Impacts of Gut Bacteria on Human Health and Diseases

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Gut Bacteria in Health

2.1. Gut Bacteria and Gut Immune System

2.2. Gut Bacteria Benefit the Host

2.3. Dietary Influence on Gut Bacteria

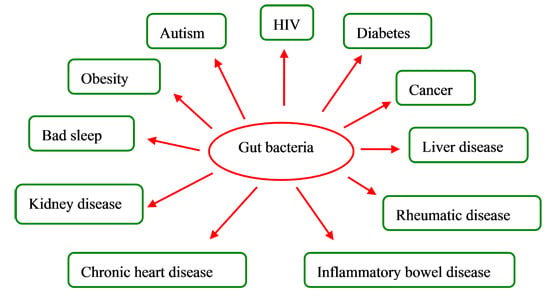

3. Gut Bacteria and Diseases

3.1. Gut Bacteria and Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

3.2. Gut Bacteria and Obesity

3.3. Gut Bacteria and Diabetes

3.4. Gut Bacteria and Liver Diseases

3.5. Gut Bacteria and Chronic Heart Diseases

3.6. Gut Bacteria and Cancers

3.7. Gut Bacteria and HIV

3.8. Gut Bacteria and Autism

3.9. Gut Bacteria and Other Diseases

| Disease | Model | Dysbiosis | Sample | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ulcerative colitis | Mice | ↓Lactobacilli ↑Clostridiales | Colonic | [56] |

| Mice | ↑E. coli | Colonic | [57] | |

| Humans | ↓R. hominis ↓F. prausnitzii | Fecal | [58] | |

| Crohn’s disease | Humans | ↓Bacteroides ↓Bifidobacteria | Fecal | [61] |

| Obesity | Mice | ↓Bacteroides ↑Firmicutes ↑Proteobacteria | Fecal | [67] |

| Type-1diabetes | Humans (children) | ↓Lactobacillus ↓Bifidobacterium ↓Blautia coccoides ↓Eubacterium rectal ↓Prevotella ↑Clostridium ↑Bacteroides ↑Veillonella | Fecal | [87] |

| Type-2 diabetes | Humans | ↓Clostridia ↓Firmicutes ↑Betaproteobacteria | Fecal | [88] |

| Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis | Rats | ↑E. coli | Proximal small intestine | [92] |

| Colorectal cancer | Humans | ↓Prevotella ↓Ruminococcus spp. ↓Pseudobutyrivibrio ruminis ↑Acidaminobacter, ↑Phascolarctobacterium, ↑Citrobacter farmer ↑Akkermansia muciniphila | Fecal | [104] |

| HIV | Humans | ↑Erysipelotrichaceae ↑Proteobacteria ↑Enterobacteriaceae ↓Clostridia ↓Bacteroidia | Proctosigmoid | [112] |

| HIV | Humans | ↓Lactobacilli ↓Bifidobacteria ↑Candida albicans ↑Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Fecal | [113,114] |

| Autistic | Humans (children) | ↑Bacteroides vulgates ↑Desulfovibrio ↓Firmicutes ↓Actinobacteria | Fecal | [122] |

| Rheumatic arthritis | Humans | ↓Bifidobacteria ↓Bacteroides fragilis | Fecal | [127] |

