A survey on zoo mortality over a 12-year period in Italy

- Published

- Accepted

- Received

- Academic Editor

- David Roberts

- Subject Areas

- Conservation Biology, Veterinary Medicine

- Keywords

- Mammals, Mortality, Pathology, Zoo animals

- Copyright

- © 2019 Scaglione et al.

- Licence

- This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. For attribution, the original author(s), title, publication source (PeerJ) and either DOI or URL of the article must be cited.

- Cite this article

- 2019. A survey on zoo mortality over a 12-year period in Italy. PeerJ 7:e6198 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6198

Abstract

Background

The zoo is a unique environment in which to study animals. Zoos have a long history of research into aspects of animal biology, even if this was not the primary purpose for which they were established. The data collected from zoo animals can have a great biological relevance and it can tell us more about what these animals are like outside the captive environment. In order to ensure the health of all captive animals, it is important to perform a post-mortem examination on all the animals that die in captivity.

Methods

The causes of mortality of two hundred and eighty two mammals which died between 2004 and 2015 in three different Italian zoos (a Biopark, a Safari Park and a private conservation center) have been investigated.

Results

Post mortem findings have been evaluated reporting the cause of death, zoo type, year and animal category. The animals frequently died from infectious diseases, in particular the causes of death in ruminants were mostly related to gastro-intestinal pathologies. pulmonary diseases were also very common in each of the zoos in the study. Moreover, death was sometimes attributable to traumas, as a result of fighting between conspecifics or during mating. Cases of genetic diseases and malformations have also been registered.

Discussion

This research was a confirmation of how conservation, histology and pathology are all connected through individual animals. These areas of expertise are extremely important to ensure the survival of rare and endangered species and to learn more about their morphological and physiological conditions. They are also useful to control pathologies, parasites and illnesses that can have a great impact on the species in captivity. Finally, this study underlines the importance of a close collaboration between veterinarians, zoo biologists and pathologists. Necropsy findings can help conservationists to determine how to support wild animal populations.

Introduction

Zoos have always been considered as establishments where wild animals are kept for exhibition (other than a circus or a pet shop) to which members of the public have access, with or without charge for admission, for a minimum period of seven calendar days per year (Hosey, Melfi & Pankhurst, 2009). Many zoos around the world keep animals confined to small spaces compared to their wide-ranging peers in the wild. Due to spatial constraints captive environments have difficulty in providing the ideal setting for natural behaviour, such as hunting, resulting in welfare issues among captive animals (Morgan & Tromborg, 2007). Sometimes, animals in captivity exhibit abnormal behaviour such stereotypies (Vaz et al., 2017) or aggressiveness (Salas et al., 2016) due to poor welfare, as behaviour is an animal’s “first line of defence” in response to environmental change, i.e., what animals do to interact with, respond to, and control their environment (Mench, 1998). Moreover, in literature, the pathologies affecting captive animals have been shown to be different from the ones affecting wild populations (Seeley et al., 2016; Strong et al., 2016).

Fortunately today, the concept of zoo has changed. Many associations cooperate together to give a new point of view about zoos. It is important to highlight that zoos are not simply cages in which animals are kept prisoner, as many people believe. They should be valued for their aims and goals. One of the key goals of many captive management programs is the eventual reintroduction of species back into the wild. Zoos exhibit species to educate the public and cultivate its appreciation of conservation or research programs. Zoos offer their visitors “edu-trainment” through shows, contact areas, and interactive exhibits. They also begin to reflect on the reason for their existence , along with issues related to animal welfare, such as behavior, exhibit design, and nutrition (Griffin, 1992).

There are many types of modern zoos: safari parks, conservation centers, landscape immersions, ecosystem exhibits, as well as bioparks and sustainable zoos. Research, education and conservation are functions which, in the last one hundred years or so, have been grafted onto the recreational rootstock of zoos (Robinson, 1989).

Keeping wild animals in captivity has advantages, first of all, for animals (conservation can be viewed as beneficial for populations of animals, if not always for individual animals kept in captivity) and for humans as well (education, conservation, recreation and scientific discovery). Wild animals in captivity may not necessarily experience negative welfare and may, in some cases, be better off than they would be in the wild (Bostock, 1993).

Conservation of endangered species is now one of the major goals of accredited zoos. The emphasis on a conservation role for zoos grew greatly in importance during the 1970s and 1980s, prompted partly by the zoos themselves and partly by external pressures, such as new international treaties and national legislation (Hosey, Melfi & Pankhurst, 2009). Another important aspect related to conservation is biodiversity.

