Federal Court of Australia

The Agency Group Australia Limited v H.A.S. Real Estate Pty Ltd [2023] FCA 482

ORDERS

DATE OF ORDER: |

THE COURT ORDERS THAT:

1. The originating application be dismissed.

2. The parties file and serve written submissions on the question of costs (not exceeding 5 pages), together with any affidavit or affidavits in support by 24 May 2023.

3. The parties file and serve any written submissions in reply (not exceeding 3 pages), together with any affidavit or affidavits in support by 31 May 2023.

Note: Entry of orders is dealt with in Rule 39.32 of the Federal Court Rules 2011.

JACKMAN J

Introduction

1 These proceedings concern allegations that the respondents have:

(a) infringed registered trade marks pursuant to s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) (the Trade Marks Act);

(b) engaged in conduct that is misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the Australian Consumer Law, being Sch 2 to the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (ACL);

(c) made false or misleading representations in contravention of s 29(1)(g), (h) and (k) of the ACL to the effect that:

(i) the first respondent’s (H.A.S. Real Estate) real estate agency services have the sponsorship or approval of the applicants; and/or

(ii) H.A.S. Real Estate has the sponsorship or approval, or an affiliation with, the applicants; and

(d) passed off the real estate agency services of H.A.S. Real Estate as being connected or associated with the applicants or their services.

2 The applicants seek a range of declaratory, injunctive and pecuniary relief. The claim for interlocutory relief was not pursued in light of the Court’s ability to offer an early final hearing. There has not been any separation of issues of liability and injunctive relief, on the one hand, and pecuniary remedies, on the other hand. Accordingly, this is a trial on all issues in the proceedings. However, at the end of his final address, Mr Heerey KC, who appeared for the applicants, abandoned the claims for pecuniary remedies (T146.29-30).

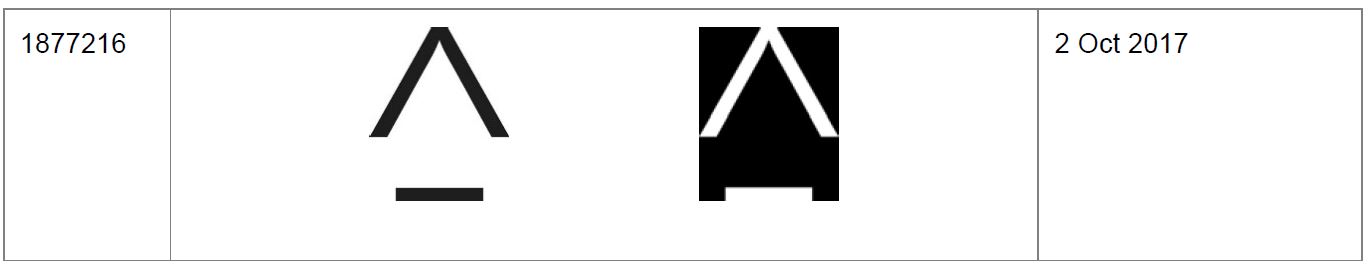

3 The second applicant (Ausnet) is a wholly owned subsidiary of the first applicant (The Agency Group), and is the registered owner of the following Australian trade marks, which have been registered with effect from the priority dates given below in relation to a range of real estate services in class 36 (the Registered Marks):

I refer to the first of those marks, No. 1836914, as the AGENCY Mark and the second, No. 1877216, as the Logo Mark.

4 The third applicant (The Agency Sales NSW) is also a wholly owned subsidiary of The Agency Group, and conducts some aspects of the business of The Agency Group within New South Wales. The Agency Group and The Agency Sales NSW are authorised by Ausnet to use the Registered Marks.

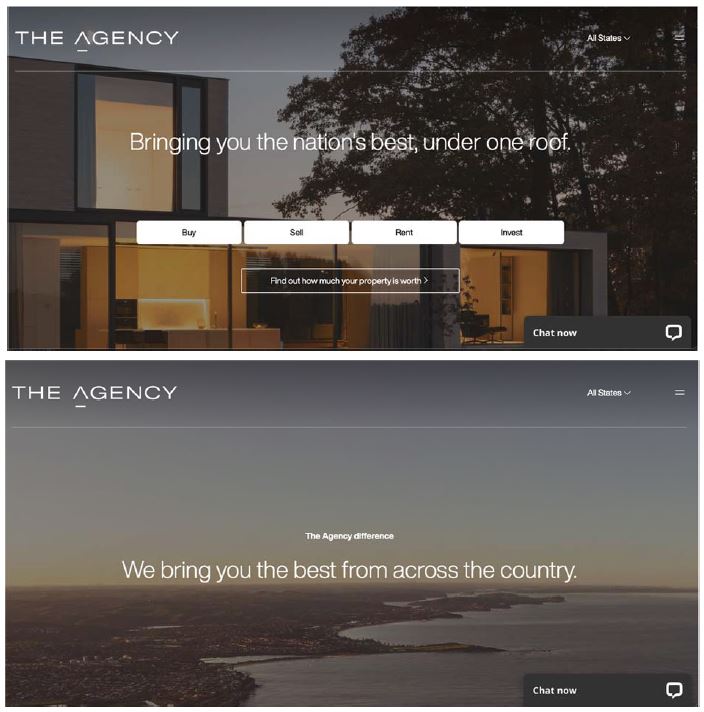

5 Since about 2017, The Agency Group has promoted its business by a way of a get-up featuring the Registered Marks, against a dark background, such as a dark sky at dusk. Examples are given in the two screenshots below from The Agency Group’s current website (dating from some unidentified time after January 2023):

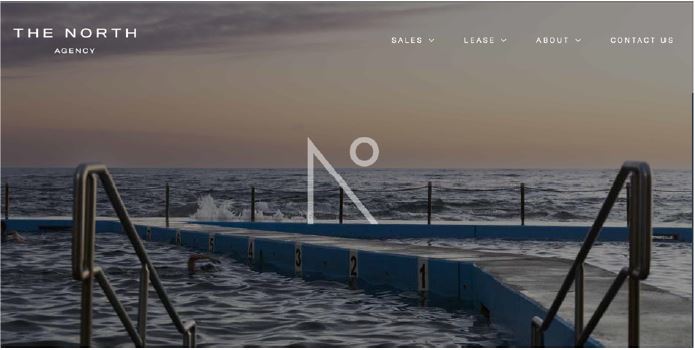

6 Since March this year, H.A.S. Real Estate has promoted its real estate agency business using get-up featuring the name THE NORTH AGENCY in white block capitals and the logo that is  against a dark background, including a dark sky at dusk. An example is given in the following screenshot from the website of H.A.S. Real Estate:

against a dark background, including a dark sky at dusk. An example is given in the following screenshot from the website of H.A.S. Real Estate:

I refer to the logo as the N Logo.

7 The real estate business of H.A.S. Real Estate is located in Dee Why, in the Northern Beaches region of Sydney. One of the many offices of The Agency Group is located in Manly, a suburb in the Northern Beaches. Another office is located in Neutral Bay, a suburb close to the Northern Beaches. There is also an office at Lindfield, which is inland from the Northern Beaches in the area of Sydney known as the North Shore.

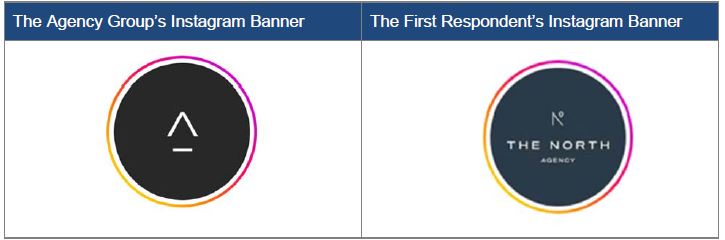

8 Both The Agency Group and H.A.S. Real Estate promote their business by way of Instagram accounts, and the respective banners of those accounts are shown below (extracted from paragraph 8 of the applicants’ concise statement):

It should be observed that the circular shape of those banners and the coloured circle around the banners are features imposed by Instagram itself in certain circumstances on those with Instagram accounts. I also note that by showing these images side-by-side (and also the ones in the two paragraphs below), the applicants were not suggesting that the relevant comparison for the purpose of any of their causes of action should be conducted side-by-side which, as I indicate below, would be contrary to principle and authority. It is merely a convenient way of presenting the evidence.