4. Conclusions and Prospects

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clark, J.A.; Coopersmith, C.M. Intestinal crosstalk: A new paradigm for understanding the gut as the “motor” of critical illness. Shock 2007, 28, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, K.; Takeda, K. Regulatory mechanisms of immune responses to intestinal bacteria. Mucosal Immunol. 2009, 2, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, S.C.; Kramer, S. Human mast cells, bacteria, and intestinal immunity. Immunol. Rev. 2007, 217, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, C.; Bik, E.M.; DiGiulio, D.B.; Relman, D.A.; Brown, P.O. Development of the human infant intestinal microbiota. PLoS. Biol. 2007, 5, 1556–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, J.; Smidt, H.; Rijkers, G.T.; de Vos, W.M. Intestinal microbiota in human health and disease: The impact of probiotics. Genes Nutr. 2011, 6, 209–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodmansey, E.J. Intestinal bacteria and ageing. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007, 102, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, D.A.; Artis, D. Intestinal bacteria and the regulation of immune cell homeostasis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2010, 28, 623–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, C.; Macpherson, A.J. Layers of mutualism with commensal bacteria protect us from intestinal inflammation. Gut 2006, 55, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarner, F.; Malagelada, J.R. Gut flora in health and disease. Lancet 2003, 361, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuji, M.; Suzuki, K.; Kinoshita, K.; Fagarasan, S. Dynamic interactions between bacteria and immune cells leading to intestinal IgA synthesis. Semin. Immunol. 2008, 20, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuohy, K.M.; Hinton, D.J.; Davies, S.J.; Crabbe, M.J.; Gibson, G.R.; Ames, J.M. Metabolism of Maillard reaction products by the human gut microbiota—implications for health. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2006, 50, 847–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulluwishewa, D.; Anderson, R.C.; McNabb, W.C.; Moughan, P.J.; Wells, J.M.; Roy, N.C. Regulation of tight junction permeability by intestinal bacteria and dietary components. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfarlane, G.T.; Cummings, J.H. Probiotics and prebiotics: Can regulating the activities of intestinal bacteria benefit health? BMJ 1999, 318, 999–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaza, H. Prostate cancer chemoprevention by soy isoflavones: Role of intestinal bacteria as the “second human genome”. Cancer Sci. 2012, 103, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermann-Bank, M.L.; Skovgaard, K.; Stockmarr, A.; Larsen, N.; Molbak, L. The gut microbiotassay: A high-throughput qPCR approach combinable with next generation sequencing to study gut microbial diversity. BMC Genomics 2013, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, E.E.; Heilig, H.; Ben-Amor, K.; de Vos, W.M. Diversity, vitality and activities of intestinal lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria assessed by molecular approaches. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stecher, B.; Hardt, W. The role of microbiota in infectious disease. Trends Microbiol. 2008, 16, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaud, D.; Tailliez, P.; Anba-Mondoloni, J. Genetic characterization of the β-glucuronidase enzyme from a human intestinal bacterium, Ruminococcus gnavus. Microbiology 2005, 151, 2323–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, Q.M.; Szilagyi, A. Carbohydrate elimination or adaptation diet for symptoms of intestinal discomfort in IBD: Rationales for “Gibsons’ Conundrum”. Int. J. Inflamm. 2012, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanning, D.K.; Rhee, K.J.; Knight, K.L. Intestinal bacteria and development of the β-lymphocyte repertoire. Trends Immunol. 2005, 26, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compare, D.; Coccoli, P.; Rocco, A.; Nardone, O.M.; De Maria, S.; Carteni, M.; Nardone, G. Gut–liver axis: The impact of gut microbiota on non alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2012, 22, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strauch, U.G.; Obermeier, F.; Grunwald, N.; Gurster, S.; Dunger, N.; Schultz, M.; Griese, D.P.; Mahler, M.; Scholmerich, J.; Rath, H.C. Influence of intestinal bacteria on induction of regulatory T cells: Lessons from a transfer model of colitis. Gut 2005, 54, 1546–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpaia, N.; Campbell, C.; Fan, X.Y.; Dikiy, S.; van der Veeken, J.; DeRoos, P.; Liu, H.; Cross, J.R.; Pfeffer, K.; Coffer, P.J.; Rudensky, A.Y. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 2013, 504, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfarlane, S.; Steed, H.; Macfarlane, G.T. Intestinal bacteria and inflammatory bowel disease. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2009, 46, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalanka-Tuovinen, J.; Salonen, A.; Nikkila, J.; Immonen, O.; Kekkonen, R.; Lahti, L.; Palva, A.; de Vos, W.M. Intestinal microbiota in healthy adults: Temporal analysis reveals individual and common core and relation to intestinal symptoms. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landete, J.M. Plant and mammalian lignans: A review of source, intake, metabolism, intestinal bacteria and health. Food Res. Int. 2012, 46, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentealba, C.; Figuerola, F.; Estevez, A.M.; Bastias, J.M.; Munoz, O. Bioaccessibility of lignans from flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum L.) determined by Single Batch in vitro simulation of the digestive Pprocess. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2014, 94, 1729–1738. [Google Scholar]