Today, the term “conservation” and “biodiversity” are often used together, to make explicit the distinction between the conservation of living organism and non-living structures, such as buildings or books (Hosey, Melfi & Pankhurst, 2009). Another way of defining biodiversity would be as the sum total of genes, species and ecosystem in a region (WRI/IUCN/UNEP/FAO/UNESCO, 1992). The role of the zoo in the conservation of biodiversity can be defined in four general areas:

-

maintenance of captive stocks of endangered species; this is the idea of zoo that can act as a kind of ‘ark’;

-

support for, and practical involvement with, in situ conservation projects. Zoos could contribute to this with, amongst other things, animal planning expertise, infrastructure, and financial support;

-

education and campaigning about conservation issues; this can be achieved through enclosure design, signage, keeper talks, interactive education, animal shows... Indeed, it is as important sometimes to keep species of low conservation importance in zoos as it is to keep the high-priority species, because they may be more useful in promoting the conservation message by enhancing people’s experience of animals at the zoo;

-

research that benefits the science and practice of conservation; for many years, research conducted on zoo animals tended to be concerned primarily with anatomy and taxonomy, but there is a huge potential in zoo to undertake behavioral, genetic, and physiological research that contributes to the in situ and ex situ conservation of endangered species (Ryder & Feistner, 1995).

These roles and activities have been pointed out in three documents: “The World Zoo Conservation Strategy” (IUDZG/CBSG, 1993), “The World Zoo and Aquarium Conservation Strategy” (WAZA, 2005) and “Turning the Tide” (Hosey, Melfi & Pankhurst, 2009; WAZA, 2009).

The zoo is a unique environment in which to study animals. Unlike in the wild, the animals are easily accessible to the researcher, so within the framework of structured research and with the correct licenses, data from zoo animals can be collected which would otherwise be very difficult to get from their wild counterparts from a logistical point of view. Furthermore, unlike in the wild, some manipulations may be possible in the zoo to take research beyond the purely observational and into experimental approaches (Hosey, Melfi & Pankhurst, 2009), even if some data might be biased by captivity (i.e., behavior, hunting).

Zoos have a long history of research into aspects of animal biology, even if this was not the primary purpose for which they were established (Hutchins, 2001).

The data collected from zoo animals can have a greater biological relevance than data obtained from the laboratory, and it can tell us more about what these animals are like outside the captive environment (Hosey, Melfi & Pankhurst, 2009).

As a consequence, many zoos carry out their research in collaboration both with other zoos and with other bodies, such as universities and conservation agencies. Indeed, universities and zoos can complement each other, for example on topics such as the control and analysis of behavior, conservation of endangered species, the education of students and the general public (Fernandez & Timberlake, 2008). One of the greatest examples of the importance of research in zoo animals is the discovery and management of diseases.

Diseases may be ‘of concern’ to zoos either because of the direct risk of animal loss or because of the impact on the zoo of required measures in the case of an outbreak.

Each zoo will have different ‘diseases of concern’, depending on its geographical location and the types of animal in its collection, which may vary quite widely from collection to collection, and over time.

Diseases can be considered under four broad headings for all zoos:

-

infectious diseases;

-

degenerative diseases;

-

genetic diseases;

-

nutritional diseases (Hosey, Melfi & Pankhurst, 2009).

Furthermore capture, restraint, and anesthesia are also stressful procedures for animals, and particularly so for wild species. It may be better to leave an animal with a superficial injury to heal on its own without treatment if the only alternative is capture and full anesthesia. Veterinary treatment may have adverse effects on an animal’s reproductive status, or may result in aggression from conspecifics when an individual is removed for treatment and then returned into a social group. Medication that can be administered in food or drinking water may be an option when capture and injection of drug is not desirable from a welfare perspective, or when it would put veterinary staff or keepers at high risk of injury. Euthanasia is also an option (Hosey, Melfi & Pankhurst, 2009).

Preventive medicine and care play a very important role in zoos. The preventive medicine program for captive wild animals includes: stock selection, quarantine, routine health monitoring and maintenance, enclosure design, pest control, sanitation, and an employee health program. The overall goals of a preventive medicine program are to prevent disease from entering the animal collection, to ensure that the animals are properly maintained, and to avoid dissemination of diseases to other institutions, or to free-ranging populations if collection animals belong to a reintroduction program (Norton, 1993).

Preventive medicine often starts with the careful selection of new animals and a period of quarantine or isolation.

In order to protect the health of all captive animals, it is important to perform a post-mortem examination on all the animals that die in the collection and also on wild and feral animals found dead on the zoo grounds (Hosey, Melfi & Pankhurst, 2009). Many Species Survival Plans (SSPs) have extensive necropsy protocols, so the appropriate SSP Veterinary Advisor should be consulted in advance for this information (Silberman, 1988).

Proper disposal of animal carcasses is essential for both human and animal health, as well as to comply with local and federal regulations (Hinshaw, Amand & Tinkelman, 1996).

Long-term post-mortem records provide useful data on trends in health, both for individual zoos and among the wider zoo community, and this information can then help future decisions about health care in living animals.

The aim of the study was to evaluate the mortality causes, to highlight the importance of post-mortem examination and its role in preventive medicine and, secondly, to consider the importance of the veterinarian collaboration and cooperation between zoological gardens.

There are potential criticisms to this paper. Due to privacy policies, there is a lack of data regarding the animal inventory in relation to the number of necropsies. The authors are not allowed to report the data regarding the number of new animals arriving in the zoo, the number of births, the number of animals sent to other zoos, and this all influences the number of dead animals.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection

The study on the causes of death in zoo animals was performed taking into account the years from 2004 and 2015. It was decided to focus on the Order of mammalians only, which has been divided into four categories: monogastric herbivores, ruminants, carnivores and omnivores. Two hundred and eighty two necropsies were carried out.