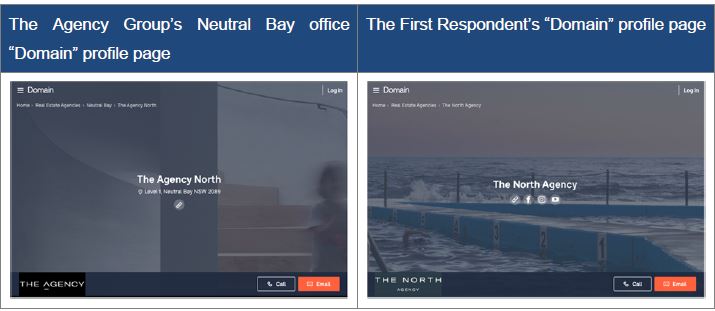

9 Both businesses are also promoted on the “Domain” website by way of agency profile pages which appear as shown below (extracted from paragraph 9 of the applicants’ concise statement):

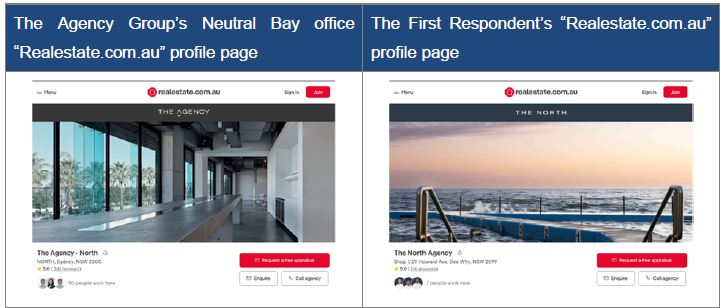

10 Similarly, both businesses are promoted on the “realestate.com.au” website by way of profile pages as follows (extracted from paragraph 10 of the applicants’ concise statement):

11 It should be observed that the standardised layout of the agency profile pages on the Domain and the realestate.com.au websites is imposed by the operators of those websites, and therefore applies to all real estate agencies with agency profile pages.

12 The applicants also sought orders (of the same kind sought against H.A.S. Real Estate) against the directors of H.A.S. Real Estate, being the second and third respondents, Mr Aldren and Mr Sila. However, those claims were abandoned at the very end of Mr Heerey’s final address when I asked him if the claims against Mr Aldren and Mr Sila were still pressed. After an adjournment of about 5 minutes, Mr Heerey KC said that they were not: T146.9-15.

13 I will come in due course to consider the particular wrongs which are alleged by the applicants against the respondents. However, I will first deal with the evidence concerning the respective sets of litigants.

The Agency Group

14 The Agency Group operates a real estate business providing services in residential sales, project marketing, property management and finance to customers across Australia. The brand “The Agency” was first used in Australia by The Agency Pty Ltd, and Ausnet acquired the business from that entity in 2016. The business operated by Ausnet (and other businesses within the “Ausnet Financial Services” group of companies) was subsequently listed on the Australian Stock Exchange on about 14 December 2016, following the acquisition of The Agency Group. In December 2017, the name of the listed company was changed to The Agency Group Australia Ltd, to reflect the fact that “The Agency” brand had grown to become the central brand of the business.

15 The Agency Group currently has over 400 agents Australia-wide, including 26 offices in New South Wales operating from 21 physical locations, with the Northern Beaches region specifically serviced by its offices in Manly and Neutral Bay. In the financial year ending 30 June 2022, The Agency Group and its controlled entities:

(a) sold a total of 5,709 properties with an aggregate value of $5.9 billion;

(b) received $72.7 million in revenue and $102.5 million in gross commission income

(c) had 3,469 rental properties under management as at 30 June 2022;

(d) spent $2.28 million on advertising and promotion expenses; and

(e) valued their goodwill at $10.7 million.

In the six months to 31 December 2022, The Agency Group and its controlled entities:

(a) listed 3,124 new properties for sale;

(b) sold 2,847 properties at an aggregate value of $2.556 billion;

(c) earned $45.7 million in gross commission income, and $37.5 million in combined group revenue; and

(d) had 4,908 rental properties under management.

16 The Agency Group operates from 26 offices in New South Wales, including:

(a) The Agency North West (which has been registered as a business name since 11 June 2021);

(b) The Agency Northern NSW (which has been registered as a business name since 11 June 2021); and

(c) The Agency Upper North Shore (which has been registered as a business name since 18 September 2020).

17 In the period from February 2017 until 29 March 2023, the real estate sales made by The Agency Group in New South Wales totalled $2,788.5 million. In relation to the Northern Beaches region, the real estate sales made by The Agency Group since the financial year ended 30 June 2018 through to the end of March 2023 totalled $239.0 million. In the 12 months to 30 March 2023, The Agency Group’s office in Manly sold 23 properties, with another five for sale as at 30 March 2023, and leased seven properties with another one for rent. In the 12 months to 30 March 2023, The Agency Group’s Neutral Bay office sold 191 properties with another 35 still for sale, and leased 308 properties with another 16 still for rent.

18 Mr Jensen, the executive chairman and chief operating officer of The Agency Group says in his principal affidavit of 31 March 2023 that since February 2017, The Agency Group has listed 23,574 properties in Australia for sale, 21,069 of which resulted in sales. Of those listings, Mr Jensen says that 7,401 properties were in New South Wales and 6,568 resulted in sales. More specifically, 1,530 of those listings are said by Mr Jensen to be of properties in the northern region (a much wider region than the Northern Beaches region), 1,225 of which resulted in sales.

19 The Agency Group conducts online marketing of its business through its own website, through an Instagram account, and by way of the third-party real estate websites known as Domain and realestate.com.au.

20 The website of The Agency Group itself is of considerable importance to the business of The Agency Group. In the period from 1 February 2017 to 28 February 2023:

(a) there were a total of 3,684,307 users of that website from within Australia;

(b) 1,876,816 of those users were in New South Wales;

(c) there were 6,047,089 total sessions; and

(d) there were 12,459,520 total page views.

21 In around October 2016, The Agency Group created an account on Instagram. Since then, The Agency Group has made more than 2,000 posts on Instagram, most of which have prominently displayed one or both of the Registered Marks, and many of them display those marks against a dark background.

22 Since January 2017, The Agency Group has operated profiles on the realestate.com.au website under various titles referring to particular geographic areas. Similarly, since January 2017, The Agency Group has operated profiles on the Domain website under various titles referring to particular geographic areas. In the financial year ending 30 June 2022 and subsequently, the Manly and Neutral Bay offices of The Agency Group, which serviced the Northern Beaches area, have spent the following amounts on advertising properties for sale:

(a) $1,871,559 on realestate.com.au; and

(b) $2,472,684.54 on Domain.

23 Performance summaries which have been generated by Domain indicate that the total page views for both sale and rental listings by The Agency Group were:

(a) 13,107,000 in New South Wales, for the 12 months to the end of March 2023; and

(b) 2,046,076 for the Neutral Bay and Manly offices for the 12 months to the end of March 2023.

24 Performance data which have been generated by realestate.com.au indicate that The Agency Group had a total aggregate of property views of:

(a) 8,748,102 in New South Wales, for the 12 months to the end of March 2023;

(b) 15,246,484 for all other States and Territories combined in the same period; and

(c) 1,868,000 for its Neutral Bay and Manly offices for the same period.

25 The Agency Group’s revenue for the period from February 2017 until 29 March 2023 attributable to its advertising on both realestate.com.au and Domain platforms was a total of $39,836,115.

26 As to other promotional material, The Agency Group distributes printed promotional material about the subject properties and such publications have prominently featured the Registered Marks. Approximately 80% of the sales campaigns by The Agency Group have involved the distribution of between 50 and 5,000 “just listed” promotional cards or brochures in the areas where those properties are situated. Many of The Agency Group’s agents also distribute their own printed promotional material, all of which prominently display the Registered Marks and (less prominently) the website URL, in their respective areas in quantities as high as 10,000 per month. In addition, The Agency Group promotes the sale or lease of their clients’ properties by erecting signboards at those properties which prominently feature their branding. Approximately 90% of The Agency Group’s sales campaigns have involved the display of signboards at each such property. The signboards use the Registered Marks.

27 Mr Jensen says in his affidavit that word of mouth is very important as a means of attracting clients in the market for real estate agency services, and for that reason it is a standard practice for real estate agents to ask their clients to recommend them to new prospective clients after closing a sale. Mr Jensen says that online marketing is a centrally important means of advertising and promoting real estate agency services.