- Clavel, T.; Henderson, G.; Alpert, C.A.; Philippe, C.; Rigottier-Gois, L.; Dore, J.; Blaut, M. Intestinal bacterial communities that produce active estrogen-like compounds enterodiol and enterolactone in humans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 6077–6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, C.; Frankenfeld, C.L.; Lampe, J.W. Gut bacterial metabolism of the soy isoflavone daidzein: Exploring the relevance to human health. Exp. Biol. Med. 2005, 230, 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.; DeCoffe, D.; Molcan, E.; Gibson, D.L. Diet-induced dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota and the effects on immunity and disease. Nutrients 2012, 4, 1095–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmsen, H.; Wildeboer-Veloo, A.; Raangs, G.C.; Wagendorp, A.A.; Klijn, N.; Bindels, J.G.; Welling, G.W. Analysis of intestinal flora development in breast-fed and formula-fed infants by using molecular identification and detection methods. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2000, 30, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallani, M.; Young, D.; Scott, J.; Norin, E.; Amarri, S.; Adam, R.; Aguilera, M.; Khanna, S.; Gil, A.; Edwards, C.A.; Dore, J. Intestinal microbiota of 6-week-old infants across Europe: Geographic influence beyond delivery mode, breast-feeding, and antibiotics. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2010, 51, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tachon, S.; Lee, B.; Marco, M.L. Diet alters probiotic Lactobacillus persistence and function in the intestine. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 16, 2915–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.D.; Chen, J.; Hoffmann, C.; Bittinger, K.; Chen, Y.Y.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Bewtra, M.; Knights, D.; Walters, W.A.; Knight, R.; et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science 2011, 334, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, L.A.; Maurice, C.F.; Carmody, R.N.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Button, J.E.; Wolfe, B.E.; Ling, A.V.; Devlin, A.S.; Varma, Y.; Fischbach, M.A.; et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014, 505, 559–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.C.; Jenner, A.M.; Low, C.S.; Lee, Y.K. Effect of tea phenolics and their aromatic fecal bacterial metabolites on intestinal microbiota. Res. Microbiol. 2006, 157, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkar, S.G.; Trower, T.M.; Stevenson, D.E. Fecal microbial metabolism of polyphenols and its effects on human gut microbiota. Anaerobe 2013, 23, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koecher, K.J.; Thomas, W.; Slavin, J.L. Healthy subjects experience bowel changes on enteral diets; addition of a fiber blend attenuates stool weight and gut bacteria decreases without changes in gas. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2013, 25, 132–138. [Google Scholar]