The animals came from three different Italian zoos (a Biopark, a Safari Park and a private conservation center) and were referred to the Department of Veterinary Science of the University of Turin (Italy).

Sample analysis

Necropsy examination was performed for each animal by two pathologists. A file was filled in with the following fields: assigned number, autopsy date, zoo of origin, species, sex, age, sampled organs.

Gross examinations were performed for each animal. Based on the macroscopic findings, the pathologists sampled organs for the histological and/or microbiological investigations.

The organs were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for histological examination. The samples were paraffin-embedded and sections of 4 µm were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Histochemical or immunohistochemical staining was performed, if necessary. All possible differential diagnoses were taken into account. Bacteriological, virological and parasitological investigations were performed, if needed.

Macroscopical and/or microscopic findings were classified according to the cause of death, including spontaneous pathology, infectious, genetic, complications (e.g., anesthesiological and surgical problems, management) and other causes (e.g., degenerative, neoplasia, nutritional and not determined diseases).

Statistical analysis

The resulting data were analyzed by GraphPad Prism (vers. 6.0; GraphPad Software, California, USA). The association between the different tested variables was assessed by χ2 Test. All results were considered statistically significant with the value p < 0.05.

Results

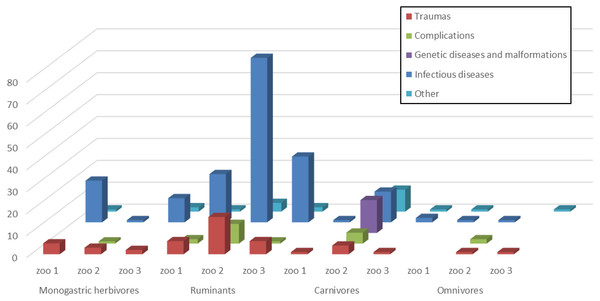

In Table 1 and Fig. 1, the total number of dead animals and their causes of death in the three different zoos is summarized.

| Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| zoo 1 | zoo 2 | zoo 3 | zoo 1 | zoo 2 | zoo 3 | zoo 1 | zoo 2 | zoo 3 | zoo 1 | zoo 2 | zoo 3 | ||

| Infect. diseases | 19 | 1 | 11 | 22 | 75 | 30 | 1 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 177 | |

| Traumas | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 17 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 47 | |

| Complications | 1 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 20 | ||||||

| Genetic diseases and malformations | 15 | 15 | |||||||||||

| Other | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 23 | |||

| Tot. | 25 | 5 | 15 | 31 | 105 | 39 | 2 | 48 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 282 |

Figure 1: Causes of death in the three different zoos.

Dead animals classified according to their digestive system and their causes of death in the three different zoos.Animals were classified according to their digestive system, with reference to the three zoos. Out of the 282 dead animals, 45 were monogastric herbivores, 175 were ruminants, 54 carnivores, and eight of them were omnivores.

A statistically significant association (P < 0.01) between the zoo and the category of animals was detected.

Animals were analyzed separately according to the provenance from the various zoos, and they were classified on the basis of their digestive system and the cause of death. A statistically significant association has been revealed between the category of dead animals and the three zoos (p < 0.0001). Moreover, when the zoos were considered together, a statistically significant association was also revealed between the category of dead animals and the cause of death (p < 0.0001).

In Zoo 1 out of the 60 dead animals, 25 (41.7%) were monogastric herbivores and 19 (76%) of them died from infectious diseases. Out of 31 (51.7%) ruminants, 22 (71%) died from infectious diseases. In Zoo 2, out of 162 dead animals, 105 (64.8%) were ruminants, and 75 (71.4%) died from infectious diseases, as well as 14 (29.2%) of the 48 (29.6%) carnivores. Fifteen (31.2%) carnivores died from genetic diseases or malformations and 5 (10.4%) from complications. In Zoo 3, of 60 dead animals, 30 (76.9%) of the 39 (65%) ruminants and 11 (73.3%) of the 15 (25%) monogastric herbivores died from infectious diseases.

In Zoo 1, the highest level of mortality was found in 2013, when 15 animals died (25%) and of them, 12 (80%) died from infectious diseases.

In 2015, 12 deaths were registered (20%) and of these 10 (83.3%) were from infectious diseases. Out of the 15 animals which died in 2013 in Zoo 1, 7 (46.7%) were monogastric herbivores and 7 (46.7%) were ruminants (Table 2).

| infect. disease | Traumas | Complication | Genetic diseases and malformation | Other | Total | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | ||

| 2005 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2006 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2007 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||||||||||||

| 2008 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2009 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2010 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2011 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2012 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2013 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 15 | |||||||||||||||

| 2014 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 12 | ||||||||||||||||

| Totale | 19 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 43 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 60 |

In 2015, out of the 12 deaths registered, 5 (41.7%) were represented by monogastric herbivores and 7 (58.3%) by ruminants. In Zoo 2 mortality was particularly high in 2009, with 32 (19.7%) deaths, 25 of which (78.1%) from infectious disease.