28 In addition, Mr Jensen refers to The Agency Group sponsoring high profile sporting teams and events in which The Agency Group’s name and branding feature prominently. For example, The Agency Group is a sponsor and “Real Estate Partner” of the Australian Turf Club, which owns and operates thoroughbred racing, events and hospitality venues across Sydney. The Agency Group is also a sponsor and the “Real Estate Partner” of the Hawthorn Football Club and a sponsor of the Brisbane City Football Club.

29 In terms of the relative importance of the agency, as distinct from individual agents, in attracting business, Mr Jensen explains that the business model of The Agency Group has always been to put agents first. Mr Jensen says that consumers of real estate agency services place importance on the trustworthiness and awareness of real estate agents. He says that the brand of a real estate agency under which an individual agent supplies their services is a way by which consumers can identify those qualities by verifying and assessing the past performance of the agency with which that agent is associated. He says that such a consumer’s experience with an individual real estate agent will affect the reputation of the agency and the brand under which that agent supplied their services, in that if the experience is positive then this will contribute to the value of that reputation, and if it is negative, then it will detract from that value. Mr Jensen agreed that the customer’s contact with the agent is important because it is the individual agent whom the customer wants to know and, hopefully, respect: T57.31-34.

30 In an article sponsored by The Agency Group in “The Real Estate Conversation” on 26 May 2021, Mr Lahood (the CEO of Real Estate at The Agency Group) wrote that 80% of his business as a sales agent came from his “past” client database. He placed the word “past” in quotation marks, as the comment follows a statement by Mr Lahood that: “Your past clients aren’t in the past. They’re current clients.” The material used in 2017 for The Agency Group’s website includes the statement: “brands don’t sell houses, people do”.

The Respondents and The North Agency

31 Since March 2023, H.A.S. Real Estate has operated a real estate business known as “The North Agency” in the Northern Beaches region of Sydney. The directors of H.A.S. Real Estate, Mr Aldren and Mr Sila, both grew up in the Northern Beaches region of Sydney and have lived in that area since that time.

32 Mr Aldren has worked in the real estate industry in that region since 2006. From 2012 until 2018 he worked for Raine & Horne Dee Why Collaroy and from about 2015 he was consistently ranked in the top 10 agents for Raine & Horne in New South Wales based on sales and commission. In 2018, he was ranked number 4 in Australia and wrote over $1 million in commission. From 2019 until January 2023, Mr Aldren worked at Upstate (previously Raine & Horne Dee Why Collaroy), an independent real estate business in Dee Why. He was the number 1 ranked agent at Upstate based on the number of sales transactions. As a real estate agent, he has always worked on the Northern Beaches. On average in the last 10 years, he has listed and sold around 50 to 70 properties a year.

33 Mr Sila has worked in real estate since 2007. His experience includes having worked in property management and then sales at the Novak Agency based in Dee Why, working as a sales executive at Stone, another real estate agency in Dee Why for about 4 years, and for about five years having been contracted with Upstate in Dee Why, which specialises in the Northern Beaches property market. In the years 2020-2022 inclusive, Mr Sila was among the top 3 performers out of 16 agents for Upstate based on the value of properties sold. In addition to his sales experience, Mr Sila has about 5 years’ experience in property management (that is, managing rental properties on behalf of landlords), and has been managing the rent roll at The North Agency.

34 Mr Aldren explains that the name, The North Agency, arose during a conversation in about 2021 with a colleague in a café in which Mr Aldren expressed a desire to set up his own business and said that he didn’t want his name on the door, but that he wanted “something cool but based on where we are on the northern beaches”. His colleague suggested “The North Agency” and Mr Aldren said in his affidavit that he liked the ring of that name. Mr Aldren says that in his experience, it is important for the name to include, at least initially, a word to describe what the business did. He thought that “The North Real Estate Agency” was too much of a mouthful. Mr Aldren says, and I accept, that at no time during his conversation with his colleague did they discuss “The Agency”, being a reference to the business conducted by the applicants. Mr Aldren says that that business was not in his mind during the conversation and he did not regard The Agency as a competitor on the Northern Beaches. At that stage he did not think that they even had an office on the Northern Beaches. He regarded the main competitors of Upstate on the Northern Beaches as being Cunningham, Belle and to a lesser extent Doyle Spillane and for high end properties, Clarke & Hummel.

35 Serious discussions and plans between Mr Aldren and Mr Sila about setting up an independent real estate agency began in about mid-November 2022. Mr Aldren became aware of The Agency Group’s office located in Manly in around mid-2022, but still did not regard The Agency Group as a competitor on the Northern Beaches. Mr Aldren suggested to Mr Sila the name “The North Agency”, which Mr Sila liked. Mr Sila said that he wanted a name that reflected their connections to the local community and area, as they had both grown up and worked in the Northern Beaches, ie “The North”. Mr Sila added that in his experience, “north” is a word that comes up in real estate sales all the time, as nearly all buyers want a property that faces north to get the natural light and sunshine. Mr Sila added that “The North” also suggests the idea of “find your true north” which he sees as a positive value. Mr Sila said that the “Agency” component of “The North Agency” was not something that he considered very carefully at all, and for him it simply described the real estate business, and he thought it sounded good with “The North” and it flowed.

36 Mr Aldren and Mr Sila had discussions in December 2022 concerning the name with Mr Dan Argent of UrbanX, and Mr Argent sent a mock-up of some logos for “The North Agency” and “The NTH”. UrbanX provides back-of-house, branding, marketing, and administrative services to independent real estate agency businesses. Mr Argent also sent a text message with a logo he had found which had a degree symbol after the letters “NTH”, which Mr Aldren liked as it reinforced the location and direction. A further discussion between Mr Aldren, Mr Sila and representatives of UrbanX occurred on 20 December 2022 concerning branding and branding concepts, in which Mr Aldren said: “I don’t want to be associated with another brand, I don’t want someone else’s baggage – good or bad”, and “our main competitors will be Upstate, Cunninghams and Belle”. Mr Aldren expressed a preference for the name “The North Agency”, although Mr Argent had told him after looking at his mobile phone that someone else had registered that (presumably as a business name) but it was being de-registered and he would follow it up. Mr Aldren says, and I accept, that at no time during the meeting was the applicants’ business “The Agency” mentioned or discussed, nor was The Agency Group in his mind. In early January 2023, Mr Aldren double checked the website at www.business.gov.au and found that “The North Agency” was available. On 5 January 2023, Mr Aldren applied to register “The North Agency” as a business name.

37 On 24 January 2023 a further discussion occurred between Mr Aldren, Mr Sila and representatives of UrbanX. Various concepts were presented by UrbanX with concept 1 corresponding to the N Logo which was ultimately adopted. Mr Aldren says that he really liked the logo of concept 1 because it used the degree symbol and the “N” was like a compass point or arrow, picking up the theme of “The North”. Concept 3 employed black, grey, cream and white colouring, and a decision was made at that meeting to proceed with concept 1 with the colours and font of concept 3. Mr Sila says that the N Logo represented the letter N, together with the degree symbol reinforcing the “North” name and capturing the “true north” idea, which he thought looked good and would stand out among their competitors. Ms Nielson of UrbanX worked on the N Logo as a graphic designer, and gave evidence, which I accept, that she wanted to play on the location of the Northern Beaches using the idea of a compass. She also wanted to play on negative space by deleting the final stroke of the “N” in the icon, and she placed the degree symbol at the top of the deleted vertical line to represent pointing to the north. On 25 January 2023, UrbanX sent to Mr Aldren and Mr Sila the revised concept document called concept 4. Mr Aldren and Mr Sila then had a discussion in which they looked at the concept documents and the branding of other agencies on realestate.com.au and Domain. They decided that they would not use navy colouring because they did not want to look like the others, and decided that they would go with the charcoal colour as no one else on the Northern Beaches was using charcoal. They did not look at or consider The Agency Group or its website as part of that process. On 1 February 2023, UrbanX sent through by email a revised concept document called concept 5. On 6 February 2023, a further meeting between Mr Aldren, Mr Sila and representatives of UrbanX took place at their new office in Dee Why, and a decision was made that, as no one appeared to like the charcoal, they would go back to the navy colour.

38 From 6 February 2023, discussions took place concerning the website for the new business, to be known as The North Agency. Mr Aldren and Mr Sila wanted to have a location shot at the top of the website, similar to the one used in the brand concept documents with the logo over the top of the location shot. Mr Aldren engaged a photographer to do the photography for the website, including the location shot at the top of the website. Mr Aldren left it up to the photographer as to the shots that he should take. On about 21 February 2023, another meeting took place between Mr Aldren, Mr Sila and representatives of UrbanX in the Dee Why office. Everyone present agreed on the main shot for the website, being a shot of the ocean pool at Collaroy. No instruction was given to the photographer to take “twilight” shots, consistently with the way in which Mr Aldren has engaged that photographer over a number of years. Ms Nielson explained in her evidence that there are two ways to make text easily legible and stand out: one is to use a dark colour on a light background, and the other is to use a light colour on a dark background.

