impression of the mark could only be conveyed by the stylised “A”.

81 However, it appears that in submissions before the primary judge, the appellants turned a blind eye to this evidence, placing significance only on the words of the mark, not its specific rendering. The primary judge summarised the appellants’ submissions as follows:

64 In the application of those principles to the present case, the applicants made the following submissions. First, the applicants submitted that the impression or recollection to be carried away and retained by the notional consumer with an imperfect recollection of the AGENCY Mark is likely to be of its constituent words. Aurally, those constituent words make up the whole of the mark. Visually, the obvious function of the logo, being the stylised “A” element of the word AGENCY, is as the letter “A”. Reasonable and ordinary consumers, it is submitted, are highly unlikely to perceive and remember the mark as an unpronounceable device followed by the letters GENCY. The stylised “A” element is given no relevant prominence amongst the other letters, its size, font and vertical position are uniform and its horizontal position accords with the correct spelling of the word. The only difference in its stylisation is that the horizontal stroke of the letter “A” has been lowered from the middle to beneath the letter.

82 The appellants adopt the same approach in this appeal. They focus on the words of the AGENCY Mark, not its rendering as a registered mark. As we have noted at [40] above, they even appear to question the primary judge’s apparent acceptance of their own evidence that the stylised “A” conveys the idea of a house.

83 At J[72], and earlier at J[62], the primary judge referred to the Full Court’s caution in Australian Meat Group at [78] that, where the registered mark is a composite mark consisting of a number of elements, all its elements must be considered in undertaking a trade mark comparison. In that case, the registered mark was a composite mark which included a device and letters:

78 We are also of the view that the AMG word mark is not deceptively similar to the AMH device mark. What the two marks have in common is two out of three letters of an acronym. However, this is not sufficient to treat the AMG word mark as deceptively similar to the AMH device mark. First, the AMH device mark is a composite mark. As we have previously emphasised, it is not simply the letters “AMH”. Its other elements, in combination, cannot be ignored. To consider the mark otherwise would be to extend its scope well beyond the monopoly that has been granted to the respondent by registration. Secondly, as a matter of impression, the acronyms are different and distinguishable, not only visually but also by verbal description as initialisms. In stating this, we take into account the level of discernment which his Honour found to be present in the transactions in which these marks are used. Thirdly, the primary judge’s contrary conclusion was, once again, grounded on the substantial reputation he found to exist in the AMH acronym. To import this consideration into the analysis to undertake an erroneous comparison for the purposes of s 120(1) of the Act.

84 Relying on that caution, the primary judge (at J[72]) reasoned that all the elements of the two marks must be considered in the present case:

72 … That includes the use of the stylised “A” conveying the idea of a house, which, in my view the ordinary consumer would not fail to recall. The AGENCY Mark is not a word mark, and the stylised “A” cannot be ignored in the comparison, as this Court made clear in Optical 88, Australian Meat Group and Crazy Ron’s. …

85 The appellants submit that, in this part of his reasons, the primary judge was saying that the ordinary consumer would not fail to recall: (a) the stylised “A” ; and (b) that the stylised “A” conveys (to the consumer) the idea of a house. We do not think that this is the correct reading of this part of his Honour’s reasons. The critical point in this part of his Honour’s reasons is that the ordinary consumer would not fail to recall the stylised “A”. His Honour’s reference to “conveying the idea of a house” appears to be no more than an incidental observation. His Honour did not make an antecedent finding that, in fact, the stylised “A” does convey, to the ordinary consumer, the idea of a house.

86 The primary judge did not err in attributing significance to the stylised “A” in the AGENCY Mark and in finding that the ordinary consumer would not fail to recall that element of the mark. His Honour’s analysis in this part of his reasons was entirely in accord with orthodox principles of trade mark comparison, bearing in mind that the AGENCY Mark is a composite mark. In arriving at that finding, the primary judge did not attribute to the ordinary consumer the standard of “perfect photographic recollection”. Indeed, it seems to us that the simplicity of the AGENCY Mark on which the appellants rely is reason to think that the ordinary consumer’s capacity to recall that mark is likely greater than his or her capacity to recall the more detailed device elements of the marks reproduced at [40] above.

87 Further, if, contrary to our view, the primary judge made a finding that the ordinary consumer would understand the stylised “A” as conveying the idea of a house and that, on that basis, the ordinary consumer would not fail to recall the stylised “A”, his Honour did not err. This finding would be consistent with the appellants’ own evidence as to the impression conveyed by the AGENCY mark—an impression which, before the primary judge, the appellants did not disavow.