The most significant years for mortality in Zoo 2 were from 2006 to 2010, and involved mostly carnivores and ruminants (Table 3).

| infect. disease | Traumas | Complication | Genetic diseases and malformation | Other | Total | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | ||

| 2004 | 12 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 19 | ||||||||||||||

| 2005 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 10 | ||||||||||||||

| 2006 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 20 | |||||||||||||

| 2007 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 15 | ||||||||||||

| 2008 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 22 | ||||||||||

| 2009 | 23 | 2 | 25 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 32 | |||||||||||||

| 2010 | 13 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 18 | |||||||||||||||

| 2011 | 7 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 14 | |||||||||||||

| 2012 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 10 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2013 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2014 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Totale | 1 | 75 | 14 | 1 | 91 | 3 | 17 | 4 | 1 | 25 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 0 | 14 | 162 |

The highest mortality in Zoo 3 was in 2004, with 39 (65%) deaths.

Among them, 29 (74.3%) died from infectious disease. In 2005 19 (31.7%) deaths were registered and 12 (63.1%) of them were attributable to infectious diseases.

In Zoo 3 in 2004, out of the 39 (65%) dead animals, 29 (74.3%) were ruminants and 7 (17.9%) were monogastric herbivores. In 2005, of 19 (31.7%) dead animals 10 (52.6%) were ruminants, 7 (36.8%) were monogastric herbivores, and 2 (10.5%) carnivores (Table 4).

Neoplasia, degenerative, nutritional and not determined diseases were classified as “other” in all the zoos, since some pathologies were not clearly ascribable to a specific cause (e.g., when hepatic failure occurred as a result of steatosis the primary cause of this disease could be attributable both to degenerative or a nutritional factor).

Post-mortem findings in zoos

The results obtained from laboratory investigations performed on animal death in the three zoos are reported in Tables 5–7.

Discussion

After the death of an animal, zoos are always advised to perform post-mortem examinations. The responsibility for this decision normally lies with the zoo veterinarian. Fast retrieval, storage and disposal of the carcass, contact with a specialized pathologist and record keeping are good practices to facilitate the high quality of post-mortem examinations. The safety of the staff in contact with dead animals is also relevant for inclusion in the protocol for post-mortem procedures (EU Zoo Directive, 2015).

The cause of death for each animal dying in the collection needs to be established where reasonable and practicable to do so, including, in the majority of cases, the examination of the specimen by a veterinary surgeon, pathologist or practitioner with relevant experience and training (EAZA, 2014). Often parasites, nutritional deficiencies, or dental disease, may be present in the animal collection without causing any obvious symptoms or clinical signs. Their detection at post-mortem examination frequently indicates that diagnostic tests or treatments should be performed on the remaining animals before clinical symptoms or disease transmission occur (Defra, 2012).

In this survey a general analysis has been reported, conducted by a group of veterinary pathologists, on the most common causes of death in zoo animals, over a twelve-year period. In order to provide complete and satisfactory data, 282 necropsies of zoo animals were performed.

Three different types of zoo were included in the study (a Biopark, a Safari Park and a private conservation center) as each of these zoos had a different approach to the idea of zoo animal husbandry, as described in the introduction.

| Infect. disease | Traumas | Complication | Genetic diseases and malformation | Other | Total | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | Monogastric herbivores | Ruminants | Carnivores | Omnivores | Total | ||

| 2004 | 6 | 23 | 29 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 39 | |||||||||||

| 2005 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 19 | |||||||||||||

| 2006 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Totale | 11 | 30 | 2 | 0 | 43 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 60 |

| Register number | Year | Species | Causes of death | Lab. findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | 2005 | Horse | Septicemia | C.perfrigens type D |