39 On 14 February 2023, a discussion took place between Mr Aldren, Mr Sila, representatives of UrbanX and Mr Shane Slater of Realtair, who is also an agent at The Agency Group’s Neutral Bay office. Realtair is a real estate software company. During that meeting Mr Slater asked what name they were going with, and when Mr Sila replied, “The North Agency”, Mr Slater responded: “It sounds a lot like The Agency.” Mr Aldren responded: “No, because we’re The North.” Nothing further was said about the name, and Mr Aldren says that he did not think that their name would be confused with The Agency Group. I accept that evidence, which was not challenged in cross-examination. Similarly, Ms Nielson’s evidence, which I accept, was that while she was aware of The Agency Group, she did not consider The Agency Group, their branding or their website at any time before or during the design process for The North Agency, and The Agency Group did not come up in any discussions.

40 In the first week of March 2023, the external signage for H.A.S. Real Estate’s new office at Dee Why was completed. In around mid-March the internal signage for the office was completed.

41 On or about 17 February 2023, representatives of UrbanX set up the Instagram account for The North Agency. The initial version was the navy colour of the branding of the new business and the current version is the cream colour of the branding and reflects the colour scheme of the external signage at the office. A short video was posted on the Instagram account on 2 March 2023, which displays prominently the N Logo. A Facebook page was also set up on or about 17 February 2023. Marketing materials were also developed and by mid-April, The North Agency had spent approximately $25,510 on branded material, including business cards, letter drop material, tear drop signs, clothes, merchandise, office folders, bidders’ cards and doormats.

42 The North Agency currently has six employees, comprising three sales consultants, a property manager, a head of operations and an executive assistant.

43 The effect of Mr Sila’s and Mr Aldren’s evidence is that at the time they were making arrangements and decisions for setting up their new real estate agency, they were aware of the existence of The Agency Group, however they did not look at The Agency Group’s website, and The Agency Group did not cross their minds at all in the process of deciding on the name or the branding for their new agency, including when they were considering their logo and their website. Neither of them intended to choose a name or branding which would cause any confusion with The Agency Group’s name or branding. On the contrary, they wished to differentiate themselves from other real estate agencies. At no time during the discussions involving Mr Aldren, Mr Sila and representatives of UrbanX about name and branding, did anyone mention The Agency Group (with the exception of the discussion with Mr Slater) until letters of demand preceding the present proceedings were sent. Both Mr Aldren and Mr Sila regarded their key competitors as being Cunninghams, Belle (Dee Why), Doyle Spillane and Upstate, and did not consider that The Agency Group was one of their key competitors. I accept all of that evidence, which was not challenged in cross-examination.

44 Both Mr Aldren and Mr Sila gave evidence, which I accept, as to industry practice in terms of attracting customers. Mr Aldren’s evidence is that in his experience, when a vendor wants to list their property, they list with an agent first and an agency second, because the relationship and trust with the individual agent is what is most important. In his experience, it is the agent, not the agency, who gets the listing for sale. It is also Mr Aldren’s experience that the decision as to which agent to engage is a big decision that is carefully considered by the vendor. Mr Aldren says that working for a known franchise or brand can assist an agent who is just starting out and does not have an existing reputation in the area, as the agent can also rely on the sales and reputation, in the area, of that known franchise or brand. All this is Mr Aldren’s experience across the real estate industry as a whole, and in particular on the northern beaches. As to contact with buyers, Mr Aldren is typically contacted or interacts with buyers in two major ways. First, a buyer, who has seen a property of interest on realestate.com.au or Domain, contacts Mr Aldren through the website or directly using the contact details on the website. Second, a buyer who comes to an open house inspection is required to provide a name and phone number before entering the property, and the buyer is then entered in the customer relationship management system and is followed up with a phone call or other communication. In Mr Aldren’s experience, a buyer usually comes to an open house inspection having seen the property advertised on realestate.com.au or Domain. In Mr Aldren’s experience, it is the property and the price, not the agent or agency, that causes a buyer to contact an agent or agency.

45 Mr Sila gave evidence, which I accept, concerning customers for property management services. The agreements and prospective agreements which H.A.S. Real Estate has with landlords have all come from previous clients or from referrals from previous clients to their friends or family members or people known by Mr Sila in the local community. In Mr Sila’s experience, apart from previous or existing clients and referrals, the main source of new management business is purchasers of properties which he has sold. In Mr Sila’s experience, it is the individual agent rather than the agency brand that primarily attracts listings. In his experience, prospective tenants generally come to him through the Domain or realestate.com.au websites, both of which have a tab entitled “Rent”, on which the user clicks and searches by the available search criteria which include “Suburb” or “Location” and “Property Type”. In his experience, having found potential rental properties on one or other of those websites, prospective tenants then email, call or text the agent with any queries about the properties and the rental application processes commence from there.

46 As to the importance of attracting customers in the real estate business by way of word of mouth, Mr Aldren accepts that that is an important means of attracting customers. However, in his experience, it is the agent, not the agency that secures a listing for sale, and it is the property and the price, not the agent or agency that causes a buyer to contact an agent or agency. I accept that evidence.

The Alleged Infringement of the Registered Marks

47 Under s 20 of the Trade Marks Act, the registered owner, being Ausnet, has the exclusive right to use and authorise the use of each of the Registered Marks in relation to the real estate services for which they are registered.

48 The applicants rely upon s 120(1) of the Trade Marks Act, which provides as follows:

A person infringes a registered trade mark if the person uses as a trade mark a sign that is substantially identical with, or deceptively similar to, the trade mark in relation to goods or services in respect of which the trade mark is registered.

49 Section 17 of the Trade Marks Act provides:

A “trade mark” is a sign used, or intended to be used, to distinguish goods or services dealt with or provided in the course of trade by a person from goods or services so dealt with or provided by any other person.

50 Subsection 7(5) defines “use of a trade mark in relation to services” as meaning “use of the trade mark in physical or other relation to the services”.

51 Section 10 defines “deceptively similar” as follows:

For the purposes of this Act, a trade mark is taken to be “deceptively similar” to another trade mark if it so nearly resembles that other trade mark that it is likely to deceive or cause confusion.

Use as a trade mark by the respondents

52 The first question which arises is whether the respondents have used “THE NORTH AGENCY” and the N Logo as trade marks. There cannot be any doubt that they have done so in much of their marketing material, such as their website, their use of the Domain and realestate.com.au websites, signboards, brochures and other printed material, merchandise and the fit-out of their office at Dee Why.

53 There is an issue as to whether the use of “thenorthagency” as the website URL or domain name, Facebook account and email addresses (or the use of “the.north.agency” in the Instagram account as their handle) is also use as a trade mark. The applicants also rely on the use of “The North Agency” on the Facebook page and the Instagram page of H.A.S. Real Estate. In Flexopack S.A. Plastics Industry v Flexopack Australia Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 235; (2016) 118 IPR 211 at [64]-[65], Beach J held that a domain name represents the respondent’s name which in turn functions as a trade mark, and a customer would not see the domain name as being merely descriptive as it is used to identify the website, which acts as “a virtual reality storefront offering the relevant goods for sale”. His Honour also held that the respondent in that case presented the domain name on company material, which was clearly to direct customers to the website and reinforced its indication of origin, and thereby the material used the domain name as a badge of origin to attract customers to the website featuring its goods. Similarly, in Goodman Fielder Pte Ltd v Conga Foods Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 1808; (2020) 158 IPR 9 at [140], Burley J held that a domain name of a company website represents a use as a trade mark in relation to the goods that the company website promotes, in that it is used to identify the website which promotes the goods listed in it for sale. His Honour held that the addition of the “www” prefix, and the suffix “.com.au”, did not substantially affect the identity of the trade mark under s 7(1) of the Trade Marks Act. Similarly, at [324]-[325] Burley J held that the use of words in the account name and the social media handle for a Facebook page and Instagram page amounted to uses of the words as a trade mark, in that a consumer would not see them as merely being descriptive, and they indicated a connection in the course of trade between the goods and the person who applied the mark to the goods. Similarly in the present case, I regard the use of “thenorthagency” in the domain name for the website of H.A.S. Real Estate, and also in the email addresses and similar terms in the social media account name and handle, as uses by H.A.S. Real Estate of that mark as a trade mark.

