I am standing in the middle of a locker room surrounded by the school football team. My frame is weedy. I have vulnerable knees. My eyes search for an escape, but it’s too late. The chief roughneck among the team, known among our halls as The Fullback, steps forward and breathes aggressively into my face. He has taken issue with what I am wearing.

“What are these pink shorts? Are you a girl or something?” he asks. I deflect the only way I know how – high-voiced sarcasm (“Dear me, are there any rednecks around?”) – and it doesn’t go down well.

“I’m no redneck, you dickwad,” says The Fullback. “I’m a man.”

All at once the football team springs for me and rips off my shorts, landing punches in my ribs, throat and shins. My asthma inhaler and mints fall out of my pockets. A wound opens in my cheek and I begin to bleed. I am alone and reeling. My ribs feel like they might be broken. It is difficult to breathe. My shorts are torn to pieces, and I am in a naked heap on the locker room floor.

“What the heck happened here, Dunne?” asks the PE teacher when he wanders back in from his break.

“Well, sir – I was wearing pink.”

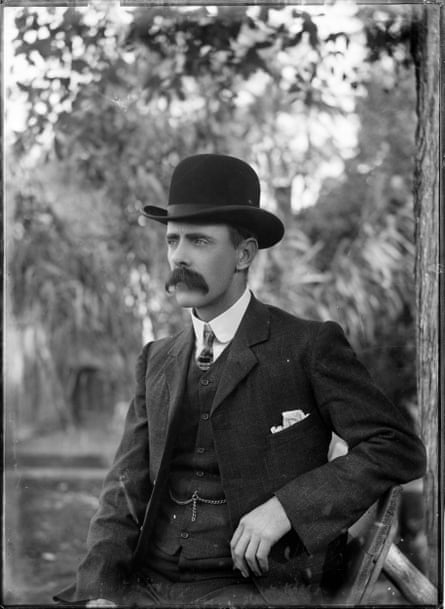

I was reminded of this teenage trauma while visiting Australian Men’s Style, currently showing at the Powerhouse Museum at the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences. The exhibition, which accompanies the major exhibition Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear 1715–2015, features milestones in Australian menswear: wide-brim gentleman’s hats from 1860 made of cabbage tree palm, walking sticks with snake’s heads, tie patterns of violent car crashes, and black waistcoats from the 1980s adorned with medals and jewellery that evoke gay leather culture.

But perhaps most striking is the range of Speedo swimwear, designed by Peter Travis in 1959-60. Known colloquially as budgie-smugglers, they feature loud colours in dizzying stripes and splotches. Prime ministers Bob Hawke and Tony Abbott famously campaigned in them, while lifeguards up and down the coast sport them confidently on hot sand. Such is their status as the nation’s heroic briefs, that Tourism Australia’s managing director John O’Sullivan was recently seen throwing out pairs to a Las Vegas audience as a way of “inviting people to experience the Australian way of life.”

Meeting with Roger Leong, the curator of the exhibition, I ask him about the relationship between men’s fashion and masculinity in Australia, and how it has evolved. It’s of particular interest now in the #MeToo era, where masculinity itself is being renegotiated.

“Throughout history men have always dressed as extravagantly as women,” Leong says. “Sadly, since the 19th century, in what the psychoanalyst John Flügel called the great male renunciation, men have had a lot of beauty beaten out of them. As men abandoned the excesses of aesthetics, their clothing became more rational, practical, and understated. Like the business suit, for example, it’s so very plain. The problem is that when you renounce extravagance in clothes, you often renounce emotional expression too.”

Standing in front of the budgie smugglers, I ask him why they became so popular. They’re not exactly flattering. “If you have a great physique, then it’s a chance to show off your body. That’s why politicians like Tony Abbott probably like them. I mean, he’s got a great body. I think he’s a genuine alpha-male. And wearing them lets him channel sports heroes too.”

But is his idea of masculinity – that aspiration of the “alpha-male” – not a bit outdated? “Definitely. It’s retrograde. He has a very narrow vision,” says Leong.