| 2A | 2005 | Skunk | Pulmonary emphysema | – |

| 3A | 2006 | Fallow deer | Trauma | – |

| 4A | 2006 | Fallow deer | Toxemia syndrome | – |

| 5A | 2006 | Ilama | Pneumonia | – |

| 6A | 2007 | Goat | Aspiration pneumonia | – |

| 7A | 2007 | Grey squirrel | Trauma | – |

| 8A | 2007 | Deer | Trauma | – |

| 9A | 2007 | Goat | Pneumonia | |

| 10A | 2007 | Patagonia hare | Septicemia | Pseudotuberculosis |

| 11A | 2008 | Ilama | Pneumonia | – |

| 12A | 2008 | Ilama | Pneumonia | – |

| 15 a | 2008 | Patagonia hare | Septicemia | – |

| 13A–14A | 2008 | Domestic rabbits | Pneumonia | – |

| 16A | 2009 | Siberian tiger | Internal hemorrhage | – |

| 17A | 2010 | Tibetan goat | Clostridial enterocolitis | Clostridiosis |

| 18A | 2010 | Hare | Trauma | |

| 19A | 2010 | Tibetan goat | Septicemia | E.coli |

| 20A | 2011 | Ilama | Septicemia | Salmonellosis |

| 21A | 2011 | Antelope | Pleuritis | – |

| 22A | 2012 | Antelope | Septicemia | – |

| 23A | 2012 | Deer | Cranial trauma | – |

| 24A | 2012 | Deer | Septicemia | Actinobacillosis |

| 25A | 2012 | Hare | Trauma | – |

| 26A | 2012 | Swine | Pericarditis | – |

| 27–31A | 2012 | Hares | Pneumonia | – |

| 32A | 2013 | Deer | Septicemia | Enterococcus |

| 33A | 2013 | Ilama calf | Pneumonia | – |

| 34–35A | 2013 | Eulemurs | Trauma | – |

| 36A | 2013 | Hare | Septicemia | Pasteurella multocida |

| 37–40A | 2013 | Rabbits | Pneumonia | – |

| 41A | 2013 | Siberian tiger | Pulmonary hemorrhage | – |

| 42–43A | 2013 | Mohr gazelles | Pneumonia | – |

| 44A | 2013 | Thompson gazelle | Dystocia | – |

| 45–46A | 2013 | Deer | Pneumonia | – |

| 47–48A | 2014 | Mohr gazelle | Trauma | – |

| 49A | 2015 | Horse | Liver failure | – |

| 50–51A | 2015 | Thompson gazelle | Septicemia | – |

| 52A | 2015 | Watusi | Enteritis | – |

| 53A | 2015 | Gazelle | Pneumonia | – |

| 54A | 2015 | Yak | Pneumonia | – |

| 55A | 2015 | Goat | Trauma | – |

| 56A | 2015 | Goat | Pneumonia | – |

| 57–60A | 2015 | Rabbit | Pneumonia |

| Data | Years | Species | Causes of death | Lab. findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1B | 2004 | Lion | Neoplasia | Alveolar Carcinoma |

| 2B | 2004 | Opossum | Encephalitis | – |

| 3B | 2004 | Goat | Pneumonia | – |

| 4B | 2004 | Dromedary | Enteritis | – |

| 5B | 2004 | Antelope | Blood poisoning | – |

| 6B | 2004 | Goat | Pneumonia | – |

| 7B | 2004 | Antelope | Pneumonia | – |

| 8B | 2004 | Yak | Clostridiosis | Clostridium spp. E.coli |

| 9B | 2004 | Ilama | Thoracic Trauma | – |

| 10B | 2004 | Nilgai | Clostridiosis | Clostridium perfringens |

| 11B | 2004 | Watusi | Chronic gastritis and entheritis | – |

| 12B | 2004 | Dromedary | Septic granuloma | Trichostrongylus spp. Protostrongylus spp. Nematodirus spp. |

| 13B | 2004 | Blesbuck | Pneumonia and pleuritis | Trichostrongylus spp. Protostrongylus spp. Ostertagia spp. |

| 14B | 2004 | Eland | Blood poisoning | – |

| 15B | 2004 | Eland | Pneumonia | E.coli |

| 16B | 2004 | Lion | Paraplegia (euthanasia) | – |

| 17B | 2004 | Blesbuck | Pneumonia and pleuritis | – |

| 18B | 2004 | Goat | Pneumonia | |

| 19B | 2004 | Lion | Aspiration pneumonia | – |

| 20B | 2005 | Giraffe | Heart attack | – |

| 21B | 2005 | Goat | Not determined | – |

| 22B | 2005 | Goat | Not determined | – |

| 23B | 2005 | White Lion | Aspiration pneumonia | – |

| 24B | 2005 | Lion | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 25B | 2005 | Lion | Mesothelioma | – |

| 26B | 2005 | White lion | Pneumonia | – |

| 27B | 2005 | Antelope | Severe pneumonia | – |

| 28B | 2005 | Tiger | Peritonitis | – |

| 29B | 2005 | Barbary sheep | Trauma | – |

| 30B | 2006 | Tiger | Enteritis | – |

| 31B | 2006 | Racoon | Trauma (thoracic hemorrage) | – |

| 32B | 2006 | Tiger | Not determined | – |

| 33B | 2006 | White lion | Inborn malformation | – |

| 34B | 2006 | Mouflon | Trauma | – |

| 35B | 2006 | Lion | Maxillary hypoplasia | – |

| 36B | 2006 | White Lion | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 37B | 2006 | White Lion | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 38B | 2006 | White Lion | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 39B | 2006 | White Lion | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 40B | 2006 | Waterbuck | Politrauma | – |

| 41B | 2006 | Goat | Pneumonia | – |

| 42B | 2006 | Waterbuck | Foreign body (peritonitis) | – |

| 43B | 2006 | Siberian Tiger | Severe pneumonia | – |

| 44B | 2006 | Gemsbuck (Oryx) | Pneumonia | – |

| 45B | 2006 | Waterbuck | Severe pneumonia | – |

| 46B | 2006 | Eland | Trauma | – |

| 47B | 2006 | White lion | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 48B | 2006 | White lion | Severe pneumonia | – |