54 The word “agency” is plainly a description of the nature of a real estate agent’s business. However, the High Court said recently in Self Care IP Holdings Pty Ltd v Allergan Australia Pty Ltd [2023] HCA 8 at [25]:

The existence of a descriptive element or purpose does not necessarily preclude the sign being used as a trade mark. Where there are several purposes for the use of the sign, if one purpose is to distinguish the goods provided in the course of trade that will be sufficient to establish use as a trade mark. Where there are several words or signs used in combination, the existence of a clear dominant “brand” is relevant to the assessment of what would be taken to be the effect of the balance of the label, but does not mean another part of the label cannot also act to distinguish the goods.

Principles concerning deceptive similarity

55 Turning then to the question whether the use of those marks by H.A.S. Real Estate is deceptively similar to the Registered Marks, the High Court in Self Care has stated the relevant principles, which may be summarised as follows:

(a) the resemblance between the two marks must be the cause of the likely deception or confusion: [26];

(b) in the trade mark comparison, the marks must be judged as a whole taking into account both their look and their sound: [26];

(c) the marks should not be compared side by side: [27], [29];

(d) the effect of spoken description must be considered; if a mark is in fact or from its nature likely to be the source of some name or verbal description by which buyers will express their desire to have the goods (or services), then similarities both of sound and of meaning may play an important part: [27];

(e) the focus is upon the effect or impression produced on the mind of potential customers of the goods (or services) in relation to which the two marks are used and in the case of the registered mark, allowing for “imperfect recollection”: [28]-[29];

(f) the notional buyer is a person with no knowledge about any actual use of the registered mark, the actual business of the owner of the registered mark, the goods the owner produces, any acquired distinctiveness from the use of the marks prior to filing, or any reputation associated with the registered mark: [28];

(g) the correct approach is to compare the impression (allowing for imperfect recollection) that the notional buyer would have of the registered mark (as notionally used on all of the goods or services covered by the registration), with the impression that the notional buyer would have of the alleged infringer’s mark (as actually used): [29];

(h) “deceived” implies the creation of an incorrect belief or mental impression; “causing confusion” may merely involve “perplexing or mixing up the minds” of potential customers: [30];

(i) the usual manner in which ordinary people behave must be the test of what confusion or deception may be expected, having regard to the character of the customers who would be likely to buy the goods in issue: [31];

(j) it is not necessary to establish actual probability of deception or confusion, but a mere possibility of confusion is not enough. There must a real, tangible danger of deception or confusion occurring. It is enough if the notional buyer would entertain a reasonable doubt as to whether, due to the resemblance between the marks, the two products come from the same source. Put another way, there must be “a real likelihood that some people will wonder or be left in doubt about whether the two sets of products … come from the same source”: [32];

(k) evidence of actual confusion is of great weight, but not essential, and lack of such evidence may also be relevant: [30], [71]; and

(l) any intention to deceive or cause confusion may be a relevant consideration but is not required: [30].

56 A further issue dealt with by the High Court in Self Care requires lengthier treatment, and was the subject of able and measured submissions from both sets of counsel, for which I am most grateful. The High Court cited with approval a number of authorities which have held that material external to the respondent’s mark is irrelevant to the issue of deceptive similarity. In [29], footnotes 67 and 68 cite with approval the Full Court’s decision in MID Sydney Pty Ltd v Australian Tourism Co Ltd (1998) 90 FCR 236 at 245, in which Burchett, Sackville and Lehane JJ said that it is irrelevant that the respondent may, by means other than its use of the mark, make it clear that there is no connection between its business and that of the applicant, citing Mark Foy’s Ltd v Davies Coop & Co Ltd (1956) 95 CLR 190 at 205. On the same page, their Honours said that the comparison is between marks, not uses of marks, and hence it is no answer that the respondent’s use of the mark is in all the circumstances not deceptive, if the mark itself is deceptively similar.

57 Also at [29], in footnote 68 the High Court cited with approval Gummow J’s separate judgment in Wingate Marketing Pty Ltd v Levi Strauss & Co (1994) 49 FCR 89 at 128, in which his Honour said that in infringement proceedings the Court is concerned for practical purposes only with the two marks themselves, ignoring any matter added (in advertisements or on the goods) to the allegedly infringing trade mark. Accordingly, his Honour said that disclaimers are to be disregarded, price differential is irrelevant, differences in use by the parties of colour and display panels are disregarded, and differences in the respective sections of the public to whom the goods are sold should be discounted.

58 At [33], the High Court said that in considering the likelihood of confusion or deception, the Court is not looking to the totality of the conduct of the defendant in the same way as in a passing off suit. Footnote 81 to that proposition cites with approval a number of authorities, several of which expressly support the proposition that the essential comparison in an allegation of infringement is between the marks involved, and the addition of other matter by the respondent to its mark, or other aspects of the respondent’s conduct, are irrelevant: New South Wales Dairy Corporation v Murray-Goulburn Co-operative Co Ltd (1989) 86 ALR 549 at 589 (Gummow J); CA Henschke & Co v Rosemount Estates Pty Ltd (2000) 52 IPR 42 at [44] (Ryan, Branson and Lehane JJ); PDP Capital Pty Ltd v Grasshopper Ventures Pty Ltd (2021) 285 FCR 598 at [111] (Jagot, Nicholas and Burley JJ).

59 Having cited those authorities with approval, in support of well-established legal principle, the High Court was plainly not intending to overturn that principle. However, when the High Court came to apply the principles earlier stated to the question of confusion or deception, all five members of the Court at [70] referred to the relevant context as including advertising on the alleged infringer’s packaging and website saying, “prolong the look of Botox”, and then said at [70]:

In this case, the back of the packaging [of the product bearing the alleged infringing mark, PROTOX] stated in small font that “Botox is a registered trade mark of Allergan Inc” and, although the assumption is that Botox is an anti-wrinkle cream, the website stated that “PROTOX has no association with any anti-wrinkle injection brand”.

Further, at [71], having concluded that there was no real risk of confusion or deception, the High Court said unanimously:

That conclusion is reinforced by the fact that the PROTOX mark was “almost always used in proximity to the FREEZEFRAME mark” [that being a mark owned by the alleged infringer].

60 With the greatest respect, those passages are impossible to reconcile with the Court’s approval of the authorities referred to above which state that such additional material used by the respondent is irrelevant to the issue of trade mark infringement. The internal contradiction places a trial judge in an awkward dilemma, which I propose to resolve by simply disregarding the passages quoted above from [70] and [71] as unfortunate errors. On the High Court’s own reasoning, it would be a fundamental error of longstanding legal principle if I were to adopt their Honours’ mode of analysis in [70] and [71] by taking into account on the question of deceptive similarity, for example, that the use by H.A.S. Real Estate of “THE NORTH AGENCY” was typically accompanied by the distinctive N Logo, thereby implicitly disavowing any association with the applicants or their services.

61 On a separate matter, it is also relevant to note that it is not necessary to establish that confusion persists up to the point of sale, or that actual purchasers will ultimately be deceived: Southern Cross Refrigerating Co v Toowoomba Foundry Pty Ltd (1954) 91 CLR 592 at 595-6 (Kitto J).

62 In the case of a composite mark, the whole of the marks and devices, which may consist of a number of elements, must be considered in their context including the size, prominence and stylisation of words and device elements used in the mark and their relationship to each other, and any essential feature: Optical 88 Ltd v Optical 88 Pty Ltd (No 2) [2010] FCA 1380; (2010) 275 ALR 526 at [100]-[111] (Yates J); Australian Meat Group Pty Ltd v JBS Australia Pty Ltd [2018] FCAFC 207; (2018) 268 FCR 623 at [78] (Allsop CJ, Besanko and Yates JJ). As the Full Court said in the latter case at [78], to consider the mark otherwise would be to extend its scope well beyond the monopoly that has been granted by registration. In the case of a device logo mark, it is the combination of features that must be considered as a whole: Australian Meat Group at [71]. In comparing the two marks in that case, the Full Court considered all the visual features of the marks, including the arrangement and use of geometric elements, the orientation of each mark and its constituent parts, and the overall shape and stylistic impression of the marks: at [71]-[73] and [75]. Further, if words in a complex composite registered trade mark are too readily characterised as an “essential feature” of that mark in assessing the question of deceptive similarity, that may effectively convert a composite mark into something quite different: Crazy Ron’s Communications Pty Ltd v Mobileworld Communications Pty Ltd [2004] FCAFC 196; (2004) 61 IPR 212 at [100] (Moore, Sackville and Emmett J).