- Sofi, M.H.; Gudi, R.; Karumuthil-Melethil, S.; Perez, N.; Johnson, B.M.; Vasu, C. pH of drinking water influences the composition of gut microbiome and type 1 diabetes incidence. Diabetes 2014, 63, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, I.; Boleij, A.; Kortman, G.; Roelofs, R.; Djuric, Z.; Severson, R.K.; Tjalsma, H. Partial associations of dietary iron, smoking and intestinal bacteria with colorectal cancer risk. Nutr. Cancer 2013, 65, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Kong, W.; Jin, C.; Zhao, Y.; Qu, Y.; Xiao, X. Microcalorimetric assay on the antimicrobial property of five hydroxyanthraquinone derivatives in rhubarb (Rheum palmatum L.) to Bifidobacterium adolescentis. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 684–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, G.R.; Roberfroid, M.B. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: Introducing the concept of prebiotics. J. Nutr. 1995, 125, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gibson, G.R.; Probert, H.M.; Loo, J.V.; Rastall, R.A.; Roberfroid, M.B. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: Updating the concept of prebiotics. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2004, 17, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macfarlane, G.T.; Steed, H.; Macfarlane, S. Bacterial metabolism and health-related effects of galacto-oligosaccharides and other prebiotics. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 104, 305–344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ljungh, A.; Wadstrom, T. Lactic acid bacteria as probiotics. Curr. Issues Intest. Microbiol. 2006, 7, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bongaerts, G.; Severijnen, R.; Timmerman, H. Effect of antibiotics, prebiotics and probiotics in treatment for hepatic encephalopathy. Med. Hypotheses 2005, 64, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruis, W. Review article: Antibiotics and probiotics in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 20, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lye, H.S.; Kuan, C.Y.; Ewe, J.A.; Fung, W.Y.; Liong, M.T. The improvement of hypertension by probiotics: Effects on cholesterol, diabetes, renin, and phytoestrogens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 3755–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, A.; Nagpal, R.; Mohania, D.; Behare, P.; Verma, V.; Kumar, P.; Poddar, D.; Aggarwal, P.K.; Henry, C.J.; et al. Cancer-preventing attributes of probiotics: An update. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2010, 61, 473–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneghin, F.; Fabiano, V.; Mameli, C.; Zuccotti, G.V. Probiotics and atopic dermatitis in children. Pharmaceuticals 2012, 5, 727–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilcox, M.H. Clostridium difficile infection and pseudomembranous colitis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2003, 17, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoentjen, F.; Welling, G.W.; Harmsen, H.J.; Zhang, X.; Snart, J.; Tannock, G.W.; Lien, K.; Churchill, T.A.; Lupicki, M.; Dieleman, L.A. Reduction of colitis by prebiotics in HLA-B27 transgenic rats is associated with microflora changes and immunomodulation. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2005, 11, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jostins, L.; Ripke, S.; Weersma, R.K.; Duerr, R.H.; McGovern, D.P.; Hui, K.Y.; Lee, J.C.; Schumm, L.P.; Sharma, Y.; Anderson, C.A.; et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2012, 491, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J.H.; Macfarlane, G.T.; Macfarlane, S. Intestinal bacteria and ulcerative colitis. Curr. Issues Intest. Microbiol. 2003, 4, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bullock, N.R.; Booth, J.C.L.; Gibson, G.R. Comparative composition of bacteria in the human intestinal microflora during remission and active ulcerative colitis. Curr. Issues Intest. Microbiol. 2004, 5, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Heimesaat, M.M.; Fischer, A.; Siegmund, B.; Batra, A.; Loddenkemper, C.; Liesenfeld, O.; Blaut, M.; Gobel, U.B.; Schumann, R.R.; Bereswill, S. Shifts towards pro-inflammatory intestinal bacteria aggravate acute murine colitis and ileitis via toll-like-receptor signaling. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 29743, 81–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kamada, N.; Hisamatsu, T.; Okamoto, S.; Sato, T.; Matsuoka, K.; Arai, K.; Nakai, T.; Hasegawa, A.; Inoue, N.; Watanabe, N.; Akagawa, K.S.; Hibi, T. Abnormally differentiated subsets of intestinal macrophage play a key role in Th1-dominant chronic colitis through excess production of IL-12 and IL-23 in response to bacteria. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 6900–6908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machiels, K.; Joossens, M.; Sabino, J.; de Preter, V.; Arijs, I.; Eeckhaut, V.; Ballet, V.; Claes, K.; van Immerseel, F.; Verbeke, K.; et al. A decrease of the butyrate-producing species Roseburia hominis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut 2014, 63, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepage, P.; Haesler, R.; Spehlmann, M.E.; Rehman, A.; Zvirbliene, A.; Begun, A.; Ott, S.; Kupcinskas, L.; Dore, J.; Raedler, A.; Schreiber, S. Twin study indicates loss of interaction between microbiota and mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, A. Oral micro-particulate colon targeted drug delivery system for the treatment of Crohn’s disease: A review. Int. J. Life Sci. Pharm. Res. 2012, 1, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Seksik, P.; Rigottier-Gois, L.; Gramet, G.; Sutren, M.; Pochart, P.; Marteau, P.; Jian, R.; Dore, J. Alterations of the dominant faecal bacterial groups in patients with Crohn’s disease of the colon. Gut 2003, 52, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joossens, M.; Huys, G.; Cnockaert, M.; de Preter, V.; Verbeke, K.; Rutgeerts, P.; Vandamme, P.; Vermeire, S. Dysbiosis of the faecal microbiota in patients with Crohn’s disease and their unaffected relatives. Gut 2011, 60, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gevers, D.; Kugathasan, S.; Denson, L.A.; Vazquez-Baeza, Y.; van Treuren, W.; Ren, B.; Schwager, E.; Knights, D.; Song, S.J.; Yassour, M.; et al. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset Crohn’s disease. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, S.T.; Mitchell, H.M.; Eng, W.R.; Zhang, L.; Day, A.S. Sustained modulation of intestinal bacteria by exclusive enteral nutrition used to treat children with Crohn’s disease. Aliment. Pharm. Ther. 2008, 28, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tighe, M.P.; Cummings, J.; Afzal, N.A. Nutrition and inflammatory bowel disease: Primary or adjuvant therapy. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2011, 14, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, S.L.; Chi, M.M.; Scull, B.P.; Rigby, R.; Schwerbrock, N.; Magness, S.; Jobin, C.; Lund, P.K. High-fat diet: Bacteria interactions promote intestinal inflammation which precedes and correlates with obesity and insulin resistance in mouse. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hildebrandt, M.A.; Hoffmann, C.; Sherrill-Mix, S.A.; Keilbaugh, S.A.; Hamady, M.; Chen, Y.; Knight, R.; Ahima, R.S.; Bushman, F.; Wu, G.D. High-fat diet determines the composition of the murine gut microbiome independently of obesity. Gastroenterology 2009, 137, 1716–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armougom, F.; Henry, M.; Vialettes, B.; Raccah, D.; Raoult, D. Monitoring bacterial community of human gut microbiota reveals an increase in Lactobacillus in obese patients and Methanogens in anorexic patients. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluny, N.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Sharkey, K.A. Cannabinoid signalling regulates inflammation and energy balance: The importance of the brain-gut axis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2012, 26, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, J.; Burke, B.; Ford, D.; Garvin, G.; Korn, C.; Sulis, C.; Bhadelia, N. Possible association between obesity and Clostridium difficile infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 1791–1798. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.V.; Frassetto, A.; Kowalik, E.J., Jr.; Nawrocki, A.R.; Lu, M.M.; Kosinski, J.R.; Hubert, J.A.; Szeto, D.; Yao, X.; Forrest, G.; Marsh, D.J. Butyrate and propionate protect against diet-Induced obesity and regulate gut hormones via free fatty acid receptor 3-independent mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e352404. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, C.P.; Shanahan, F. Gut microbiota and obesity: Role in aetiology and potential therapeutic target. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2014, 28, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorissen, L.; Raes, K.; Weckx, S.; Dannenberger, D.; Leroy, F.; de Vuyst, L.; de Smet, S. Production of conjugated linoleic acid and conjugated linolenic acid isomers by Bifidobacterium species. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 2257–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.Y.; Park, J.H.; Seok, S.H.; Baek, M.W.; Kim, D.J.; Lee, K.E.; Paek, K.S.; Lee, Y.; Park, J H. Human originated bacteria, Lactobacillus rhamnosus PL60, produce conjugated linoleic acid and show anti-obesity effects in diet-induced obese mice. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1761, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Poutahidis, T.; Kleinewietfeld, M.; Smillie, C.; Levkovich, T.; Perrotta, A.; Bhela, S.; Varian, B.J.; Ibrahim, Y.M.; Lakritz, J.R.; Kearney, S.M.; et al. Microbial reprogramming inhibits western diet-associated obesity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e685967. [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian, D.; Hao, T.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2392–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De los Reyes-Gavilan, C.G.; Delzenne, N.M.; Gonzalez, S.; Gueimonde, M.; Salazar, N. Development of functional foods to fight against obesity Opportunities for probiotics and prebiotics. Agro Food Ind. Hi Tech 2014, 25, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kelishadi, R.; Farajian, S.; Safavi, M.; Mirlohi, M.; Hashemipour, M. A randomized triple-masked controlled trial on the effects of synbiotics on inflammation markers in overweight children. J. Pediatr. 2014, 90, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridaura, V.K.; Faith, J.J.; Rey, F.E.; Cheng, J.; Duncan, A.E.; Kau, A.L.; Griffin, N.W.; Lombard, V.; Henrissat, B.; Bain, J.R.; et al. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science 2013, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.W.; Parkhill, J. Fighting obesity with bacteria. Science 2013, 341, 1069–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, S.S.; Chen, Z.Y.; Guo, L.L.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Stien, X.; Coulon, D. Incorporation of therapeutically modified bacteria into gut microbiota prevents obesity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burcelin, R.; Serino, M.; Chabo, C.; Blasco-Baque, V.; Amar, J. Gut microbiota and diabetes: From pathogenesis to therapeutic perspective. Acta Diabetol. 2011, 48, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cani, P.D.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Fava, F.; Knauf, C.; Burcelin, R.G.; Tuohy, K.M. Selective increases of bifidobacteria in gut microflora improve high-fat diet induced diabetes in mice through a mechanism associated with endotoxaemia. Diabetologia 2007, 50, 2374–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musso, G.; Gambino, R.; Cassader, M. Interactions between gut microbiota and host metabolism predisposing to obesity and diabetes. Annu. Rev. Med. 2011, 62, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nara, N.; Alkanani, A.K.; Ir, D.; Robertson, C.E.; Wagner, B.D.; Frank, D.N.; Zipris, D. The role of the intestinal microbiota in type 1 diabetes. Clin. Immunol. 2013, 146, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.T.; Davis-Richardson, A.G.; Giongo, A.; Gano, K.A.; Crabb, D.B.; Mukherjee, N.; Casella, G.; Drew, J.C.; Ilonen, J.; Knip, M.; et al. Gut microbiome metagenomics analysis suggests a functional model for the development of autoimmunity for type 1 diabetes. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murri, M.; Leiva, I.; Gomez-Zumaquero, J.M.; Tinahones, F.J.; Cardona, F.; Soriguer, F.; Queipo-Ortuno, M.I. Gut microbiota in children with type 1 diabetes differs from that in healthy children: A case-control study. BMC Med. 2013, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, N.; Vogensen, F.K.; van den Berg, F.; Nielsen, D.S.; Andreasen, A.S.; Pedersen, B.K.; Abu Al-Soud, W.; Sorensen, S.J.; Hansen, L.H.; Jakobsen, M. Gut microbiota in human adults with type 2 diabetes differs from non-diabetic adults. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e90852. [Google Scholar]