Tim Winton has recently spoken about this concept of masculinity as part of his publicity tour for The Shepherd’s Hut. “Some [people] do turn into savages,” he says. “And sadly most of those are boys. They’re trained into it. Because of neglect or indulgence.”

It’s a narrow vision of manhood that I recognise from my own childhood in Australia as an effeminate waif fond of dyeing my hair, collecting Hungarian stamps from the 1870s, and quoting Thomas Hardy poems. This might have made me insufferable, but not necessarily a sissy, as I was often called. Why was I less masculine in pink shorts than the roughnecks in their rugby blues?

The answer is that macho culture, or toxic masculinity, was at the core of what we were taught was Australian. To be a man was to be stoic, homophobic, anti-intellectual and enthralled by sport to the point of catatonia. The boys who beat me were never exposed to a nuanced narrative of masculinity, especially one that allowed for a smart-alec stamp collector like me.

Dr Jessica Kean, who teaches gender studies at the University of Sydney, thinks that our masculine myth has its roots in the early days of colonial Australia, when convicts struggled with exile in a forbidding climate. They were thieves, rapists, deviants. They were also poor, uneducated, devalued.

“As a culture we have had a lot of trouble trying to move away from this idea of men as early settlers,” she says. “The problem is that it doesn’t relate to the lived experience of most men now. So what happens in the disconnect is often misogyny, and a macho performance that results in things like domestic violence and suicide.”

A poem that appeared in the early 1800s, attributed variously to the convict George Barrington and English gentleman Henry Carter, encapsulates something of this concept with the famous lines: “From distant climes, o’er wide-spread seas, we come / Though not with much éclat or beat of drum”. To be without much éclat, to be working poor, was to be Australian.

What does Leong think about the idea of Australian masculinity as essentially working class? “Well, fashion has a lot to say about that. I think Mambo is a great example.” He points me towards a large purple shirt illustrated with colourful biscuits. “This was designed by Reg Mombassa. It takes inspiration from the Hawaiian Aloha shirt but makes it quintessentially Australian. The biscuits are classics: Tim-Tams, Chocolate Wheatens, Iced VoVos and Spicy Fruit Rolls. It imagines the Aussie bloke as a sloppy surfer, a guy who spills food over his shirt in a drunken stupor. The colours are loud and busy, which go against conventional middle-class taste. Mambo sees men as rough outsiders.”

Dr Kean has another perspective.

“Masculinity, it’s always plural, she says; “a shifting set of ideas that are often in contradiction with one another. Fashion is interesting because in the context of Australia, the stereotype is a kind of heroic anti-fashion, one that is white, heterosexual and buoyed by confidence and indifference.”

What does she think about budgie smugglers?

“I think they privilege a masculinity of the body over a masculinity of the mind. They are jocular, aggressive and utilitarian. Wearing them signals a pure engagement with physical activity. The irony is that even though they are associated with heterosexual beach culture, they have also become a symbol of gay pride. Think about Mardi Gras. You’d be hard pressed to find a float without at least one tanned body in Speedos.”

I suggest that Mambo shirts also represent another type of Australian masculinity. Kean agrees, suggesting they evoke a kind of anti-beauty. “They make me think of ‘the Australian ugliness’, a term used by Robin Boyd to refer to Australian architecture, but might also be applied to types of fashion. The man who wears Mambo says ‘I am happy with my lack of rank. I am a messy larrikin and proud of it’.”

One of the ironies of my adult life is that I quite enjoy watching football. There’s something about the glow of bodies on closely clipped grass that leaves me in a trance. I could never go to a game, though; I need to keep the bodies at a distance, because these men are the grown-ups of the boys who beat me. Men wear a lot more pink today than when I was young, even football players themselves, who have embraced hot pink socks, jerseys and boots in support of various charities. But while pink may have become more mainstream, when I hear the “alpha-male” commentary and see the biffo on the field, I can’t help but think that culture still has long way to go before we can shirk the masculine myth.