63 In comparing the marks to assess whether there is deceptive similarity, it is relevant to take into account the fact that the element of the mark that is common to both marks has been used by a number of traders and therefore must to some extent be discounted: Mond Staffordshire Refinery Co Ltd v Harlem (1929) 41 CLR 475 at 477-8; Wingate at 127 (Gummow J). In Self Care, the High Court at footnote 68 cited Wingate at 128 with approval. The relevant passage continues on p 129, at which the second of Gummow J’s particular propositions was that “evidence of trade usage, in the sense discussed above, is admissible but not so as to cut across the central importance of proposition (i)” (proposition (i) being that the comparison is between any normal use of the plaintiff’s mark comprised within the registration and that which the defendant actually does in the advertisements or on the goods in respect of which there is the alleged infringement, but ignoring any matter added to the allegedly infringing trade mark). The reference by Gummow J to evidence of trade usage “in the sense discussed above” was a reference to p 127 of his Honour’s judgment. In that way, the High Court in Self Care appears to have expressed approval of Gummow J’s analysis of the admissibility of evidence of trade usage at p 127. That is, evidence of trade usage is relevant to the assessment of deceptive similarity in relation to discounting an element of the marks that is commonly used by traders, but not in relation to defining the scope of actual use of the allegedly infringing mark for the purposes of comparison to the notional use of the registered mark.

The AGENCY Mark

64 In the application of those principles to the present case, the applicants made the following submissions. First, the applicants submitted that the impression or recollection to be carried away and retained by the notional consumer with an imperfect recollection of the AGENCY Mark is likely to be of its constituent words. Aurally, those constituent words make up the whole of the mark. Visually, the obvious function of the logo, being the stylised “A” element of the word AGENCY, is as the letter “A”. Reasonable and ordinary consumers, it is submitted, are highly unlikely to perceive and remember the mark as an unpronounceable device followed by the letters GENCY. The stylised “A” element is given no relevant prominence amongst the other letters, its size, font and vertical position are uniform and its horizontal position accords with the correct spelling of the word. The only difference in its stylisation is that the horizontal stroke of the letter “A” has been lowered from the middle to beneath the letter.

65 It is also submitted by the applicants, as to the impression upon the same notional consumer of THE NORTH AGENCY as actually used by H.A.S. Real Estate in plain and stylised forms, that the inclusion of NORTH alludes to the geographical location of the business of H.A.S. Real Estate on Sydney’s northern beaches. It is submitted that the addition of NORTH does not serve to distinguish competing providers of real estate services, rather it describes their location.

66 Next it is submitted that the real estate business is very much one of word of mouth, and is often conducted by telephone. It is argued that such aural usage of the marks is particularly relevant in this context. Further, due to the “word of mouth” nature of the market for real estate services, the word marks (including those in stylised form) are in fact likely to be the source of verbal description by which consumers will express their desire for such services. The applicants relied for that submission on Self Care at [51], which in turn approved the statement of Dixon and McTiernan JJ in Australian Woollen Mills Ltd v FS Walton & Co Ltd (1937) 58 CLR 641 at 658. Although the submission was expressed in terms of “word marks”, there are of course no word marks of the applicants in issue in the present proceedings, but I have treated that reference as intended to be a reference to the AGENCY Mark, on the one hand, and the name “THE NORTH AGENCY”, on the other hand. It is argued by the applicants that the similarities in sound and of meaning increase the likelihood of deception or confusion, by reference to Self Care at [27].

67 Finally, it is submitted that, at the very least, an ordinary consumer with an imperfect recollection of the notional use (throughout Australia, without geographical limitation) of the AGENCY Mark as a trade mark for real estate services is at risk of wondering, or being perplexed or mixed up, as to whether it might not be the case that real estate services provided by THE NORTH AGENCY might be a commercial extension, franchise or sub-brand of the AGENCY Mark, relying upon the judgment of Burchett J in Polo Textile Industries Pty Ltd v Domestic Textile Corporation Pty Ltd (1993) 42 FCR 227 at 230. The respondents submitted that that reasoning is inconsistent with the insistence by the High Court in Self Care that the reputation of the owner of the registered mark cannot be taken into account on questions of infringement. I do not accept that submission by the respondents. The notion of a brand being perceived as a commercial extension, franchise or sub-brand of the registered mark does not necessarily depend upon proof of the reputation of the registered owner. In Goodman Fielder at [344], Burley J said of the words “LA FAMIGLIA RANA” that many would consider in relation to that mark that the word “RANA” is an addition, connoting either a variant or sub-brand of “LA FAMIGLIA”, and there is no indication in the judgment that his Honour thought that the reputation of the registered owner was relevant.

68 In my view, there is a number of fundamental difficulties with those submissions and the allegation that H.A.S. Real Estate has used its marks in a way which is deceptively similar to the AGENCY Mark.

69 First, the insertion of the word “NORTH” in the mark “THE NORTH AGENCY” is a substantial differentiating feature from the AGENCY Mark which would remain in the minds of ordinary consumers with imperfect recollection. The addition of “NORTH” is not merely a reference to a geographical location, but also serves to distinguish a competing provider of real estate services. In much of the promotional material used by H.A.S. Real Estate, the words “THE NORTH” are larger and more prominent than the word “AGENCY”. However, that is not invariably the case, and the website URL, email addresses and social media handles use “thenorthagency” in a way which does not give any particular prominence to any aspect or aspects of that name. However, even in the latter case, I regard the use of the word “north” as a striking aspect of the mark which points strongly against any real likelihood of confusion. In my opinion, that reason alone is sufficient to undermine the applicants’ argument for infringement.

70 The second problem is that even if one takes into account the aural impression of “THE NORTH AGENCY” when spoken aloud, the use of “NORTH” is just as striking as in its written form. The stress would naturally fall on the word “NORTH” at least as much as the word “AGENCY”. That stress serves to emphasise the distinctive feature of the name used by H.A.S. Real Estate, and its emphasis on a specific geographic area as the focus of its business.

71 However, I do not regard any aural resemblance as a matter of particular significance in this case. In Self Care at [27] and [51], the High Court approved the statement of Dixon and McTiernan JJ in Australian Woollen Mills at 658 that similarities in sound and meaning may play an important part if a mark is in fact or from its nature likely to be the source of some name or verbal description by which buyers will express their desire to have the goods. However, in the present case, the effect of Mr Jensen’s evidence for the applicants is that online marketing is centrally important in the acquisition of real estate services, whether through the agency’s website (see his affidavit of 31 March 2023 at [22]) or through the Domain and realestate.com.au platforms (T54.17-32). This is not a case of sales over the counter in retail premises. Mr Jensen, Mr Aldren and Mr Sila all agreed that “word of mouth” is also important, but the evidence of all three stressed the importance of the connection with individual agents, rather than the agency. Moreover, as Mr Aldren said in his affidavit, it is the property (not the agent or agency) that causes a buyer to contact an agent or agency or attend a viewing of the property, typically after seeing the property on the realestate.com.au or Domain platform.

72 The third difficulty is that, as the Full Court said in Australian Meat Group, the whole of the marks and all of their elements must be considered. That includes the use of the stylised “A” conveying the idea of a house, which, in my view the ordinary consumer would not fail to recall. The AGENCY Mark is not a word mark, and the stylised “A” cannot be ignored in the comparison, as this Court made clear in Optical 88, Australian Meat Group and Crazy Ron’s. While there is no challenge to the registration of the AGENCY Mark under s 41 of the Trade Marks Act, and questions of registrability and infringement are distinct questions (see Self Care at [21]), it is relevant to take into account that the words “THE AGENCY” on their own have a strongly descriptive element in referring to the nature of a real estate business. The ordinary consumer would expect the word “agency” to be commonly used in the names of real estate businesses in Australia. It would give an unwarranted monopoly to The Agency Group if rival businesses were unable to use the definite article “The” and the word “Agency” in their business names. The ordinary consumer would not be confused by the fact that those words have been used by a rival trader, in light of their relatively high degree of descriptiveness of the nature of the business.

73 The applicants submitted that it was irrelevant to the question of trade mark infringement to consider whether elements of the Registered Mark were descriptive or relatively descriptive, submitting further that there was no issue in these proceedings as to registrability under s 41 of the Trade Marks Act. The applicants relied upon a passage in the judgment of the Full Court in Henley Constructions Pty Ltd v Henley Arch Pty Ltd [2023] FCAFC 62 at [167], in which Yates, Rofe and McElwaine JJ referred to the primary judge’s finding that HENLEY was not inherently distinctive as a trade mark but was nevertheless distinctive in fact of the respondent’s building and construction services. Their Honours said at [167] that those findings were highly relevant to the validity of the mark, but they were not “germane to the question of trade mark infringement and, in particular, to the assessment of deceptive similarity”. I do not read that statement as a statement of general principle to the effect that the relative lack of distinctiveness of a trade mark is irrelevant to the question of infringement and in particular to the assessment of deceptive similarity. Rather, I read that comment as a reference to the particular circumstances of that case. Three paragraphs later, at [170], their Honours dealt with a composite mark which incorporated the words HENLEY PROPERTIES and a triangular device. Their Honours commented that the primary judge had reasoned that in relation to this mark, the component HENLEY was emphasised considerably and that the component PROPERTIES, which was in smaller font underneath the HENLEY component, was descriptive of building and construction services. Their Honours said that they saw no error in that approach to determining the issues of deceptive similarity or in his Honour’s analysis. Accordingly, the Full Court accepted that it was relevant to take into account on questions of infringement that an element of a composite mark was descriptive. Further, in the earlier Full Court decision in Combe International Ltd v Dr August Wolff GmbH & Co KG Arzneimittel [2021] FCAFC 8; (2021) 157 IPR 230 at [76], McKerracher, Gleeson and Burley JJ said that it was not impermissible to consider whether the different elements of the rival marks in that case were descriptive on the question of deceptive similarity. Accordingly, in my opinion, these two Full Court authorities support the proposition that it is relevant to take into account on the question of deceptive similarity whether elements of the rival marks have a descriptive character. In my view, those authorities accord with common sense and the impressions which the ordinary consumer would form and retain.

74 Fourth, both the word “Agency” and a stylised roof or house device representing the letter “A”, are commonly used in business names and marks in the real estate industry. Ms Kennedy gave evidence of six other real estate agencies using the word “Agency” in their brand name, and five real estate agencies using a roof-shaped device, either in place of the letter “A” or beside its brand name. As discussed above, that evidence of trade usage is admissible on the question of infringement (insofar as a respondent seeks to discount an element in common between marks), and renders it even less likely that consumers would be confused by any resemblance between the AGENCY Mark and “THE NORTH AGENCY”, including any resemblance from the use of the word “Agency”.

75 Fifth, the context of these names being used in the real estate industry is important, in that the buying, selling and leasing of real property are among the most important transactions which ordinary consumers engage in during their lives. One comparator in the relevant enquiry is the consumer’s impression of the registered mark as notionally used on the goods or services covered by the registration, in this case real estate services. The other is the consumer’s impression of the allegedly infringing mark as actually used, in this case, again, in real estate services. One would expect a heightened sense of awareness and concentration among consumers in that context, compared to the degree of concentration and focus which would ordinarily be expected in more mundane, everyday transactions, such as the purchase of groceries or ordinary household items. While I accept that the question of confusion is not to be approached solely by reference to the ultimate point of entering into the transaction, and also extends to anterior stages of inducing interest in goods or services, I regard the heightened awareness and concentration of consumers as applying also at the early stages of a real estate transaction.

76 Sixth, as to the submission that an ordinary consumer might wonder whether the services provided by THE NORTH AGENCY might be a commercial extension, franchise or sub-brand of the AGENCY Mark, I do not regard that as a real risk. In addition to the reasons already given, I add the following. By the use of the definite article “THE”, before the word “AGENCY”, the AGENCY Mark conveys a claim to uniqueness among real estate agencies generally. It is akin to the use of the definite article in expressions such as the Harbour Tunnel or the Art Gallery. By placing an adjective between the definite article and the noun in the grammatically correct way, the meaning changes from a reference to uniqueness, to a reference merely to a particular member within the class referred to by the noun (for example, as in the south-bound Harbour Tunnel, or the old Art Gallery). It would obviously diminish the claim to uniqueness for the owner of that mark to promote its business simultaneously in a contradictory way as being no more than a particular agency within the general class of agencies. That would make no sense to the ordinary consumer. Accordingly, in my view, there is not a real risk of ordinary consumers wondering whether “THE NORTH AGENCY” is a commercial extension, franchise or sub-brand of the AGENCY Mark.

77 Accordingly, I do not regard the marks used by H.A.S. Real Estate as being deceptively similar to the AGENCY mark.

The Logo Mark

78 The N Logo and the Logo Mark are visually distinct. The N Logo is a stylised “N”, with the final vertical line of the “N” replaced by a degree symbol. The logo mark is an “A” with a horizontal line of the “A” dropped. Although both devices use two straight lines meeting at a peak, the orientation of those straight lines is clearly different. In the N Logo, the two lines form an asymmetrical shape, in that one line is vertical and the other line is in a diagonal orientation, joining to form a peak at the top left hand side of the device. In the Logo Mark the two lines form a symmetrical shape, the two straight lines both being in a diagonal orientation, each line joining to form a peak at the top in the centre of the device.

79 Further, the two devices convey different ideas. The N Logo, with the degree symbol, reinforces the words “THE NORTH” and a northerly direction. The degree symbol conveys the idea of a compass. It is not necessary to explore whether the ordinary consumer would also understand, as Mr Sila intended, that the logo would reflect the desirability of north-facing properties or the figurative expression of “finding one’s true north”, and I am inclined to think that those impressions are too subtle for the ordinary consumer to have formed. However, it is not necessary to go that far in order to conclude, as I do, that the N Logo conveys the strong impression of a northerly direction. By contrast, the Logo Mark conveys the impression of a house, with the two diagonal lines representing the roof.

80 In my opinion, there is no real, tangible danger or real likelihood of confusion occurring by reason of any limited resemblance which may exist between the two devices.

81 I note also that, while it is not necessary to adduce such evidence, there is no evidence of any consumer having been confused. Nor is it necessary to adduce evidence of any intention on the part of the alleged infringer to confuse, however I note that the unchallenged evidence in the present case is to the contrary effect.

The Defence under s 122(1)(b)

82 In light of the view which I have formed on the question of deceptive similarity, it is not necessary to consider the defence relied upon by the respondents of having used in good faith a sign to indicate the description of the services, within the meaning and scope of s 122(1)(b) of the Trade Marks Act. There is no question about the subjective good faith of the respondents, and there was no challenge to the evidence of Mr Aldren that he believed it was important for the name of the business to describe what the business does and that was the reason for selecting the word “Agency”, or the evidence of Mr Sila that he considered the “Agency” component as describing their real estate business.

83 However, there are two difficulties with this defence. First, it has been held that a trader who uses a sign to distinguish its goods or services in the course of trade from those of another trader will not have used the sign “purely for the purposes of description”: FH Faulding & Co Ltd v Imperial Chemical Industries of Australia and New Zealand Ltd [1965] HCA 72; (1965) 112 CLR 537 at 543-4 (McTiernan J, whose reasoning on the point was not relevantly disturbed on appeal); Angoves Pty Ltd v Johnson [1982] FCA 119; (1982) 43 ALR 349 at 354 (Franki J) and 375 (Fitzgerald J). In the present case, it could not be said that the respondents have used “THE NORTH AGENCY” purely for the purposes of description, as they have also used those words for the purpose of distinguishing their services in the course of trade from those of other traders.

84 Second, the requirement of good faith is not satisfied merely by proving the absence of fraud or conscious dishonesty: Anheuser-Busch v Budejovicky Budvar [2000] FCA 390; 56 IPR 182 at [217] (Allsop J). There is also a requirement of reasonable diligence to ascertain that a chosen name does not conflict with a registered trade mark: Flexopack at [116] (Beach J). As Beach J held in that case, the objective requirement of reasonable diligence would require a search of the Register of Trade Marks: at [150]. Although Mr Aldren was aware of The Agency Group’s office in Manly by mid-2022, and both he and Mr Sila were aware of the brand “The Agency”, no search was conducted of the Register of Trade Marks to ascertain what marks had been registered.

85 Accordingly, if the question had been necessary to decide, then I would not have upheld the respondents’ defence of use in good faith under s 122(1)(b).