- Amar, J.; Chabo, C.; Waget, A.; Klopp, P.; Vachoux, C.; Bermudez-Humaran, L.G.; Smirnova, N.; Berge, M.; Sulpice, T.; Lahtinen, S.; et al. Intestinal mucosal adherence and translocation of commensal bacteria at the early onset of type 2 diabetes: Molecular mechanisms and probiotic treatment. EMBO Mol. Med. 2011, 3, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugman, S.; Klatter, F.A.; Visser, J.; Wildeboer-Veloo, A.; Harmsen, H.; Rozing, J.; Bos, N.A. Antibiotic treatment partially protects against type 1 diabetes in the Bio-Breeding diabetes-prone rat. Is the gut flora involved in the development of type 1 diabetes? Diabetologia 2006, 49, 2105–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morowitz, M.J.; Carlisle, E.M.; Alverdy, J.C. Contributions of intestinal bacteria to nutrition and metabolism in the critically ill. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 91, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.C.; Zhao, W.; Li, S. Small intestinal bacteria overgrowth decreases small intestinal motility in the NASH rats. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajiya, M.; Sato, K.; Silva, M.; Ouhara, K.; Do, P.M.; Shanmugam, K.T.; Kawai, T. Hydrogen from intestinal bacteria is protective for Concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 386, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutlu, E.; Keshavarzian, A.; Engen, P.; Forsyth, C.B.; Sikaroodi, M.; Gillevet, P. Intestinal dysbiosis: A possible mechanism of alcohol-induced endotoxemia and alcoholic steatohepatitis in rats. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2009, 33, 1836–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llovet, J.M.; Bartoli, R.; March, F.; Planas, R.; Vinado, B.; Cabre, E.; Arnal, J.C.; Pere, A.; Vicenc, G.; Miquel, A. Translocated intestinal bacteria cause spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic rats: Molecular epidemiologic evidence. J. Hepatol. 1998, 28, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gottardi, A.; McCoy, K.D. Evaluation of the gut barrier to intestinal bacteria in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2011, 55, 1181–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandek, A.; Bauditz, J.; Swidsinski, A.; Buhner, S.; Weber-Eibel, J.; von Haehling, S.; Schroedl, W.; Karhausen, T.; Doehner, W.; Rauchhaus, M.; et al. Altered intestinal function in patients with chronic heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 50, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandek, A.; Anker, S.D.; von Haehling, S. The gut and intestinal bacteria in chronic heart failure. Curr. Drug. Metab. 2009, 10, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krack, A.; Sharma, R.; Figulla, H.R.; Anker, S.D. The importance of the gastrointestinal system in the pathogenesis of heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2005, 26, 2368–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, M.; Fuentes, M.C.; Audivert, S.; Bonachera, M.A.; Peiro, S.; Cune, J. Lactobacillus plantarum CECT 7527, 7528 and 7529: Probiotic candidates to reduce cholesterol levels. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, V.; Su, J.D.; Koprowski, S.; Hsu, A.N.; Tweddell, J.S.; Rafiee, P.; Gross, G.J.; Salzman, N.H.; Baker, J.E. Intestinal microbiota determine severity of myocardial infarction in rats. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 1727–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.J.; Ko, G.S.; Oh, D.G.; Kim, J.S.; Noh, K.; Kang, W.; Yoon, W.K.; Kim, H.C.; Jeong, H.G.; Jeong, T.C. Role of metabolism by intestinal microbiota in pharmacokinetics of oral baicalin. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2014, 37, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, F.F.; Esworthy, S.; Chu, P.G.; Huycke, M.; Doroshow, J. Bacteria-induced intestinal cancer in mice with disrupted Gpx1 and Gpx2 genes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 351, 165–166. [Google Scholar]