88 As to the second error of principle ([41] – [42] above), we do not accept that the primary judge’s reference in J[72] to “an unwarranted monopoly” shows that the primary judge “distracted himself” and was diverted from the task of determining whether, as a trade mark, THE NORTH AGENCY is deceptively similar to the AGENCY Mark.

89 The primary judge’s reference to “an unwarranted monopoly” must be seen in the context of the whole of his Honour’s analysis in J[72]. That analysis considered all the elements of the AGENCY Mark, and the impression of those elements on the ordinary consumer. His Honour’s reference to “an unwarranted monopoly” is really no more than a statement that, if the scope of the registration of the AGENCY Mark extends to the mere use of the words “THE” and “AGENCY” by a rival supplier of the designated services, then this would be “an unwarranted monopoly” because it would exceed the monopoly right created by the scope of the registered mark, properly construed. In other words, the primary judge was doing no more than reflecting on the precise scope of the AGENCY Mark as a composite mark, rather than as a word mark (a broader form of registration).

90 In this connection, we also do not accept that the primary judge misunderstood the case that the appellants were propounding. He was, in fact, analysing that case.

91 The appellants’ contentions in relation to the third error of principle ([43] – [46] above), seem to be somewhat at odds with their contentions in relation to the first error of principle. On the one hand, the appellants play down the significance of the stylised “A” when advancing their first error of principle and, on the other hand, allege that the primary judge erred by “discounting” the significance of the stylised “A” as well as the word elements of the AGENCY Mark in his analysis of that mark.

92 In fact, in J[72], the primary judge did not “discount” the significance of the stylised “A”. As discussed above, the primary judge found that the stylised “A” of the AGENCY Mark could not be ignored and that the ordinary consumer would not fail to recall it. For the purposes of his comparison, this was an element of the AGENCY Mark that was not present in the respondent’s use of THE NORTH AGENCY. It was thus a point of distinction between the two marks to be taken into account in assessing whether they are deceptively similar.

93 However, as we have noted above, in evidence the appellants advanced the stylised “A” in the AGENCY Mark as conveying the idea of a house. In response, the respondent’s solicitor, Ms Kennedy, conducted a number of searches, which included searches of other real estate agencies using a roof-shaped device either in place of the letter “A” or beside the agency’s brand name. As the primary judge recorded at J[74], there were five such real estate agencies.

94 Thus, even though a stylised “A”, conveying the idea of a house, was not used by the respondent in rendering its name THE NORTH AGENCY, other businesses offering the designated services did use a device similar to the stylised “A” of the AGENCY Mark. Therefore, the respondent’s use of THE NORTH AGENCY did not involve use of an element used in the brand names of other suppliers of the designated services, including the appellants by use of the AGENCY Mark.

95 This led the primary judge to conclude that, apart from the differences between THE NORTH AGENCY and the AGENCY Mark (which, at that point in his reasons he had already discussed), these considerations made it even less likely that consumers would be confused by any resemblance between THE NORTH AGENCY and the AGENCY Mark, including any resemblance from use of the word “AGENCY” itself. The primary judge did not err by arriving at that conclusion.

96 Importantly, by analysing the descriptive elements of the AGENCY Mark, including whether those elements were common in the brands of other suppliers of the designated services, the primary judge did not “strip” the AGENCY Mark of its features; still less did the primary judge “undermine” the statutory monopoly granted by registration of the AGENCY Mark, as the appellants contend. The primary judge was doing no more than analysing the AGENCY Mark and determining the scope of its registration. In this process, the primary judge was not ignoring elements of the AGENCY Mark that were common. He was, in fact, relying on an element of the AGENCY Mark that was common in the brands of other suppliers, but not present in the respondent’s use of THE NORTH AGENCY, to further distinguish THE NORTH AGENCY from the AGENCY Mark.

97 The fourth error of principle ([47] – [49] above), is an example of the submission we have rejected at [66] – [72] above. The fourth error of principle is no more than a disagreement with the primary judge’s analysis of the significance of the word “NORTH” in THE NORTH AGENCY and the absence of that element in the AGENCY Mark. The appellants have not demonstrated error in the primary judge’s analysis or finding in this regard.

98 As to the fifth error of principle ([50] – [51] above), we do not accept that the primary judge excluded the risk of confusion arising from the aural use of the two marks.

99 The primary judge specifically addressed aural use at J[70] – [71], finding that the presence of the word “NORTH” in THE NORTH AGENCY is just as striking in its spoken form as it is in its written form. He found that, in its spoken form, the stress that would naturally fall on the word “NORTH” is as least as much as the stress that would fall on the word “AGENCY”.