Misleading or deceptive conduct and passing off

The Applicants’ Allegations

86 In their concise statement at paragraphs 15-18, the applicants allege that:

(a) by reason of its long and widespread use and promotion of the Registered Marks and associated get-up in relation to its real estate services, both nationwide and particularly in and around the Northern Beaches region, The Agency Group has established a substantial reputation and goodwill in the Registered Marks and associated get-up;

(b) by their conduct, the respondents have falsely represented to consumers that they and/or their real estate services are affiliated with and/or authorised by the applicants;

(c) the respondents were aware of the success of The Agency Group and the Registered Marks and associated get-up yet deliberately chose to adopt trade marks and associated get-up “sailing close to the wind” of the Registered Marks and associated get-up; and

(d) in the circumstances, the respondents have:

(i) engaged in conduct which is misleading or deceptive or is likely to mislead or deceive in contravention of s 18 of the ACL;

(ii) made false or misleading representations in contravention of s 29(1)(g), (h) and/or (k) of the ACL; and

(iii) committed the tort of passing off.

The allegation in (c) above concerning “sailing close to the wind” was abandoned by the applicants during final addresses: T163.19-30.

Legal Principles

87 In Self Care, the High Court set out some well-established principles concerning ss 18 and 29 of the ACL. They are relevantly as follows:

(a) determining whether a person has breached s 18 of the ACL involves four steps: first, identifying with precision the “conduct” said to contravene s 18; second, considering whether the identified conduct was conduct “in trade or commerce”; third, considering what meaning that conduct conveyed; and fourth, determining whether that conduct in light of that meaning was “misleading or deceptive or … likely to mislead or deceive”: [80];

(b) the third and fourth steps require the court to characterise, as an objective matter, the conduct viewed as a whole and its notional effects, judged by reference to its context, on the state of mind of the relevant person or class of persons. That context includes the immediate context (relevantly, all the words in the document or other communication and the manner in which those words are conveyed, not just a word or phrase in isolation) and the broader context of the relevant surrounding facts and circumstances: [82];

(c) where the conduct was directed to the public or part of the public, the third and fourth steps must be undertaken by reference to the effect or likely effect of the conduct on the ordinary and reasonable members of the relevant class of persons. This avoids using the very ignorant or the very knowledgeable to assess the effect or likely effect; it also avoids using those credited with habitual caution or exceptional carelessness; it also avoids considering the assumptions of persons which are extreme or fanciful: [83]; and

(d) although s 18 takes a different form to s 29, the prohibitions are similar in nature and in the Self Care appeal there was no relevant meaningful difference between the words “misleading or deceptive” in s 18 and “false or misleading” in s 29: [84]. In the present case, neither party suggested any relevant difference between those two provisions.

88 For the purposes of the present case, the following principles are also relevant. First, conduct is, or is likely to be, misleading or deceptive if it has a tendency to lead into error: ACCC v TPG Internet Pty Ltd [2013] HCA 54; (2013) 250 CLR 640 at [39] (French CJ, Crennan, Bell and Keane JJ).

89 Second, the threshold “likely to be” is satisfied where there is a real and not remote possibility that conduct will mislead or deceive: ACCC v Employsure Pty Ltd [2021] FCAFC 142; (2021) 392 ALR 205 at [89] (Rares, Murphy and Abraham JJ).

90 Third, the respondents place particular reliance on a passage from the judgment of Stephen J (with whom Barwick CJ and Jacobs J agreed, as also did Aickin J by reason of having agreed with the reasons of Barwick CJ) in Hornsby Building Information Centre Pty Ltd v Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd (1978) 140 CLR 216 at 229, dealing with a case in which Sydney Building Information Centre Ltd sought an injunction restraining a company from carrying on business under the name “Hornsby Building Information Centre” on the ground of misleading or deceptive conduct pursuant to the then ss 52 and 80 of the Trade Practices Act 1974 (Cth). In that passage, Stephen J said:

There is a price to be paid for the advantages flowing from the possession of an eloquently descriptive trade name. Because it is descriptive it is equally applicable to any business of a like kind, its very descriptiveness ensures that it is not distinctive of any particular business and hence its application to other like businesses will not ordinarily mislead the public. In cases of passing off, where it is the wrongful appropriation of the reputation of another or that of his goods that is in question, a plaintiff which uses descriptive words in its trade name will find that quite small differences in a competitor’s trade name will render the latter immune from action …. The risk of confusion must be accepted, to do otherwise is to give to one who appropriates to himself descriptive words an unfair monopoly in those words and might even deter others from pursuing the occupation which the words describe.

At 230, Stephen J said that the case of statutory misleading conduct was a fortiori. His Honour said:

To allow this section of the Trade Practices Act to be used as an instrument for the creation of any monopoly in descriptive names would be to mock the manifest intent of the legislation.

91 As to the elements of the action for passing off, these were set out by O’Bryan J in Urban Alley Brewery Pty Ltd v La Sirene Pty Ltd [2020] FCA 82; (2020) 150 IPR 11 at [235] by reference to an abundance of authority as follows:

(a) a reputation in the get-up of the plaintiff’s products such that the get-up is recognised by relevant purchasers as distinctive of the plaintiff’s products;

(b) a misrepresentation (whether intentionally or unintentionally) by the defendant’s use of the same or a similar get-up to indicate that the defendant’s products are the same as the plaintiff’s products or come from the same source; and

(c) damage flowing from the erroneous belief engendered by the misrepresentation.

92 O’Bryan J at [236] referred to there being a presumption of damage upon proof of the first two elements. It was accepted by Mr Heerey KC that such a presumption is rebuttable: T203.6-13.

Application of the Legal Principles

93 In the first place, I accept the applicants’ submission that they have established a substantial reputation and goodwill in the Registered Marks and much of the associated get-up. I have referred already to the evidence as to the volume of sales and listings of The Agency Group, together with substantial advertising expenditure and other promotions. The reputation exists throughout Australia and most relevantly throughout New South Wales in the regions of the 21 physical locations in which its agents operate. That reputation exists in the Northern Beaches area which is served by two offices of The Agency Group (being Neutral Bay and Manly), and there is a number of other offices which are reasonably proximate to that region. I have also referred above to the evidence as to use by The Agency Group since 2017 of the Registered Marks, including the use of those marks on its own website and on other real estate and social media platforms.

94 Those marks are often displayed in a way which is contrasted against the relative darkness of their backgrounds, such as in photography of properties or aerial views of broader locations taken at dusk. Mr Jensen admitted in cross-examination that the current form of the home page on the applicants’ website, that includes images with a dark sky at dusk, has only been used by the applicants since some (unidentified) time after January 2023: T63.40-41. I also accept the respondents’ submission that it is very common for real estate services to use images of properties with a dark sky at dusk (T174.13-14). The evidence is insufficient for me to say that the period of exposure to the public is long enough to establish a substantial reputation in that particular get-up.

95 As to the relevant section of the public for the purpose of assessing the effect of the respondents’ conduct, the relevant class consists of consumers of real estate agency services in Australia, not limited to those who already live in the Northern Beaches region of Sydney. The evidence of Mr Aldren and Mr Sila in cross-examination established that:

(a) people move all the time to come and live in the Northern Beaches from other parts of Sydney and interstate;

(b) the Northern Beaches is a popular place for people looking for a sea change and retirees, particularly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic;

(c) the respondents also deal with landlords who own properties in the Northern Beaches but who live elsewhere, such as other parts of Sydney and other states such as Victoria and Queensland;

(d) the respondents are capable of selling real estate some distance from their office and have done so previously; and

(e) accordingly, when selling a house in the Northern Beaches, they adopt a strategy that does not limit their advertising campaign to that locality because they want to appeal to potential purchasers outside that area, from all over Sydney, New South Wales and as far as Western Australia.

96 The real question in relation to these allegations is whether the brand and get-up used by H.A.S. Real Estate in all of the circumstances was misleading or deceptive or likely to mislead or deceive. The applicants allege that the brand and get up of H.A.S. Real Estate, in the context of all relevant surrounding facts and circumstances, creates an overall impression of similarity with those of The Agency Group that gives rise to an objectively real and not remote possibility of consumers being misled or deceived. The applicants point to the evidence that since early March 2023, H.A.S. Real Estate has promoted a real estate agency business using get-up featuring the name “THE NORTH AGENCY” in white block capitals and the N Logo against a dark background, particularly including a dark sky at dusk. The applicants say that is exemplified by the evidence from its website, which I have extracted above.

97 In my view, the conduct of H.A.S. Real Estate is neither misleading or deceptive, nor likely to mislead or deceive, nor does it constitute passing off. It does not have a tendency to lead the relevant section of the public into error and in my view there is not a real possibility that the relevant conduct will mislead or deceive. In my view, the conduct of H.A.S. Real Estate does not give rise to a representation to the relevant consumers that it or its real estate services are affiliated with or authorised by the applicants. I reach those conclusions for the following reasons.