The Book of Sarah is her own story. It's the story of a troubled young woman coming to terms with her cultural inheritance, with her emotional baggage, with desire, with wanting to be loved, with motherhood, and with her struggle to find autonomy when for long periods she didn't really know who she was.

It is a remarkably candid piece of work, but also remarkably sophisticated in the way it plays off word and image, makes them echo and harmonise and sometimes clash. It's a vision of the world as seen through faces and buildings and everyday objects and at the same time the "everydayness" of it floats on a sea of deep interiority.

Here she talks to Graphic Content about religion, feminism, the battle for self and why apples are difficult to draw:

Sarah, tell us about the origins of The Book of Sarah?

The Book of Sarah began when I was student at The Slade School of Art over 20 years ago.

I found myself overwhelmed and lost in the art studios during my first year, and I had no idea what art to make. I found myself going backwards, and inwards and this led me to start to draw my life from childhood photos.

The Book of Sarah was also an attempt to reconcile my worlds and experiences. I was a traditionally brought up Jewish woman in an art school in London. I had spent a year in Israel studying the Jewish texts, and instead of feeling I had found a Jewish home after my Church of England school, I rarely found myself, as a woman, reflected in the biblical stories I read. Nor could I find myself in any of the rabbinic commentaries that we studied.

The Book of Sarah was a creative response. I made a small printed book with text in it, a Book of Sarah, that was also known as The Hampstead Bible.

Even then, art was a way of reconciling myself, of drawing a place where I could be, and live, as myself.

How did it develop? When did you find that rhythm of word and image? Was there anything you had read that served as a model for your approach?

I have been inspired by Life? Or Theatre? by Charlotte Salomon. Salomon was a Jewish artist, born in Berlin in 1917, who moved to France to escape the war. Tragically, she was sent to Auschwitz, where she died in 1943. Life? or Theatre? is a three-colour opera that is over 800 pages long; the first autobiographical graphic novel. I love Salomon's way of drawing her life, and how the pages vary from careful renditions of homes and countryside to much looser pages of text and repeated images.

I knew I also wanted to write and draw my life. At art school, there were others working in text, but they didn't take as much care over drawing images as I did. In addition, my constant references to being Jewish, whilst making this vulnerable work, left me feeling very isolated. Salomon was an artist with whom I felt I had much in common and from whom I could draw strength.

It's a very open, candid take on your own life and thought. How easy was it to put it down on the page?

I felt this very strong need to tell my story. It was almost an unbearable need. And I only felt a release when the words that circled my head were finally written down. Sometimes these phrases were like buzzing bees in my consciousness. Now they are on the page and it is such a relief to see and hear my thoughts and feelings in the world.

I also knew that if I made art then people would stop, see and listen. Perhaps I now understand my need to be heard was exactly what I felt my parents and family never did. They couldn't hear my voice above their own needs and anxieties, or the background noise of the family home. But on the page I could write and draw as I wanted. I could be heard and hear myself.

I know that no matter how much we reveal about ourselves it will always resonate with others. That's the magic of autobiography. Our deep truths, worst feelings, biggest regrets all have elements of the universal, and reflect how our lives are part of the wider human experience.

Faith can be a belief system, an identity, a source of comfort or a source of disaffection. What is your own relationship with Jewishness (nice easy question there? You can probably wrap that up in about 20 words, right?)

I am no longer obliged to be a religious Jew, with strict laws and behavioural expectations. Instead, I feel very happy with a life and identity that reflects how I enjoy the cultural heritage of being Jewish. Harry and I go to a Reform synagogue and attend communal meals there. We both like the songs and music, and the creative ways that festivals are celebrated in that synagogue.

I also have a very intellectual relationship with being Jewish – my own academic work and writing reflects my love of Jewish feminist theology, and feminist Judaism. I have been transformed by the writings of Alicia Ostriker, Esther Broner and Laura Levitt. I am so happy to have found this tribe of Jewish women who are feminists and intellectuals, who are developing and creatively engaging with their own Jewish intellectual and cultural history. I celebrate their work and books in my graphic novel, as I draw their front covers. Even though these women live miles away, their books help me feel part of a community and conversation.