- Weir, T.L.; Manter, D.K.; Sheflin, A.M.; Barnett, B.A.; Heuberger, A.L.; Ryan, E.P. Stool microbiome and metabolome differences between colorectal cancer patients and healthy adults. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e70803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boleij, A.; Tjalsma, H. Gut bacteria in health and disease: A survey on the interface between intestinal microbiology and colorectal cancer. Biol. Rev. 2012, 87, 701–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.; Rivenson, A.; Tomita, M.; Shimamura, S.; Ishibashi, N.; Reddy, B.S. Bifidobacterium longum, a lactic acid-producing intestinal bacterium inhibits colon cancer and modulates the intermediate biomarkers of colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 1997, 18, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viaud, S.; Saccheri, F.; Mignot, G.; Yamazaki, T.; Daillere, R.; Hannani, D.; Enot, D.P.; Pfirschke, C.; Engblom, C.; Pittet, M.J.; et al. The intestinal microbiota modulates the anticancer immune effects of cyclophosphamide. Science 2013, 342, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poutahidis, T.; Cappelle, K.; Levkovich, T.; Lee, C.W.; Doulberis, M.; Ge, Z.M.; Fox, J.G.; Horwitz, B.H.; Erdman, S.E. Pathogenic intestinal bacteria enhance prostate cancer development via systemic activation of immune cells in mice. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e739338. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama, Y.; Masumori, N.; Fukuta, F.; Yoneta, A.; Hida, T.; Yamashita, T.; Minatoya, M.; Nagata, Y.; Mori, M.; Tsuji, H.; et al. Influence of isoflavone intake and equol-producing intestinal flora on prostate cancer risk. Asian Pacific. J. Cancer Prev. 2013, 14, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A.; Rizzardini, G.; Van’T Land, B.; Amor, K.B.; van Schaik, J.; Torti, C.; Bandera, A.; Knol, J.; Benlhassan-Chahour, K.; Trabattoni, D.; et al. Specific prebiotics modulate gut microbiota and immune activation in HAART-naive HIV-infected adults: Results of the “COPA” pilot randomized trial. Mucosal Immunol. 2011, 4, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajac, V.; Stevurkova, V.; Matelova, L.; Ujhazy, E. Detection of HIV-1 sequences in intestinal bacteria of HIV/AIDS patients. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 2007, 28, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vujkovic-Cvijin, I.; Dunham, R.M.; Iwai, S.; Maher, M.C.; Albright, R.G.; Broadhurst, M.J.; Hernandez, R.D.; Lederman, M.M.; Huang, Y.; Somsouk, M.; et al. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota is associated with HIV disease progression and tryptophan aatabolism. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A.; Tincati, C.; Rizzardini, G.; Torti, C.; Quirino, T.; Haarman, M.; Ben Amor, K.; van Schaik, J.; Vriesema, A.; Knol, J.; et al. Early impairment of gut function and gut flora supporting a role for alteration of gastrointestinal mucosa in human immunodeficiency virus pathogenesis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 757–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, B.W.; Wheeler, K.B.; Ataya, D.G.; Garleb, K.A. Safety and tolerance of Lactobacillus reuteri supplementation to a population infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1998, 36, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemsworth, J.; Hekmat, S.; Reid, G. The development of micronutrient supplemented probiotic yogurt for people living with HIV: Laboratory testing and sensory evaluation. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2011, 12, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.B.; Johansen, L.J.; Powell, L.D.; Quig, D.; Rubin, R.A. Gastrointestinal flora and gastrointestinal status in children with autism-comparisons to typical children and correlation with autism severity. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G. Mind-altering microorganisms: The impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2012, 13, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heberling, C.A.; Dhurjati, P.S.; Sasser, M. Hypothesis for a systems connectivity model of autism spectrum disorder pathogenesis: Links to gut bacteria, oxidative stress, and intestinal permeability. Med. Hypotheses 2013, 80, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.L.; Liu, C.X.; Finegold, S.A. Real-time PCR quantitation of clostridia in feces of autistic children. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2004, 70, 6459–6465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finegold, S.M. State of the art; microbiology in health and disease. Intestinal bacterial flora in autism. Anaerobe 2011, 17, 367–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finegold, S.M.; Molitoris, D.; Song, Y.L.; Liu, C.X.; Vaisanen, M.L.; Bolte, E.; McTeague, M.; Sandler, R.; Wexler, H.; Marlowe, E.M.; et al. Gastrointestinal microflora studies in late-onset autism. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 351, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finegold, S.M. Desulfovibrio species are potentially important in regressive autism. Med. Hypotheses 2011, 77, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Angelis, M.; Piccolo, M.; Vannini, L.; Siragusa, S.; de Giacomo, A.; Serrazzanetti, D.I.; Cristofori, F.; Guerzoni, M.E.; Gobbetti, M.; Francavilla, R. Fecal microbiota and metabolome of children with autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, S.; Komada, Y.; Kamiya, T.; Shirakawa, S. A pilot study of the relationship between bowel habits and sleep health by actigraphy measurement and fecal flora analysis. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2008, 27, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taurog, J.D.; Richardson, J.A.; Croft, J.T.; Simmons, W.A.; Zhou, M.; Fernandez-Sueiro, J.L.; Balish, E.; Hammer, R.E. The germfree state prevents development of gut and joint inflammatory disease in HLA-B27 transgenic rats. J. Exp. Med. 1994, 180, 2359–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehakova, Z.; Capkova, J.; Stepankova, R.; Sinkora, J.; Louzecka, A.; Ivanyi, P.; Weinreich, S. Germ-free mice do not develop ankylosing enthesopathy, a spontaneous joint disease. Hum. Immunol. 2000, 61, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeoh, N.; Burton, J.P.; Suppiah, P.; Reid, G.; Stebbings, S. The role of the microbiome in rheumatic diseases. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2013, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotanko, P.; Carter, M.; Levin, N.W. Intestinal bacterial microflora—a potential source of chronic inflammation in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 2006, 21, 2057–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.A.; Macfarlane, G.T. Enumeration of human colonic bacteria producing phenolic and indolic compounds: Effects of pH, carbohydrate availability and retention time on dissimilatory aromatic amino acid metabolism. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1996, 81, 288–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiba, T.; Kawakami, K.; Sasaki, T.; Makino, I.; Kato, I.; Kobayashi, T.; Uchida, K.; Kaneko, K. Effects of intestinal bacteria-derived p-cresyl sulfate on Th1-type immune response in vivo and in vitro. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2014, 274, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.-J.; Li, S.; Gan, R.-Y.; Zhou, T.; Xu, D.-P.; Li, H.-B. Impacts of Gut Bacteria on Human Health and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 7493-7519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16047493

Zhang Y-J, Li S, Gan R-Y, Zhou T, Xu D-P, Li H-B. Impacts of Gut Bacteria on Human Health and Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2015; 16(4):7493-7519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16047493

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yu-Jie, Sha Li, Ren-You Gan, Tong Zhou, Dong-Ping Xu, and Hua-Bin Li. 2015. "Impacts of Gut Bacteria on Human Health and Diseases" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 16, no. 4: 7493-7519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms16047493