| 49B | 2007 | Siberian Tiger | Severe pneumonia | – |

| 50B | 2007 | Eland | Severe pneumonia | – |

| 51B | 2007 | Racoon | Poisoning | – |

| 52B | 2007 | Hippopotamus | Trauma | – |

| 53B | 2007 | Wildebeest | Trauma | – |

| 54B | 2007 | Dromedary | Abortion | E.coli |

| 55B | 2007 | Gemsbuck (Oryx) | Trauma | – |

| 56B | 2007 | Lion | Pneumonia | – |

| 57B | 2007 | Tiger | Cranial trauma | – |

| 58B | 2007 | Tiger | Suffocation | – |

| 59B | 2007 | Tiger | Severe pneumonia | – |

| 60B | 2007 | Siberian Tiger | Severe rhinitis and pneumonia | – |

| 61B | 2007 | Gemsbuck (Oryx) | Infection | Moraxella spp. |

| 62B | 2007 | Hippopotamus | Trauma | – |

| 63B | 2007 | Buffalo | Blood poisoning | – |

| 64B | 2008 | Lion | Trauma | – |

| 65B | 2008 | Deer | Trauma | – |

| 66B | 2008 | Tiger | Internal hemmorage | – |

| 67B | 2008 | Baboon hamadryad | Hypothermia | – |

| 68B | 2008 | Buffalo | Septicemia | – |

| 69B | 2008 | White lion | Pneumonia | – |

| 70B | 2008 | Waterbuck | Hypothermia | – |

| 71B | 2008 | Gemsbuck (Oryx) | Septicemia | – |

| 72 | 2008 | White Lion | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 73B | 2008 | White Lion | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 74B | 2008 | White Lion | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 75B | 2008 | Eland | Pneumonia | – |

| 76B | 2008 | Barbary sheep | Trauma | – |

| 77B | 2008 | Lion | Aspiration pneumonia | – |

| 78B | 2008 | Lion | Aspiration pneumonia | – |

| 79B | 2008 | Goat | Pneumonia | – |

| 80B | 2008 | Patagonian hare | Enteritis | – |

| 81B | 2008 | Lion | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 82B | 2008 | Lion | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 83B | 2008 | Lion | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 84B | 2008 | Eland | Severe septicemia | – |

| 85B | 2008 | Gemsbuck (Oryx) | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 86B | 2009 | Eland | Abdominal trauma | – |

| 87B | 2009 | Waterbuck | Pneumonia | E.coli |

| 88B | 2009 | Waterbuck | Trauma | – |

| 89B | 2009 | Waterbuck | Enteritis | E.coli |

| 90B | 2009 | Goat | Lymphoadenitis | – |

| 91B | 2009 | Goat | Enteritis and pneumonia | Staphylococcus xylosus Streptococcus bovis E.coli C.perfringens |

| 92B | 2009 | Goat | Enteritis | – |

| 93B | 2009 | Waterbuck | Peritonitis | – |

| 94B | 2009 | Waterbuck | Trauma | – |

| 95B | 2009 | Waterbuck | Metritis | E.coli Streptococcus bovis |

| 96B | 2009 | Tiger | Pulmonary abscess | – |

| 97B | 2009 | Tiger | Chronic nephritis | – |

| 98B | 2009 | Barbary sheep | Enteritis | Salmonella venezuelana |

| 99B | 2009 | Goat | Pneumonia | – |

| 100B | 2009 | Hippopotamus | Trauma | – |

| 101B | 2009 | Barbary sheep | Septicemia | – |

| 102B | 2009 | Barbary sheep | Enteritis | – |

| 103B | 2009 | Tibetan Goat | Enteritis | – |

| 104B | 2009 | Barbary sheep | Enteritis | – |

| 105B | 2009 | Barbary sheep | Enteritis | – |

| 106B | 2009 | Ilama | Enteritis | E.coli |

| 107B | 2009 | Dromedary | Abortion | – |

| 108B | 2009 | Lion | Neonatal mortality | |

| 109B | 2009 | Barbary sheep | Deterioration | – |

| 110B | 2009 | White lion | Inborn disease (macroglossia) | – |

| 111B | 2009 | Barbary sheep calf | Enteritis and pneumonia | – |

| 112B | 2009 | Barbary sheep | Pneumonia | – |

| 113B | 2009 | Barbary sheep | Enteritis | – |

| 114B | 2009 | Goat | Pneumonia | – |

| 115B | 2009 | White donkey | Colic | – |

| 116B | 2009 | Wildebeest | Hemorragic peritonitis | – |

| 117B | 2009 | Cameroon Goat | Abortion | – |

| 118B | 2010 | Watusi | Pneumonia | – |

| 119B | 2010 | Siberian tiger | Trauma | Diaphragmatic hernia |

| 120B | 2010 | Waterbuck | Pneumonia | – |

| 121B | 2010 | Goat | Pulmonary congestion | – |

| 122B | 2010 | Goat | Pulmonary congestion | – |

| 123B | 2010 | Gemsbuck (Oryx) | Anesthesia | – |

| 124B | 2010 | Sheep | Pulmonary congestion | – |

| 125B | 2010 | Goat | Pericardial effusion | – |

| 126B | 2010 | Gemsbuck (Oryx) | Parasitic hepatitis and pneumonia | – |

| 127B | 2010 | Waterbuck calf | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 128B | 2010 | Barbary sheep | Trauma | – |

| 129B | 2010 | Siberian tiger | Fallot pentalogy | – |

| 130B | 2010 | Antelope | Hepatitis | – |

| 131B | 2010 | Gemsbuck (Oryx) | Euthanasia | Septicemia |

| 132B | 2010 | Waterbuck | Trauma | – |

| 133B | 2010 | Waterbuck | Septicemia | – |

| 134B | 2010 | Waterbuck | Septicemia | – |

| 135B | 2010 | Tibetan goat | Pericardial effusion | – |

| 136B | 2011 | Siberian tiger | Euthanasia | – |

| 137B | 2011 | Wildebeest calf | Mesenteric hemorrage | – |

| 138B | 2011 | Dromedary | Neonatal mortality | – |

| 139B | 2011 | Siberian tiger | Trauma | – |

| 140B | 2011 | Eland | Septicemia | – |

| 141B | 2011 | Gesmbuck | Trauma and septicemia | – |

| 142B | 2011 | Antelope | Not determined | – |

| 143B | 2011 | Gemsbuck | Pneumonia | – |

| 144B | 2011 | Siberian tiger | Abortion and septicemia | – |

| 145B | 2011 | Dromedary | Pulmonary congestion and septicemia | – |

| 146B | 2011 | Eland | Gastritis | – |

| 147B | 2006 | Eland | Enteritis | – |

| 148B | 2011 | Goat | Pulmonary edema | – |

| 149B | 2011 | Tiger | Not determined | – |

| 150B | 2011 | Antelope | Mycosis | – |

| 151B | 2012 | Waterbuck | Septicemia | – |

| 152B | 2012 | Waterbuck | Trauma | – |

| 153B | 2012 | Giraffe | Septicemia | Achromobacter xylosoxidans Streptococcus bovis Stenotrophomonas maltophila |

| 154B | 2012 | Cow | Septicemia | – |

| 155B | 2012 | Bison | Enteritis | – |

| 156B | 2012 | Cameroon goat | Enteritis | – |

| 157B | 2012 | Goat | Trauma | – |

| 158B | 2012 | Gemsbuck | Degradation | – |

| 159B | 2012 | Goat | Pneumonia | – |

| 160B | 2012 | Cheetah | Neoplasia | Pancreatic neoplasia |

| 161B | 2013 | Cheetah | Interstitial nephritis | – |

| 162B | 2014 | Giraffe | Pericarditis | – |

| Register number | Years | Species | Causes of death | Lab. findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1C | 2004 | Barbary sheep | Pulmunary embolism | – |

| 2C | 2004 | Ferret | Cirrhosis | – |

| 3C | 2004 | Kangaroo | Pneumonia | – |

| 4C | 2004 | Tibetan goat | Pneumonia | – |

| 5C | 2004 | Cameroon sheep | Cysticercosis | Taenia saginata |

| 6C | 2004 | Tibetan goat | Pneumonia | – |

| 7C | 2004 | Barbary sheep calf | Trauma | – |

| 8C | 2004 | Ilama | Pneumonia and pericarditis | – |

| 9C | 2004 | Kangaroo | Pneumonia | – |

| 10C | 2004 | Kangaroo | Liver disease | – |

| 11C | 2004 | Kangaroo | Pneumonia | – |

| 12C | 2004 | Crab-eating macaque | Liver failure | – |

| 13C | 2004 | Fallow deer | Pneumonia | – |

| 14C | 2004 | Fallow deer | Pneumonia | – |

| 15C | 2004 | Girgentana goat | Pneumonia | – |

| 16C | 2004 | Blackbuck | Pneumonia | – |

| 17C | 2004 | Fallow deer calf | Trauma | – |

| 18C | 2004 | Raccoon | Trauma | – |

| 19C | 2004 | Barbary sheep | Pneumonia | – |

| 20C | 2004 | Blackbuck | Pneumonia | – |

| 21C | 2004 | Tibetan goat | Pneumonia | – |

| 22C | 2004 | Barbary sheep calf | Trauma | – |

| 23C | 2004 | Tibetan goat | Pulmonary edema | – |

| 24C | 2004 | Goat | Pneumonia | – |

| 25C | 2004 | Barbary sheep | Steatosis | – |

| 26C | 2004 | Chital | Pneumonia | – |

| 27C | 2004 | Barbary sheep calf | Hemorrhagic enteritis | – |

| 28–29C | 2004 | Barbary sheep | Pneumonia | – |

| 30–32C | 2004 | Kangaroo | Pulmonary edema | – |

| 33C | 2004 | Fallow deer | Predation | – |

| 34C | 2004 | Angora Goat | Septicemia | – |

| 35C | 2004 | Blackbuck | Pneumonia | – |

| 36C | 2004 | Barbary sheep calf | Pneumonia | – |

| 37–39C | 2004 | Tibetan goat | Pneumonia | – |

| 40C | 2005 | Wallaby | Pulmonary edema | – |

| 41C | 2005 | Wallaby | Septicemia | – |

| 42C | 2005 | Squirrel | Trauma | – |

| 43C | 2005 | Ferret | Trauma | – |

| 44C | 2005 | Prairie dog | Hepatic neoplasia | – |

| 45C | 2005 | Squirrel | Pneumonia | – |

| 46C | 2005 | Ferret | Hemorrhagic enteritis | – |

| 47C | 2005 | Antelope | Pneumonia | – |

| 48C | 2005 | Barbary sheep | Trauma | – |

| 49C | 2005 | Tibetan goat | Pneumonia and pleuritis | – |

| 50C | 2005 | Kangaroo | Pericardial effusion and septicemia | – |

| 51C | 2005 | Kangaroo | Steatosis | – |

| 52C | 2005 | Barbary sheep | Pneumonia | – |

| 53C | 2005 | Goat | Trauma | – |

| 54C | 2005 | Angora goat | Pericardial effusion | |

| 55C | 2005 | Fallow deer | Pneumonia | – |

| 56C | 2005 | Antelope | Peritonitis | – |

| 57C | 2005 | Dwarf goat | Trauma | – |

| 58C | 2005 | Deer | Pneumonia | – |

| 59C | 2006 | Blue monkey | Pulmonary emphysema | – |

| 60C | 2006 | Fox | Pneumonia | – |

Interesting considerations can be made, on the basis of the obtained results.

Depending on the type of zoo, the category of dead animals and causes of death were represented differently, probably due to the diverse management system of enclosures used.

Trauma can occur as a result of poor enclosure design or during capture and transport. Moreover, animals may also be injured in fights with conspecifics, particularly after introduction into a new social group, or during mating. In fact forty seven animals (16.7%) of the study died from trauma due to injuries by conspecifics or capture.

Zoo animals are protected from some health risks that are normally faced by wild animals, thanks to measures such as vaccination (Fernández-Bellon et al., 2017) and the provision of an adequate diet. At the same time, contracting an illness remains an inevitable part of zoo animal life. In fact, diseases may be spread to zoo animals through contact with conspecifics, free-ranging species, pests, such as rats and mice, keepers or visitors (Schaftenaar, 2002; Zhang et al., 2017). The study highlights that the main cause of death of captive mammals, was attributed to infectious disease (177 animals, 62.8%). Similar data were reported for each of the examined zoos and 71.7% of the examined animals which died due to infective agents were ruminants.

According to scientific literature; ruminants frequently die from infectious diseases, mostly related to their intestinal flora swing.

Links between diet and gastrointestinal problems have been reported (Zenker et al., 2009; Schilcher et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2013). Moreover, diet and lack of structured feed items can be associated with acidosis in ruminants (Gattiker et al., 2014).

Enteritis and other pathological conditions of the digestive system were not the only diseases to have been identified, pulmonary diseases were also present. In fact, in every zoo (as described in Tables 5, 6 and 7), pneumonia and other pulmonary diseases were very common.

Respiratory infections are multifactorial diseases (Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer, 2015). Climate change is likely to be one of the factors which could increase the occurrence, distribution and prevalence of infectious diseases of the lung (Mirsaeidi et al., 2016). This result also coincides with literature, in particular for livestock. Different factors could affect livestock diseases when influenced by climate changes, such as the virulence of the pathogen itself, presence of vectors (if any), farming practices and land use, zoological and environmental factors and the establishment of new microenvironments and microclimates. The interaction of these factors is an important consideration in forecasting how livestock diseases may be spread (Gale et al., 2009).

In this study we also considered the mortality rate for each year. These data confirm that, even if there are no trigger factors of an uncontrollable epidemic in a territory, a different animal species in different years may be more prone to death.

Moreover, as demonstrated in this study, and also reported in a previous paper (Scaglione et al., 2010), in white lion cubs an increased risk of inbreeding and genetic abnormalities can be a peculiar element in zoos that are involved in the breeding of rare or endangered species, when genetic diversity can be low in captive populations (Hosey, Melfi & Pankhurst, 2009).

In Zoo 2, out of 48 dead carnivores, 14 (29.2%) died from infectious diseases and 15 (31.2%) died from genetic diseases or malformations. These latest findings, due to inbreeding, arose in felines, and in particular in the cubs. As described in the introduction, the use of studbooks may limit inbreeding and the consequent genetic abnormalities occurring in zoo animals (Leipold, 1980).

In literature different studies have been conducted on animal necropsies and they normally focus on a single animal species (EAZWV, 2008; Joyce-Zuniga et al., 2014).

A holistic approach was carried out in 1983, by the San Diego Zoo and the Department of Pathology of Zoo Animals, which conducted a survey on zoo animal necropsies over a fourteen-year period (Griner, 1983). Necropsies of wildlife and zoo animals were performed, taking into account all the species and all the taxa. The veterinarians highlighted the importance of necropsies and collection of data.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this research has been carried out to highlight how conservation, histology and pathology are:

-

all connected through individual animals;

-

extremely important to maintain populations of rare and endangered species and to learn more about their morphological and physiological conditions;

-

useful to control diseases, parasites and illnesses which could have a great impact on those captive species. The necropsy room could represent an observatory on Zoo animal health. Finally, this study underlines the importance of:

-

a close collaboration between veterinarians, zoo biologists and veterinary pathologists;

-

necropsy findings which can help determine how to support wild animal populations.