You talk near the beginning of using your diary as a place to store all your "thoughts, desires and dark secrets" when you were a child. What was art and drawing for at that age? Was there any crossover?

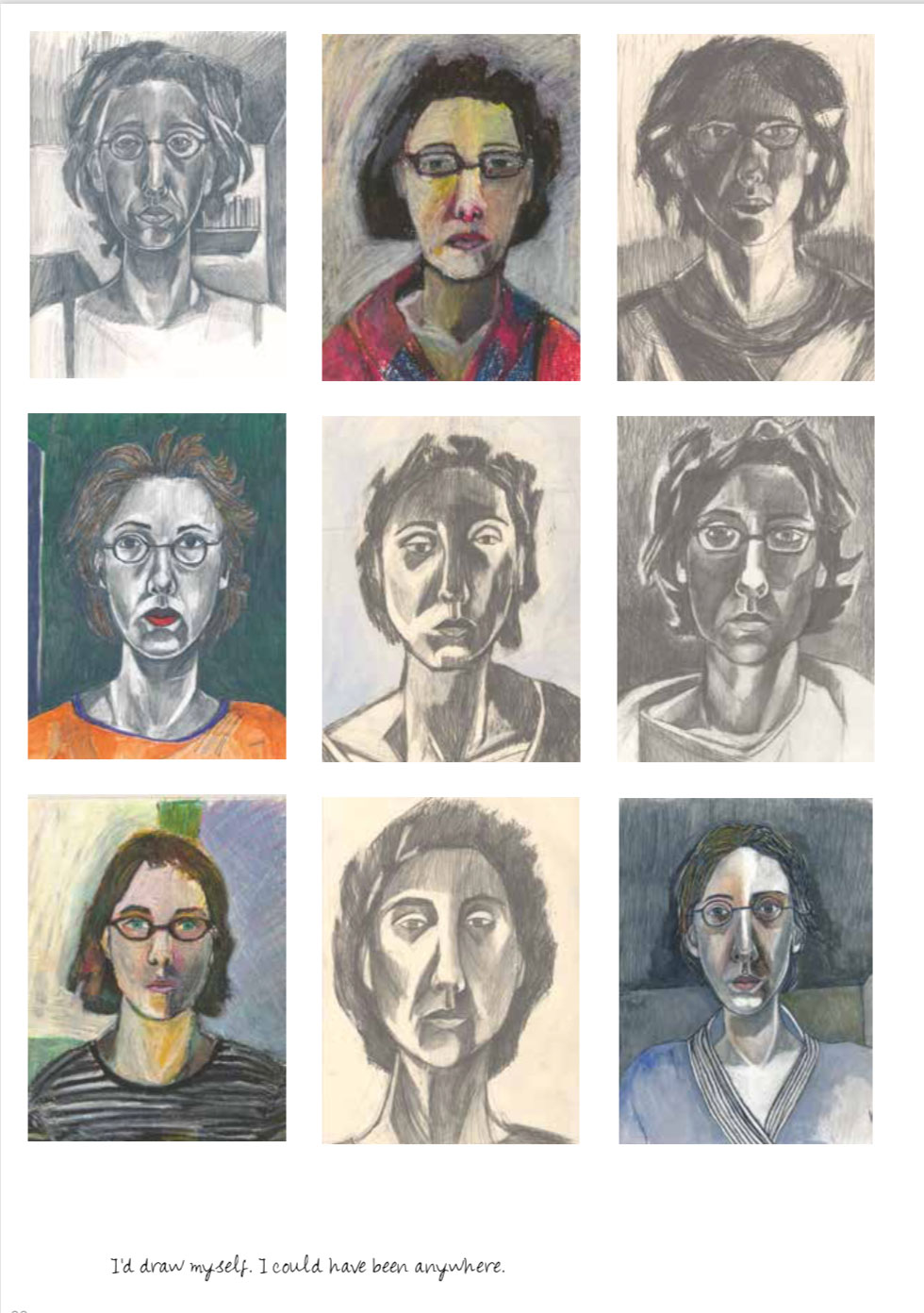

Diary writing was so important to me at school. I do recall making some autobiographical text/image art at A-level, but my art teacher was a bit freaked out and recommended that I did not exhibit them. I also made a significant self-portrait when I was 15. Everyone else in my class made these jolly little works, and they all looked so nice and wholesome and pretty. I drew myself with a sad face and tired eyes, taking care over each eyelash, each curl of unruly hair. I was looking at myself with such a forensic gaze, trying to capture my feelings and the reality of my world. Even though that image did not use text, it was my attempt at making a drawing tell a story and explain how it felt to be me.

You never name your unhappiness, never label it. Was it ultimately unnameable?

I think the depression – that might be the best word I can think of – was mostly based on a feeling of powerlessness. I felt to be loved I couldn't be myself and I never believed that my own desires and ambitions were legitimate. So, over the years, I learnt to ignore my feelings and I did things I didn't want to do, and, I said no to things I wanted to do. In the end I created a life that I didn't really want to live in. Eventually this became so intolerable that I went and got the help I needed to change my behaviour and beliefs. Now I have learnt I can say no to other people, and I can say what I want. I could withstand other people's negative responses to me, as well. These days, my own thoughts and dreams are precious to me, and I love to ask myself what I want to do and make, and I delight in my own autonomy.

I also recognise that in the culture I grew up in, everything centred around men and their success. Women were expected to fit around the men, to curtail their dreams. I don't do that now, but it was a huge cloud over me for much of my early years. I would have these deep drives and ambitions. I wanted to be standing up and talking about my ideas, in synagogues, or other centres of learning. I wanted my books on bookshelves, I wanted to be known for my own achievements. But it was only the men who seemed to do that with ease and be treated with respect for their accomplishments.

You return again and again to faces and places in your drawings. What is the pull of people and buildings for you as an artist?

I love to draw. I especially love to draw really carefully over time – the feeling of the pencil on paper, slowly, slowly building up form. I also love to use my eraser to remove marks and still leave a trace. Don't all our life experiences leave a trace on us, physically and mentally?

The pages of drawings of buildings were also about the time it took to draw every brick, every windowsill, every doorway. Sometimes my feelings were so strong I would cry as I drew and remembered what had happened there. But even though the story made me sad, I never stopped loving drawing.

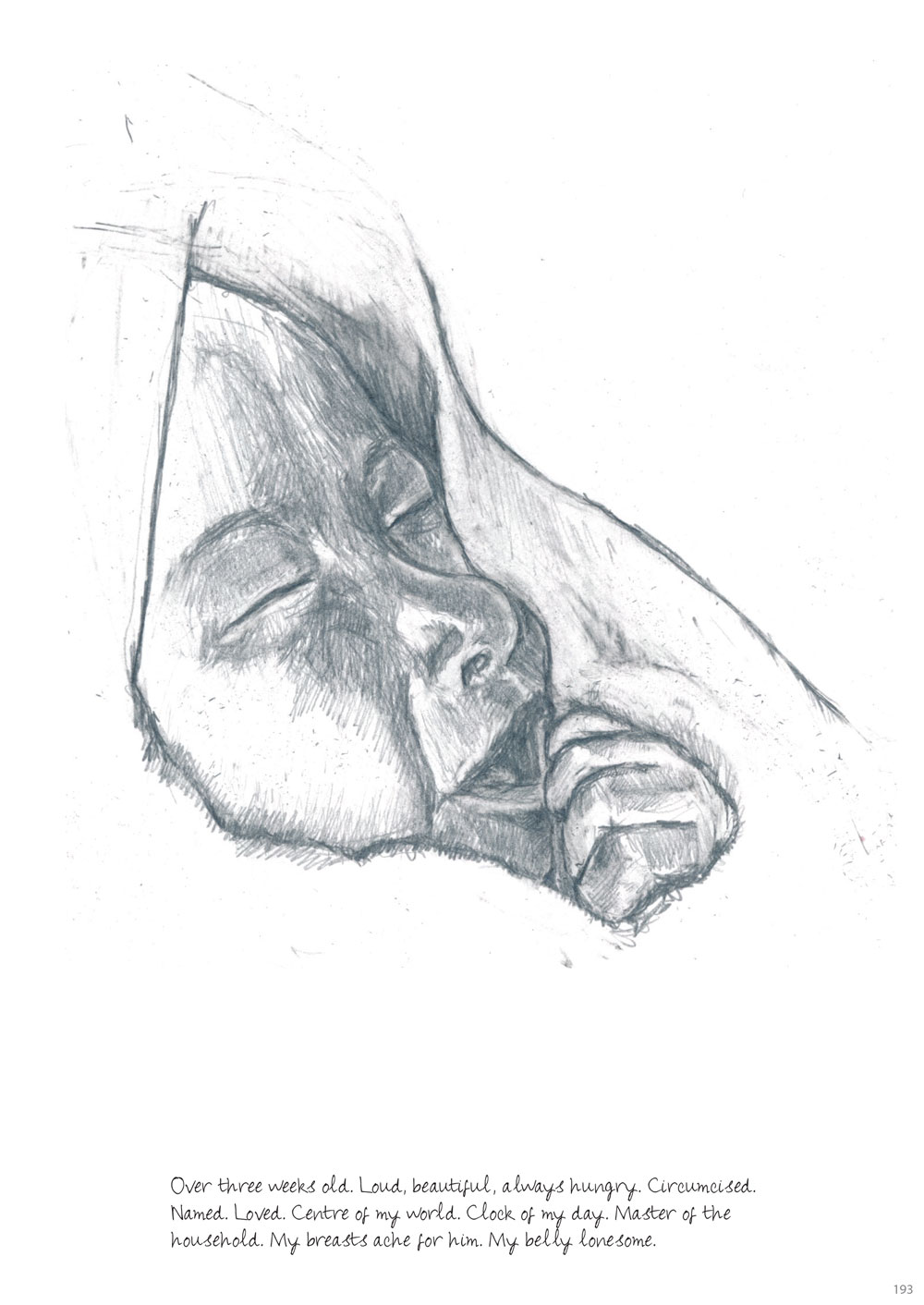

Reading your book was a reminder that parenthood is this constant swing between joy and fear.

I am so glad you said that. Yes, it is. I have also learnt to live with risk and uncertainty, so Harry can be comfortable with this feeling as well.

I love that drawing of a knife and my fear of "f*****-up motherhood".

When Harry was little, I suddenly became aware of danger everywhere, and, also, I felt I would be judged harshly as a mother if anything were to happen to him.

There are so many different objects in the book; from fruit to buses, telescopes to plastic cartons? Which one was the biggest bugger to draw?

The apples were tricky, making things round and reflecting light on any surface is hard. But that is also so exciting. I feel it is a constant question – can I really draw this? And the answer is always yes, yes, I can. Drawing is magical. A flat piece of paper becomes a world, or a thing; a space, place or object of memory.

What do you love most about the mixture of words and pictures? (Will you do more like this?)

I am not working on another graphic novel at the moment. Instead, my current project is editing my PhD, "Dressing Eve and Other Reparative Acts" to become a monograph published by Penn State University Press in their series, Dimyonot: Jews and the Cultural Imagination, edited by Samantha Baskind. I am so excited that my thoughts on feminism, art, biblical images and comics will be published in the future.

After that book I want to focus on making paintings. I want to make narrative paintings. I have seen so many paintings that inspire me, and I can't wait to have time to make paintings that are layered with stories, thoughts, feelings and people.

What do you most want to tell the world? Here's your chance.

Here are two thoughts I would love to share:

Firstly, all our stories matter and have importance. I use this phrase a great deal when I talk about autobiographical comics: "the superheroines and superheroes of everyday life". Nothing important or noteworthy has happened to me; I haven't changed the world, or made a lot of money, or held an important position. But I have struggled, and lost, won and survived, and that journey matters. My story matters, and so does yours.

And finally, there is this phrase: "You write the book you want to read". I was thrilled when my book was listed as a beach read for this summer on Bustle.com. Now, I, of all people, know The Book of Sarah is not a light reading. It's so thoroughly embedded in the grime of real life; you certainty couldn't call it escapist either. But it really made me laugh to see it as a recommended beach read for 2019 as there is page in The Book of Sarah where I describe my own depressing holiday reading material: "In Mexico, I relaxed by the beach in my designer sunglasses/ Reading books on trauma and bereavement." And now, here I am, someone else's wretched holiday reading.

I think that's pretty marvellous!