100 It is important to understand that, by finding that the spoken use of the word “NORTH” is just as striking as its written use, the primary judge was referring to his conclusion at J[69] that the word “NORTH” is “a substantial differentiating feature of the AGENCY Mark which would remain in the minds of ordinary consumers with imperfect recollection” of the AGENCY Mark, and that the addition of the word “NORTH” is “not merely a reference to a geographical location, but also serves to distinguish a competing provider of real estate services”. His Honour considered the word “NORTH” to be a striking aspect of THE NORTH AGENCY “which points strongly against any real likelihood of confusion”.

101 The primary judge accepted at J[71] that “similarities in sound and meaning may play an important part” in comparing two marks: Australian Woollen Mills at 658. However, his Honour did not consider aural resemblance to be a matter of particular significance in the present case, for the reasons he gave. Those reasons show that the primary judge did not ignore the evidence of the spoken use of a real estate agency’s name.

102 In reaching his conclusion that aural resemblance is not a matter of particular significance in the present case, the primary judge was not finding that aural resemblance could be ignored. He simply weighed the significance of aural use in relation to the significance of the visual use of a real estate agency’s name in providing the designated services. We are not persuaded that his Honour erred in giving the aural use of the word “NORTH” the significance he considered it to have in relation to its written use.

103 Importantly, his Honour’s conclusion in that regard did not qualify, and certainly did not undermine, his finding that the aural use of the word “NORTH” in THE NORTH AGENCY entailed the same distinguishing effect as the written use of the word. Thus, if the thrust of the appellants’ submissions is that the primary judge should have given greater significance to the aural use of the word “NORTH” in THE NORTH AGENCY, then giving aural use that significance can only support the primary judge’s ultimate conclusion that THE NORTH AGENCY is not deceptively similar to the AGENCY Mark.

104 We also add this caution about considering the aural use of a mark that consists of ordinary descriptive words represented in a particular stylised form. We do not accept that the aural use of such a mark can be given equal or greater significance than its visual form. If it were otherwise, the boundaries fixed by the visual form of the mark, as registered, would be effectively ignored, thus conferring on the registered owner an unwarranted monopoly in the simple use of descriptive words in relation to the designated goods or services.

105 The sixth error of principle ([52] – [53] above) is a further example of the submission we have rejected at [66] – [72] above. The sixth error of principle is no more than a disagreement with the primary judge’s rejection of the appellants’ allegation that use by the respondent of THE NORTH AGENCY is likely to lead to a particular form of confusion. The appellants have not demonstrated error in the primary judge’s analysis or finding in this regard.

106 The primary judge’s conclusion at J[76] must be considered in light of his Honour’s earlier findings as to how the ordinary consumer would understand the two marks.

107 We do not see error in the primary judge’s reliance on the uniqueness conveyed by the word elements of the AGENCY Mark (“THE AGENCY”), with full recognition being given to the definite article “THE” which imparts that uniqueness. This finding was open to his Honour on the word elements of the AGENCY Mark, as well as on its visual form.

108 It is not apparent to us how the respondent’s business location provides the particular evidentiary support for the business connection for which the appellants contend: see [53] above. It is certainly true that the respondent’s business is located in the Northern Beaches region of Sydney and provides the motivation for the respondent’s adoption of THE NORTH AGENCY mark. The primary judge found that this adoption was in good faith. But the fact of business location says nothing about the existence of the business connection between the respondent’s business and The Agency Group’s business for which the appellants contend.

109 Indeed, the primary judge found that the respondent’s use of the word “NORTH” was a striking aspect of the respondent’s mark which pointed strongly against any real likelihood of confusion. As we have said, the appellants have not demonstrated error in the primary judge’s analysis or finding in that regard.

The notice of contention

110 The respondent has filed a notice of contention raising three grounds. The first ground is no longer relied on. The second and third grounds challenge the primary judge’s finding that the defence under s 122(1)(b) of the Act (relevantly, the use of a sign in good faith to indicate the “kind” or “some other characteristic” of the designated services) was not available to the respondent: J[82] – [85]. Having regard to our rejection of the appellants’ grounds of appeal, it is not necessary for us to consider the notice of contention, and we decline to do so.

Disposition

111 The appeal fails. The appellants should pay the respondent’s costs of the appeal.

I certify that the preceding one hundred and eleven (111) numbered paragraphs are a true copy of the Reasons for Judgment of the Honourable Justices Yates, Markovic and Kennett. |

Associate: